Journalists don’t have to be sidelined from community involvement

Many matters of journalism ethics involve preventing bad practices such as plagiarism or ensuring good journalism with standards for accuracy. Guidelines for avoiding conflicting interests in community affairs are different, requiring journalists to weigh the relative importance of two good practices: journalistic independence and community involvement.

“It’s important for journalists to understand the community that we’re living in,” said Michael Arnold, director of content at Wisconsin Public Radio. “Sometimes it’s easy for journalists to seem detached.”

In interviews and an online questionnaire for the Editorial Integrity for Public Media Project, journalists in public broadcasting and other media segments agreed that maintaining their independence doesn’t require them to avoid such common community activities as worshipping, voting or coaching a children’s sports team. But journalists widely recognize that they start to risk potential conflicts when their involvement extends into leadership roles, fundraising and advocacy for social issues.

Assessments of where involvement crosses a line to create conflict seem to vary widely, depending on the situation and the priorities of the journalists involved.

“My views on these issues have become more nuanced over the years,” said Melanie Sill, VP for content at Southern California Public Radio. “The longer I’ve worked in journalism, the less these issues have seemed black-and-white.”

In survey responses and interviews, journalists and managers generally agreed that rules can’t govern the nuanced decisions journalists face in the gray areas. Good decisions in those areas rest in disclosure and discussion: Journalists need to disclose their activities, and they need to discuss potential conflicts and solutions with colleagues and supervisors.

Wisconsin Public Radio has frequent discussions among the whole staff, addressing case studies, so staff members in all departments can understand the importance of ethical issues and consider how they would act in particular situations. Credibility, Arnold said, is “the main reason why we talk about ethics all the time.”

Nearly 500 journalists and media managers responded to the online questionnaire “Journalism ethics questions on personal activities,” fielded Nov. 30 to Dec. 12.

Eighty percent or more of survey participants approved of journalists voting, worshipping in a local congregation, joining a neighborhood or homeowners’ association, or leading youth activities such as sports teams, Scouts or 4-H Clubs. But minority percentages of respondents approved of deeper commitments such as active involvement in faith-based organizations that take positions on social or political issues; leadership in fundraising, publicity or advocacy for children’s schools; or active roles in political parties or campaigns.

While it’s good for the community for someone to play those roles, they can create real or apparent conflicts for journalists who might cover news stories relating to those issues, organizations and people.

Many journalists have long expressed opinions privately, however careful they were in public statements. But social media present new challenges for journalists and their newsrooms. These platforms provide space for friends and family to express lots of opinions, but seemingly private statements can be seen by the public.

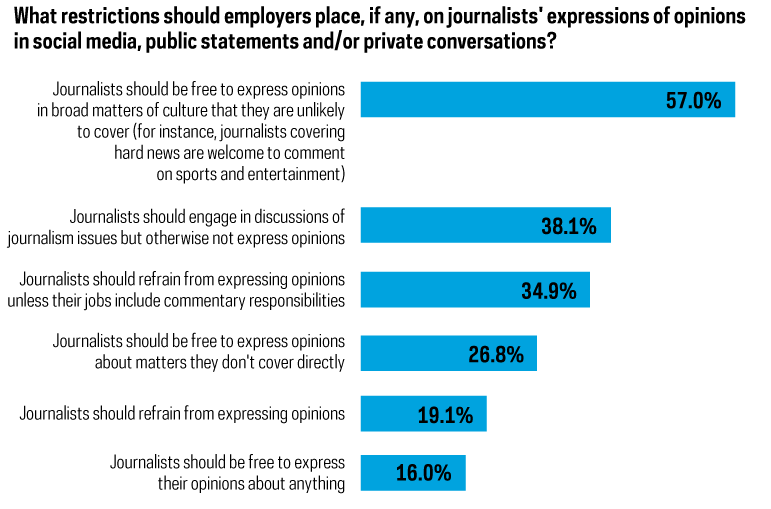

In the online questionnaire answered by 473 journalists and media managers, small clusters of respondents were at each end of the opinion spectrum when asked about guidelines for social media: Just 16 percent said journalists should be free to express opinions on anything in social media, and 19 percent said journalists should refrain from expressing any opinions. Larger numbers agreed with other statements between those extremes:

In the online questionnaire answered by 473 journalists and media managers, small clusters of respondents were at each end of the opinion spectrum when asked about guidelines for social media: Just 16 percent said journalists should be free to express opinions on anything in social media, and 19 percent said journalists should refrain from expressing any opinions. Larger numbers agreed with other statements between those extremes:

- Journalists should be free to express opinions on broad matters of culture that they are unlikely to cover. For example, journalists covering hard news are welcome to comment on sports and entertainment, according to 58 percent of survey participants.

- Journalists should engage in discussions of journalism issues but otherwise not express opinions (38 percent).

- Journalists should refrain from expressing opinions unless their jobs include commentary responsibilities (34 percent).

- Journalists should be free to express opinions about matters they don’t cover directly (27 percent).

- The percentages total more than 100 percent because respondents could check answers to more than one position.

The questionnaire was distributed by email and social media to public radio and television station managers and staffs, as well as to journalists in other fields. Just over half of those responding, 56 percent, work in public broadcasting. Nearly a quarter, 22.5 percent, were managers in non-journalism roles, while 36 percent were journalists in management roles. The range of opinions was similar, whether respondents worked for public or commercial broadcasting, print or digital media, and whether or not they worked in management.

Social media is “the hardest place” to guide staff members in expression of opinions, said Shawn McIntosh, deputy managing editor at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “It’s the public square where people talk.”

About once a month in the past year, McIntosh said, the Journal-Constitution reminded staff members in conversations or emails about the importance of refraining from expressing opinions, usually in social media. “The challenges are no different than they’ve always been, but the pressures on us to be transparent and devoted to independence are greater than ever.”

Joshua Adams, executive director of operations at Houston Public Media, said he issues similarly frequent reminders to his journalists to be careful about what they say, especially in social media. Advocacy for a position or cause is especially troublesome to Adams: “You impugn the reputation of Houston Public Media’s newsroom when you advocate for anything.”

Gavin Dahl, news director at KDNK community radio in Carbondale, Colo., is less concerned about staff members’ expressing opinions on social media. “I think there is a distinction between what they do on their own personal social media rather than one of our accounts. I personally think our audience could handle that.”

Dustin Dwyer, who reports on children and families in poverty for Michigan Radio, is more bothered by journalists’ unwillingness to express opinions than by the problems that might come with stating opinions. “We express opinions all the time in our reporting that go unchallenged in our newsrooms. We call it ‘news judgment,’ but it’s an opinion.” When reporters or news directors decide which stories to pursue and which to let go, he said, they are deciding, “This is what’s important, those other things aren’t. That has always been subjective and selective.”

Dwyer favors disclosure of opinions, rather than refraining from expressing them.

“Sometimes we value the appearance of impartiality over actual honesty about ourselves. I don’t think that’s ethical.”

Crystal Stryker, social media editor for WITF in Harrisburg, Pa., said she disclosed to her boss recently that she is a survivor of childhood sexual abuse and doesn’t feel comfortable dealing with stories that address that topic. “I know that if I’m emotional I’m not being objective,” Stryker said.

She also keeps her distance from coverage of stories relating to Penn State football because she is married to a former player for the Nittany Lions.

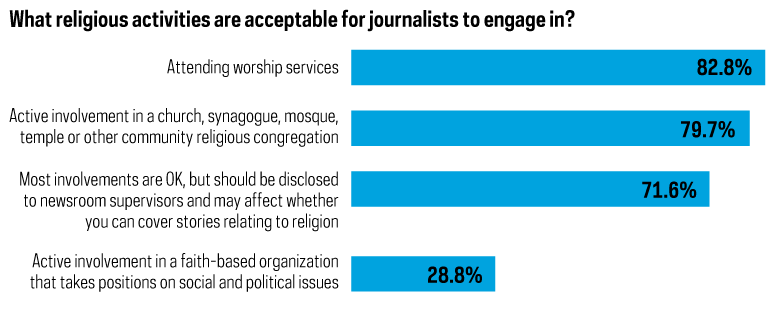

Answers to the online survey show that nuanced views of acceptable involvement extend across a range of activities, including religion, family life and community-based civic involvement.

In religious affairs, for instance, high percentages approve of attending worship services (83 percent) or active involvement in a church, synagogue, mosque, temple or other religious congregation (80 percent). But if a journalist wanted to be active in a faith-based organization that takes positions on social or political issues, only 29 percent approved.

In religious affairs, for instance, high percentages approve of attending worship services (83 percent) or active involvement in a church, synagogue, mosque, temple or other religious congregation (80 percent). But if a journalist wanted to be active in a faith-based organization that takes positions on social or political issues, only 29 percent approved.

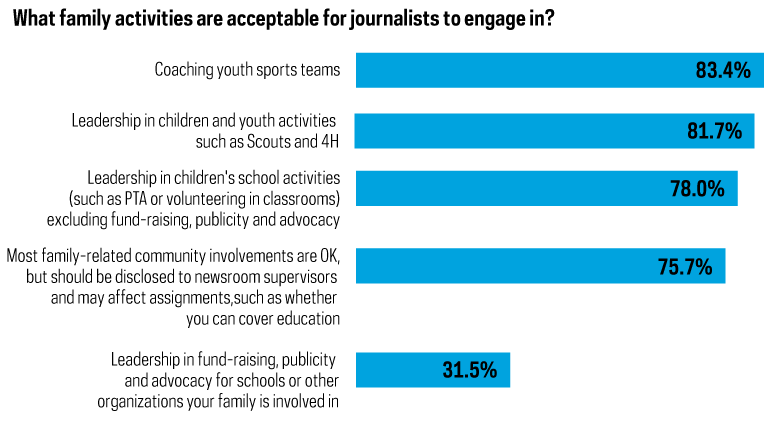

Similarly, large majorities approved of coaching youth sports (83 percent), leading children and youth activities such as Scouts and 4-H (82 percent), and leadership at a child’s school through a PTA or as a classroom volunteer (78 percent). That last option excluded fundraising and publicity from the approved school activities. If a parent wants to lead those efforts, or advocate for a school or other organization the family is involved in, only 32 percent of those surveyed thought that was acceptable.

Similarly, large majorities approved of coaching youth sports (83 percent), leading children and youth activities such as Scouts and 4-H (82 percent), and leadership at a child’s school through a PTA or as a classroom volunteer (78 percent). That last option excluded fundraising and publicity from the approved school activities. If a parent wants to lead those efforts, or advocate for a school or other organization the family is involved in, only 32 percent of those surveyed thought that was acceptable.

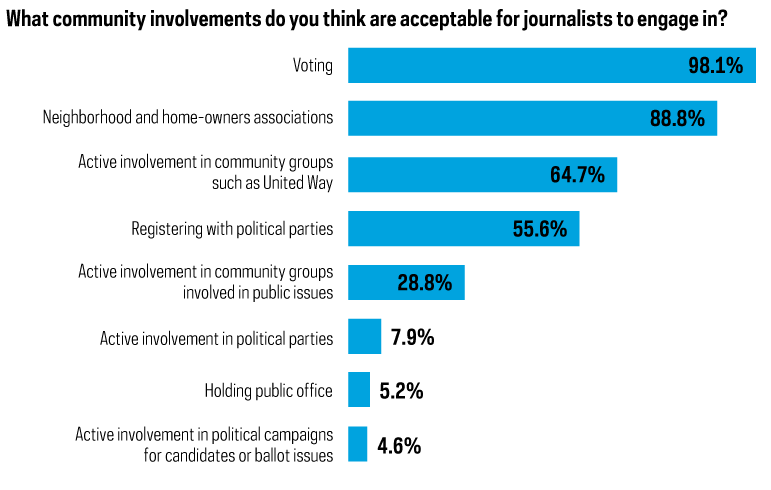

For community involvement, big majorities approved of voting (98 percent), membership in neighborhood or homeowners’ associations (89 percent) and active involvement in community groups such as United Way (65 percent). But only 29 percent approved of active involvement in community groups involved in public issues. Three types of community involvement didn’t get even 10 percent support in the survey: active involvement in political parties (8 percent), active involvement in political campaigns for candidates or ballot issues (5 percent), and holding public office (5 percent).

For community involvement, big majorities approved of voting (98 percent), membership in neighborhood or homeowners’ associations (89 percent) and active involvement in community groups such as United Way (65 percent). But only 29 percent approved of active involvement in community groups involved in public issues. Three types of community involvement didn’t get even 10 percent support in the survey: active involvement in political parties (8 percent), active involvement in political campaigns for candidates or ballot issues (5 percent), and holding public office (5 percent).

Responses to two questions on political affiliation indicated that survey participants were pretty evenly split. When asked whether they approved of journalists registering with political parties, 56 percent said “Yes.” Another 51 percent agreed that employers could bar journalists from donating money to political parties, candidates or causes.

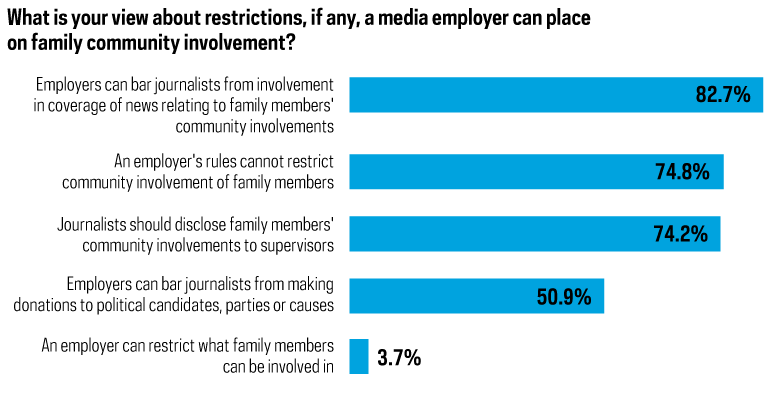

While family members’ community involvement can create uncomfortable situations in newsrooms, only 4 percent of those surveyed said employers should be able to restrict these activities. However, respondents strongly agreed (74 percent) that journalists should disclose relatives’ involvements to their supervisors and that supervisors can bar journalists from covering news where family members are involved (82 percent).

While family members’ community involvement can create uncomfortable situations in newsrooms, only 4 percent of those surveyed said employers should be able to restrict these activities. However, respondents strongly agreed (74 percent) that journalists should disclose relatives’ involvements to their supervisors and that supervisors can bar journalists from covering news where family members are involved (82 percent).

The survey and the interviews indicated that ethics rules cannot cover every possible conflict. “I approach all these situations as conversations,” Sill said. “The journalists themselves have the right instincts. You help them talk through making a decision.”

Such a conversation helped Durrie Bouscaren, who covers health and science for St. Louis Public Radio, decide against volunteering as a language tutor with a large immigration agency in the community. When a boss pointed out that she might have to deal with the agency in her reporting, Bouscaren agreed, “I wouldn’t feel comfortable using an organization that I volunteered for as a source.”

She ended up privately tutoring an immigrant who cleans the office, rather than volunteering through the agency. Rather than feeling limited by an arbitrary rule, Bouscaren appreciated the guidance.

“It’s a really hard thing for a newsroom to create hard-and-fast rules for,” Bouscaren said. “I think today we just have to be really transparent about what we do in the community. A lot of these things are so circumstantial. I think being involved in my community makes me a better reporter.”

Steve Buttry directs student media at Louisiana State University’s Manship School of Mass Communication. An award-winning editor who directed digital strategy at Digital First Media and community engagement at TBD.com, he has managed projects and provided training in newsroom innovation and journalism ethics.

This article continues our series published in collaboration with the Editorial Integrity Project to explore the challenges to public media journalism in a deeply polarized civil society. The project, funded by CPB, is an initiative of the Station Resource Group and the Affinity Group Coalition to develop shared principles that strengthen the trust and integrity that communities expect of local public media organizations.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred to Houston Public Media as Houston Public Radio.

[…] personally while still maintaining professional integrity and independence from outside influence. According to a Current article, a little over half of the journalists surveyed (57 percent) felt they should be free to express […]