Battered by political agendas, ‘The Wisconsin Idea’ lives on in public broadcasting

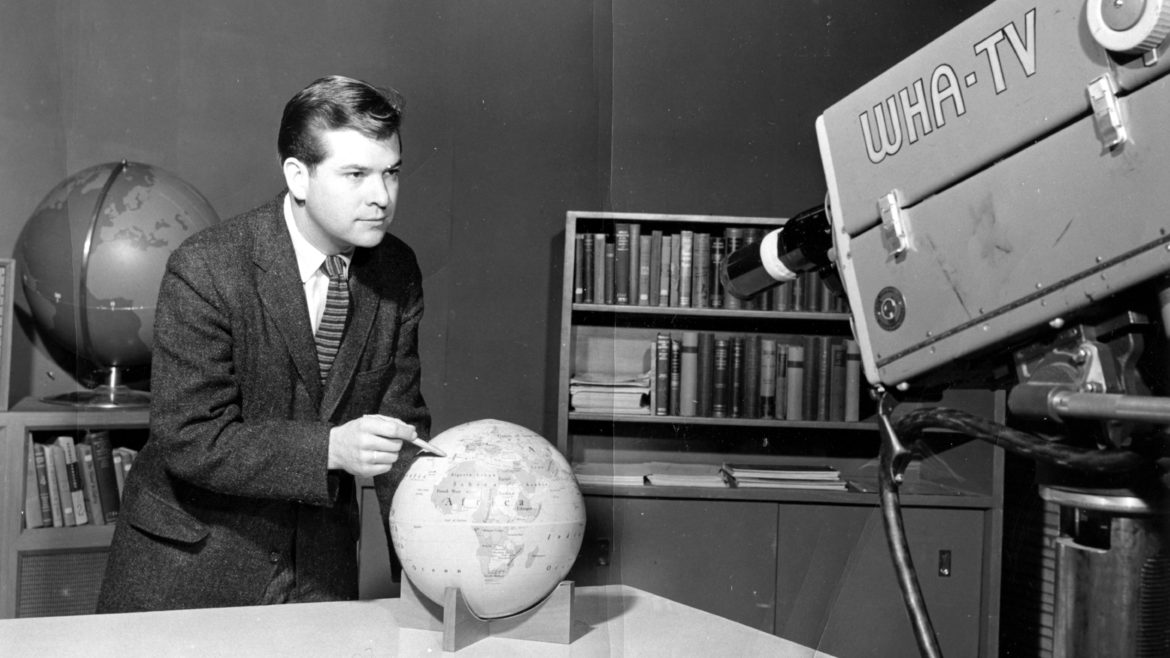

Geography professor Ric Johnson uses a desktop globe to explore The Big Wide World from the WHA-TV studio in 1958. (Photo: Wisconsin Public Television)

In 2015, Governor Scott Walker proposed removing “The Wisconsin Idea” from the University of Wisconsin’s mission statement. His small-government, low-tax, pro-business agenda was antithetical to the high-service, high-tax, anti-corporate priorities outlined in the 1912 book The Wisconsin Idea.

Public reaction convinced the governor to leave the language alone, but his proposed budget battered the Wisconsin Idea in practical ways. Budget cuts to the university and other public services offset tax incentives for business. Those cuts included eliminating state funding for the transmitters and delivery system that carry public radio and television programming throughout the state.

Few services exemplified the Wisconsin Idea more directly than the state-funded public broadcasting system, which first broadcast voice and music in 1917 when progressive ideas dominated the state’s politics. Nearly one hundred years later, the governor argued the listeners, viewers, businesses and foundations who valued the broadcast services, not state government, should fund them.

The governor’s recommendation reflected a very different mindset from the actions the Republican-controlled state legislature took in the spring of 1945. At that time, legislators voted to create a state-owned and -funded network of FM radio stations to relay to the entire state the programming of the University of Wisconsin’s WHA.

The governor’s recommendation reflected a very different mindset from the actions the Republican-controlled state legislature took in the spring of 1945. At that time, legislators voted to create a state-owned and -funded network of FM radio stations to relay to the entire state the programming of the University of Wisconsin’s WHA.

Even though instruction had never been the primary rationale for educational broadcasting in Wisconsin, the desire to deliver educational programs to rural schools helped motivate the decision to build a state network. However, the more fundamental motivator was the Wisconsin Idea, which said government should not leave services vital to the public interest solely to private, profit-driven corporations.

From its beginning in 1917, WHA sought to promote, in the words of University President Glenn Frank, “intelligence and moral responsibility” among broad audiences and to encourage understanding among diverse groups. Spreading the “university atmosphere” to the boundaries of the state, WHA respected facts and promoted rational discussion. President Frank recognized that radio did not address “students held prisoner in a classroom.” Radio listeners, he warned, were free to “turn from dull quality to interesting frivolity with a simple twist of the dial.” Radio, even educational radio, needed to entertain to instill values.

In 1945, the state board established to govern the “state stations” defined its mission as promoting “democratic ideals and principles” and engaging in the “sifting and winnowing” of the Wisconsin Idea.

The next year, in 1946, an earthquake named Joseph McCarthy shook Wisconsin politics. The returning war veteran defeated the state’s leading progressive, Sen. Robert La Follette, in the 1946 Republican primary. The progressive Republicans largely responsible for the Wisconsin Idea and the state’s commitment to educational radio lost control of their party and the state. Educational television arose in the midst of this new political reality.

When the Federal Communications Commission opened the airwaves for educational television in 1954, the University of Wisconsin jumped in quickly. With funding from the University and the Ford Foundation, WHA-TV was the third educational television station in the country to go on the air. It was clear, however, that a statewide network of stations, similar to the state radio network, would require a direct investment from the state government, just as it had for radio.

Recognizing the anti-government sentiments that had replaced the Wisconsin Idea as the dominant philosophy of the Republican party, advocates for the statewide television network emphasized service to schools and other narrowly instructional functions rather than “intelligence and moral responsibility” or “democratic ideals and principles.”

Even so, the idea of a state-funded educational television network was too much for many legislators, who punted the question to a statewide referendum. They asked voters in 1954, “Shall the State of Wisconsin provide a tax-supported statewide noncommercial educational television network?” A combination of commercial broadcasters and “patriotic” organizations campaigned against the referendum. Voters turned it down by a two-to-one margin.

Fourteen years later, in 1968, public television made a second attempt to fund a statewide network. This time they built their case totally on instructional television. Republican legislative leaders said the proposed network should carry “strictly construed instructional-credit course related programs” rather than “public service related” programming. However, it was the Democratic version of the network that actually passed. It did not prohibit “public service related” programming. It spoke vaguely of “educational opportunity for all citizens of the state,” while calling specifically for K-12 instruction, vocational and independent study and continuing professional education.

Ironically, Wisconsin’s decision in 1968 to build a state television network dedicated to instruction came just as the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 envisioned a national public television service built on diverse cultural and public affairs programming for the general public, consciously excluding credit courses and instructional programming. In many respects it echoed the Wisconsin Idea.

Operating independently of the state educational television network, WHA-TV, the University of Wisconsin’s television station in Madison, embraced the national philosophy of public broadcasting. In doing so, the station gave conservative legislators a concrete example of what they did not want. With funding from the Ford Foundation, WHA-TV created SIX30, a nightly news show produced by “the community of the disadvantaged,” the kind of program encouraged by the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television and the Public Broadcasting Act. SIX30 did not strive for objectivity. Rather, it sought to portray the community “as the disadvantaged perceived it, not as professional journalists reported it.”

Critics characterized the programmers as pro-Castro, pro–Black Panther revolutionaries, unclean, unkempt, anti-social dissidents, convicted criminals and radicals, “barely able to speak our language.” The university dropped SIX30 but retained “public” programming, much like that on PBS stations everywhere.

In 1989, independent WHA-TV and the state educational television network merged to create Wisconsin Public Television. The combined organization was overwhelmingly “public” in its programming but “instructional” in its justification for state support.

That contradiction exploded in Gov. Walker’s 2015 proposal to defund statewide delivery of public television and radio. His proposal left intact state support for public television’s nonbroadcast instructional activities. Listeners and viewers screamed in protest to the threats to their public radio and television services. Legislators heard them and decided they could not cut the service so many of their constituents valued.

However, the legislators were determined to cut something from the public broadcasting budget. They chose public television’s support for schools, the primary reason for building the state public television network in the first place! The legislators’ decision left only one rationale for public radio and television in Wisconsin. That rationale is the Wisconsin Idea of public service, the vision with which WHA began in 1917, nearly one hundred years ago.

Jack Mitchell was the first employee of NPR and the first producer of All Things Considered. He spent most of his career in Wisconsin, however, as director of Wisconsin Public Radio and, later, as Professor of Journalism at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of Listener Supported: The Culture and History of Public Radio (Praeger, 2005) and Wisconsin on the Air: 100 Years of Public Broadcasting in the State that Invented It (Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2016). This essay was based on the latter.

This commentary appears as part of Rewind: The Roots of Public Media, our series of historical essays about public media created in partnership with the Radio Preservation Task Force. The RPTF is an initiative of the Library of Congress. Josh Shepperd, assistant professor of media studies at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and national research director of the Radio Preservation Task Force, is Faculty Curator of the Rewind series. Email: shepperd@cua.edu