Our public TV–watching parties continue

Last month, Current launched “Get With the Program,” a monthly series of interactive online screenings looking back at iconic and historically significant public TV shows. We’re holding these events as we observe the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Public Broadcasting Act. Using the OVEE platform, we’re showing excerpts from a variety of shows and interviewing experts and people involved with the programs. You can even join us and ask questions of the panelists.

Our next screening is about an artful, provocative PBS documentary that aired on the documentary series POV in 1991 — though it proved too hot to handle for some stations. The film, Tongues Untied, looks at the experience of being black and gay. Its blunt language and explicit imagery makes for a film that’s difficult to imagine airing on PBS today — or ever. How did Tongues Untied get to public television, and how did stations and the public react? Join us at 1 p.m. Eastern time Wednesday, June 28 to find out.

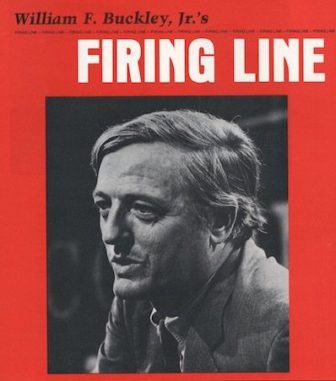

Here’s a taste of the conversations included in these screenings. The first one focused on Firing Line, the long-running public affairs show anchored by the renowned conservative William F. Buckley. I interviewed Heather Hendershot, an MIT professor and author of a book about the show, and Henry Cauthen, a former president of South Carolina ETV who helped bring Firing Line to public TV. In this excerpt from our conversation, Hendershot described how and why Newton Minow, then the chairman of PBS, intervened to save Firing Line from cancellation in the late 1970s.

Heather Hendershot: He noted that funding had been dropped for Firing Line, and he immediately jumped on that and said, “You cannot drop our flagship conservative programming.” He recognized there was a liberal slant to PBS and this show was really important for trying to balance out what we offer to viewers. And he immediately nipped that in the bud. … And he went to Walter Annenberg and asked him for money, and Annenberg gave the Corporation for Public Broadcasting millions of dollars, and a chunk of that went towards subsidizing Firing Line.

So it did continue on the air. It was never profitable in any way. And it’s worth emphasizing that. I guess that’s generally true of most PBS programming, with the exception of maybe Sesame Street having product tie-ins. Firing Line was never super highly rated, it never turned a lot of money over, and and Buckley had no problem with that. He was the biggest free-market capitalist around, and he was like, yeah, of course this show doesn’t make a profit. “You don’t expect the Catholic Church to make a profit,” he said at one point. … His point was that there are certain institutions that perform a public good, and it’s not about profit, and he felt that Firing Line was like that. … It was sort of niche programming that politically engaged liberals and conservatives would watch, but that wasn’t necessarily the mass audience that wanted to watch stuff like Gunsmoke or The Lucy Show on network TV.

So it did continue on the air. It was never profitable in any way. And it’s worth emphasizing that. I guess that’s generally true of most PBS programming, with the exception of maybe Sesame Street having product tie-ins. Firing Line was never super highly rated, it never turned a lot of money over, and and Buckley had no problem with that. He was the biggest free-market capitalist around, and he was like, yeah, of course this show doesn’t make a profit. “You don’t expect the Catholic Church to make a profit,” he said at one point. … His point was that there are certain institutions that perform a public good, and it’s not about profit, and he felt that Firing Line was like that. … It was sort of niche programming that politically engaged liberals and conservatives would watch, but that wasn’t necessarily the mass audience that wanted to watch stuff like Gunsmoke or The Lucy Show on network TV.

Mike Janssen, Current: Henry, do you think that today public TV needs a Firing Line for conservative balance? … What do you think about what’s on PBS today and how well-balanced it is?

Henry Cauthen: It’s a little better than it was in the early days, but it’s still very liberally oriented, at least in my view. And unfortunately, there no longer is a Firing Line on it. It needs another Firing Line. They will never get another Buckley, but they need to have a program that is in that spirit. …

Janssen: Why do we not have a Firing Line–type show today on public TV?

Hendershot: It’s a mix. Henry points to the fact there was only one Buckley, and it’s true. How do you do a new Firing Line without finding just the right charismatic, erudite kind of kind of figure?

But the other explanation for the lack of a Firing Line today has to do with just the nature of the media landscape and how everything is so niche. There’s a channel just for people who are into gardening. There’s a channel for people who are into pets. There is a channel for people who are into home improvement. And it’s the same thing with news and public affairs. There’s a place to go if you’re conservative, there’s a place to go if you’re liberal. And certainly a lot of talk radio is skewed one way or the other, mostly towards more conservative and right-wing programming.

So it’s harder to find a venue that functions as a kind of genuine public sphere of public comments — the old Habermas idea of people talking and open communication, and their ideas come into conflict and they try to reach a resolution — where’s that going to happen on TV where everything is so narrowly targeted and people are in echo chambers where they already see and consume programming that already fits their interests or their political backgrounds or needs or desires? That makes it very hard for a show to exist that is evenhanded debate between a conservative and a liberal just having a conversation. And so you end up with stuff like Crossfire, which is just people shouting at each other. And it’s very entertaining, but it’s like cockfighting or bear-baiting on some level. We can do a lot better on television and radio.

Cauthen: Clearly in broadcasting today, if you look at what’s on the air you can see that it’s very liberally oriented. … So the effort to get conservative programming on any broadcasting service has been one that we haven’t been terribly successful in.

But Heather has given a very good outline and feeling for what Firing Line was like and an understanding for what Bill Buckley was like. You’re not going to find another one. So it took a special person to get a conservative view on public broadcasting.

When we first started with public broadcasting with Bill Buckley, my relationship with him was totally professional. But over time we grew to be very good friends. He even wanted me to come on many trips, especially when [the program] went out of the country, and of course I did when I could. But Buckley was just a special person. I’m sure he vetted me very carefully before he came with South Carolina ETV. … I never found anybody that was more cordial and more interested in what you had to say and what you had to think about.

And what he did on the program to a lesser extent was what he did every day with friends. Anytime anybody came on Firing Line, they became a member of a small club of people that kept communicating with one another. Whether they were totally liberal or conservative, they always went away friends of Bill Buckley’s, and he to them. So it was a unique relationship. It wasn’t going to the studio and doing the program and leaving. That’s what guests usually did on most programs. But [on Firing Line] they usually stayed a long time and had additional conversations, and they would maybe iron out some of the arguments they’d had on the air. So it was interesting to watch that process.