Under two visionary directors, New York’s WNYC became an incubator of pubmedia innovation

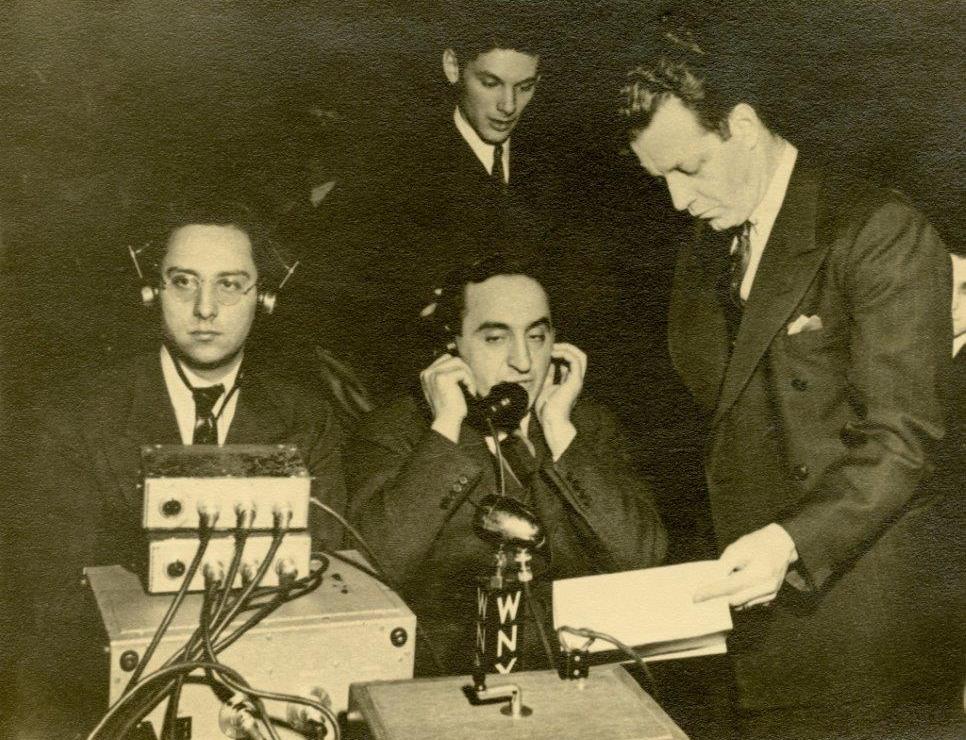

WNYC Archive Collections

WNYC director Morris Novik, on phone, with a news crew on an election night in 1941.

WNYC’s role in the history of public broadcasting has been somewhat unusual because our licensee was the City of New York, rather than a university or college. In that capacity, two of our directors, Seymour N. Siegel and Morris S. Novik, stand out as pioneers in the field who helped to shape and create models for public radio programming that continue today.

The public’s right to know, and taboo topics

It may come as a surprise to some, but Mayor La Guardia, that great champion of WNYC, had campaigned on a platform calling for the station’s demise in the name of taxpayer relief. Coming into office in 1934, he sent over the son of a political ally to shut it down. Fortunately, that young man, Seymour N. Siegel, was able to see through the 10-year-old station’s problems and flaws and helped to convince the Mayor it was worth saving. Siegel was made program director and embarked on a series of innovations.

Long before C-SPAN and Court TV, Siegel brought WNYC’s microphone into hearings for such events as the tragic fire aboard the luxury ship Morro Castle and a House Un-American Activities Committee looking into Nazi and other domestic right-wing subversion. The following year, Siegel had the station air a congressional inquiry into patent racketeering.

WNYC’s broadcast of these events confirmed for Siegel that radio could play a leading role in getting the audience into the legislative hearing room. Public response was positive and showed that listeners felt a sense of immediacy and participation when they heard these broadcasts.

Siegel’s next move was the judiciary. He sent WNYC’s microphone into Mott Street traffic court to focus on the police department’s highway-safety campaign. But New York’s judges were alarmed and moved swiftly to keep the radio from the state’s courtrooms. Siegel protested and wrote to The New York Times:

“The microphone enables us for the first time to bring educational work from the court room into the homes of great masses of people. It enables us thereby to displace suspicion, mistrust and the attendant evils of ignorance and misinformation. If public officials become conscious that masses of the citizenry are ‘listening in’ to their utterances and pronouncements, they will feel more keenly the necessity for being prepared for their daily tasks and would discharge them with greater efficiency.”

Public hearings and the courts were just the beginning for Siegel. In January 1938, he put WNYC’s microphones into the City Council chambers, and the public loved it. In letters to the station, listeners called the broadcasts instructive, entertaining, exciting and a step forward in good government. New Yorkers suddenly had a greater interest in civic affairs, and the Times called it “one of the best shows in the city, appealing in equal degree to the studio audience in City Hall and the radio audience over WNYC.” The experiment lasted two years before politics and the Democratic majority succeeded in ending the broadcasts.

In the arena of public health, Siegel responded to city health officials frustrated by the unwillingness of most media to discuss venereal disease. To combat widespread public ignorance on the topic, health officials and WNYC began a monthly broadcast about the symptoms, dangers and means of preventing syphilis and gonorrhea. Speaking before the Regional Conference on Social Hygiene in New York in early 1937, Siegel criticized commercial stations for being afraid to take on the problem. Summarizing the work of the city in this field, he said that the approach had been gradual and that public reaction was gratifying. “We have received thousands of letters regarding the programs. … There has not been one single unfavorable repercussion,” he reported. On March 13, 1938, Siegel invited the American Social Hygiene Association to take part in a combination drama and panel discussion about venereal disease on WNYC’s weekly hour-long Forum of the Air.

From July 1924 to January 1938, WNYC had been a part of the city’s Department of Bridges, Plant, and Structures — in other words, the public works department. But following through on the WNYC reform program sparked by Siegel, the La Guardia administration, with city council approval, created the Municipal Broadcasting System, a communications agency reporting directly to the mayor. Its first director was Morris S. Novik, a veteran of WEVD, under whom Siegel was program director before heading off to the Navy during World War II.

Public broadcasting and educating for democracy

During his time at WNYC, Morris S. Novik laid claim to coining the phrase “public broadcasting” and was active with the National Association of Educational Broadcasters, then the closest thing to a “public radio network.” In fact, at a special FCC committee hearing in October 1939, WNYC sought permission from the agency to allow the station to pick up via shortwave and rebroadcast selected programs for educational purposes from WRUL, Harvard University’s station. For Novik, as for Mayor La Guardia and NAEB members attending the hearing, shortwave links offered the greater potential of a pre-satellite public network without the prohibitively expensive land-line charges. Opposition to the FCC’s insistence of retransmission by wire only had been voiced by Mayor La Guardia a full year earlier at the opening of WNYC’s new state-of-the-art transmitter site. At that time, he said the commission rule prevented the formation of a “cultural network of non-commercial radio stations.”

The La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College/The City University of New York

Novik circa 1945

Novik’s leadership at WNYC played a vital role at the 1939–1940 World’s Fair as the station embarked on an extensive broadcast schedule from state-of-the-art studios in the City of New York Building in the shadow of the Trylon and Perisphere. At the time, Novik told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “WNYC is keeping constantly in mind that this World’s Fair will be more than just a show. Of course, we intend that many of our programs will be designed to bring out the serious side of the Fair, its cultural, social and educational significance.”

Another major Novik undertaking was the annual 11-day series of American Music Festival concerts at venues across the city in February 1940. The festival was a response to the dominant Eurocentric musical attitudes of the time. Reflecting on the festival’s birth, Novik said in an interview with the Times, “Our American music festival has a two-fold purpose. One purpose is to build the municipal radio station into an even greater force in the cultural life of the community, and the second is to promote the cause of good American music. American broadcasters have done a splendid job in developing an appreciation of classical music. Radio must do still another important job by focusing attention on American music, and by demonstrating that Americans have written good — even great — music.”

Understanding the power of radio and the advantages of FM, Novik wasted little time in applying to the FCC for a license on the new broadcast band in May 1940 and having Chief Engineer Isaac Brimberg make the technical preparations. In the meantime, he had to raise the necessary city funds for a transmitter, no small task in wartime New York City.

But thanks, in part, to the waiving of royalty payments by FM inventor and patent holder Maj. Edwin Armstrong, WNYC’s new “static-less” signal (W39NY) was on the air in March 1943, 1,000 watts at 43.9 FM. For a brief period, there were also WNYC shortwave broadcasts overseas using the call letters and transmitter of W2XVP out of the Municipal Building studios. Novik also helped Mayor La Guardia with the creation of a brief series of weekly underground broadcasts to the people of Italy over NBC’s shortwave outlets.

On the home front, there were many priorities — among them, fighting racism head-on with what Novik called “drama with a purpose.” This included radio plays about leading African-Americans who overcame racial bigotry and prejudice. Novik wrote, “They carried a message, and in an excitingly written and produced script these programs carried a punch that made the listener aware of certain inequalities that were common practice.”

And then there was the more subtle I’m Your Next Door Neighbor, a weekly Saturday-night series of dramas dealing with the adventures of a typical New York family. Novik described it this way: “The family happened to be a Negro family living in Harlem and the dramas each week dealt with the problems, business, and home life of this typical family unit. The cast included white and Negro actors playing their respective roles and often interchanging roles. Tolerance and prejudice were not the themes of the series, but during the course of normal events it was brought home to the listener that there were certain evils that perhaps he was not aware of previously.” This was just part of what Novik strongly believed was an essential mission for American radio, what he called “educating for democracy.”

The end of the La Guardia Administration also meant that Morris Novik’s time at WNYC was over. He went on to other broadcasting endeavors. President Truman appointed him a delegate to the 1952 UNESCO conference in Paris, and he was an advisor to the UNESCO London conference the following year. President Kennedy selected Novik to serve on the U.S. Advisory Commission on Information in 1962. He was reappointed to the commission by President Johnson. Until his death in 1993 , he remained close to WNYC.

Public radio network syndication is born at WNYC

In 1946 Seymour Siegel returned to civilian life, serving as acting director of WNYC until his formal appointment as director by Mayor William O’Dwyer in November 1947. He continued to build on the advances made under Novik’s tenure at WNYC, and as a veteran, he made sure there were programs to address the needs of those in transition to civilian life, the issues of the postwar economy, and the hopes everyone had for the United Nations. These broadcasts included Johnny Came Home, a drama series about the issues facing returning vets, and Economics of Peace, a series of roundtable discussions from New York University, which were followed by panel talks from the University of Chicago and Northwestern University. The programs ran into the 1950s and were complemented with lectures from the Cooper Union and The New York Academy of Medicine.

Though it may not seem like a big deal now, in April 1946, WNYC carried the first and complete sessions of the United Nations Security Council and soon after included General Assembly and other sessions. It was the only New York City station to do so at a time when expectations for the world organization were high.

Though it may not seem like a big deal now, in April 1946, WNYC carried the first and complete sessions of the United Nations Security Council and soon after included General Assembly and other sessions. It was the only New York City station to do so at a time when expectations for the world organization were high.

Siegel started the WNYC film unit in 1949, which became the foundation for the world’s first noncommercial municipal television station, WUHF — later WNYC-TV, Channel 31. He also continued the American Music Festival series, and by the early 1950s, there were annual book, art and Shakespeare festival program series as well. Cultural and music criticism and commentary were kept current with a roster including Gilbert Seldes, David Randolph, Edward Tatnall Canby, Walter Stegman, Robert C. Weinberg, and Alan Wagner.

Early in 1948, the NAEB was “making tentative plans looking toward the eventual establishment of an FM network of noncommercial and educational stations.” Siegel, a major player in the group, said a public network of this kind would benefit individual stations through the exchange of a variety of public service programming. Siegel emphasized that the network’s evolution would be a gradual process extending over a period. Yet, by June 1950, the network had nearly 100 stations and was providing a program service of some nine hours a week, distributed on tape to 35 of those stations through WNYC.

Being the distribution arm for the fledgling public radio network was more than WNYC could handle at the time, and the operations moved to the Division of Communications at the University of Illinois. Siegel continued to be active with the NAEB, serving as its President from 1950–52.

Sy Siegel gets around

Siegel was also involved with international broadcasting organizations and served as director of New York City’s Civil Defense Communications. Perhaps his highest honor was as a member of President Johnson’s broadcasters advisory council. Johnson specifically credited Siegel at the signing of the Public Broadcasting Act in 1967.

Through the 1950s and ’60s, Siegel continued WNYC’s efforts at playing the best in classical music, as well as airing The New York Herald Tribune Book and Author Luncheon, guest talks from the Overseas Press Club and Campus Press Conference roundtables. Always one to stay on top of current events, Siegel brought the issues and turmoil of the ’60s to WNYC’s airwaves with the programs City Close-Up, New York Tomorrow, Community Action and Black Man in America.

With the 1970s came severe budget cuts to most city agencies, and the Municipal Broadcasting System was no exception. On May 5, 1971, two days after the premiere of All Things Considered, Siegel was facing a 30 percent staff reduction and an operating budget cut of more than half ($1.2 million to $480,000). He handed in his resignation to Mayor Lindsay.

After 37 years at WNYC, Siegel said he was “terribly disappointed the budget makers hadn’t made WNYC a higher priority.” It was a harsh blow to Siegel, who had successfully countered hostility and indifference from earlier mayors, city comptrollers and a host of others through the decades. Their penny-wise and pound-foolish approach to WNYC was met with creativity and grace by a man who knew how to stretch a dollar and work the system for the benefit of WNYC’s listeners.

The Siegel/Novik tenure of radio activity covers nearly four decades before NPR’s first appearance on the air. In that time they helped to influence and set standards for broadcasting in the public interest. As stewards of a station serving the nation’s largest metropolitan area, their work and contributions are perhaps best summed up by the station’s ID, first used in 1938 and continuing with slight variations into the 1960s: “This program comes from WNYC, New York City’s own station, where seven-and-a-half million people, who have come from all parts of the world, are now living in peace and enjoying the benefits of democracy.”

Andy Lanset is founding director of the New York Public Radio Archives (WNYC/WQXR). He has worked in public broadcasting as a reporter, producer, engineer and archivist for the last 35 years.

This essay appears as part of Rewind: The Roots of Public Media, Current’s series of commentaries about the history of public media. The series is created in partnership with the Radio Preservation Task Force, an initiative of the Library of Congress. Josh Shepperd, assistant professor of media studies at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and national research director of the RPTF, is Faculty Curator of the Rewind series. Email: shepperd@cua.edu