Early gay radio group donates collection to public broadcasting archives

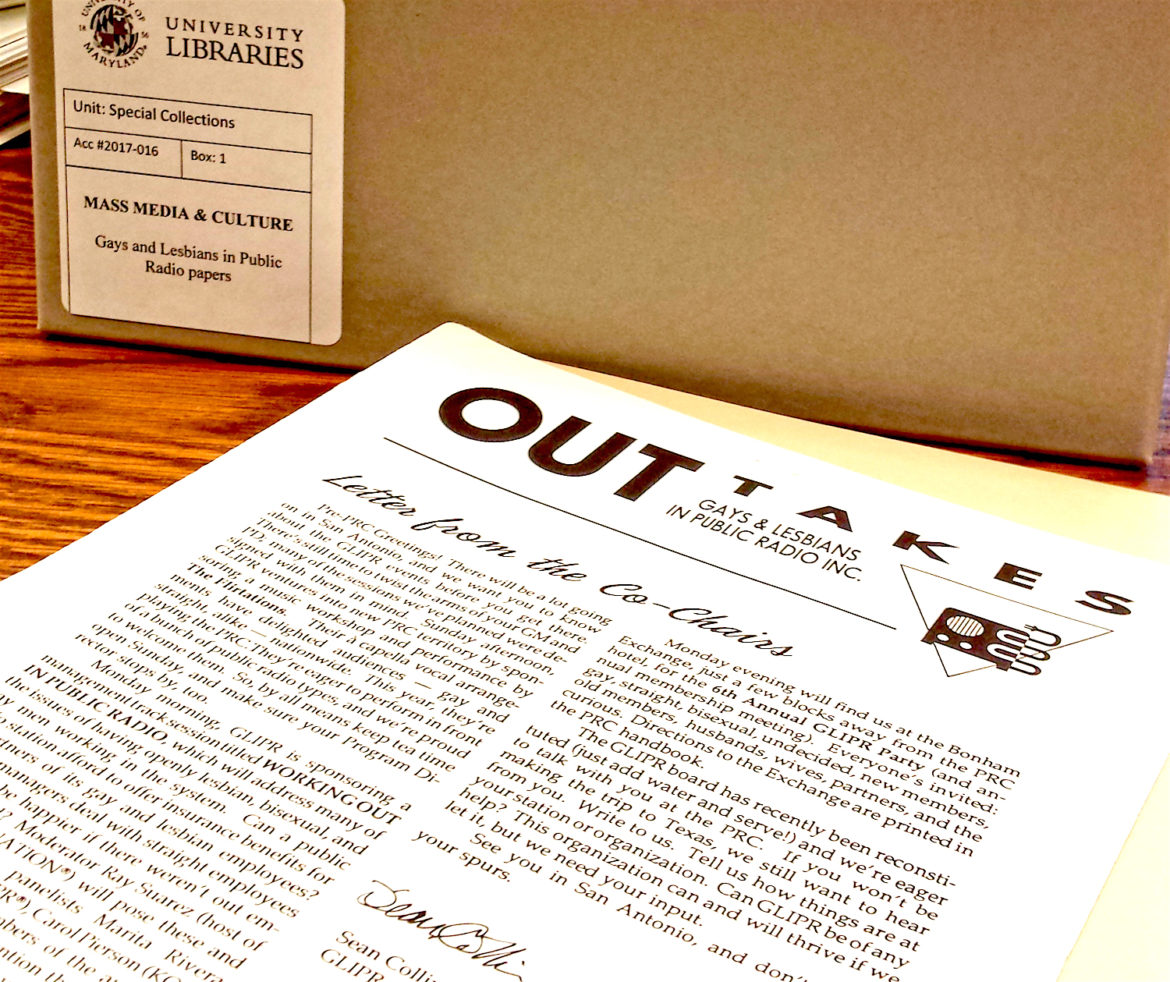

GLIPR's document collection, now at the University of Maryland, includes copies of its Outtakes newsletter. (Photo: Laura Schnitker)

GLIPR’s document collection, now at the University of Maryland, includes copies of its Outtakes newsletter. (Photo: Laura Schnitker)

The founding papers of Gays & Lesbians in Public Radio, an early gay-rights organization in public media, have been donated to the University of Maryland’s National Public Broadcasting Archives.

GLIPR, which was active from the late 1980s to the mid-’90s, was a small but dedicated group of public broadcasters who advocated for issues such as domestic-partner health benefits and editorial freedom to cover their community.

But perhaps more importantly, the organization offered gays in public radio camaraderie during a time when being openly gay could be both professionally and personally challenging.

“The first gatherings I attended in the early ’90s were at a time when there was still stigma attached to being gay,” said Sue Schardt, executive director of the Association of Independents in Radio. “The events GLIPR organized felt like a big deal. You were making a statement by attending.”

The small trove of the group’s memos, newsletters, meeting minutes and membership lists may fit into just one box, but that doesn’t diminish its importance, said Laura Schnitker, acting curator of mass media and culture special collections at the university. “We’re honored to get to steward this collection, to preserve these historical materials from underrepresented voices in public broadcasting,” she said.

The collection was donated by GLIPR co-founder Wesley Horner. Decades ago, he was executive producer of NPR’s Performance Today. Among his best friends was Carol Pierson, assistant manager at KQED. Horner and Pierson had worked together at WGBH.

The two often shared their experiences working as gays in public radio, “about what life was like,” Horner said. “We couldn’t really be out at work. Sort of, maybe, sometimes. But the culture was, we’d have to keep quieter than straight people and couldn’t really talk about what our lives were like outside work.”

They also heard from other gay colleagues at stations about problems within newsrooms. “We wanted to talk about stories in our community that ought to have been covered, but if we did, we were immediately suspect,” Horner recalled. Gays were perceived as “biased” in favor of gay issues, he said.

So he and Pierson decided it was time to tackle those and other challenges as a group.

GLIPR launched through a print newsletter, Outtakes. “We had get-togethers in D.C. to fold, stuff and mail,” Horner said. One Outtakes article from December 1992 reported on the launch of Denver-based KGAY, the first national daily radio network targeting gay and lesbian listeners. “Nothing on these airwaves to offend,” the story noted. “You’ll be bored before you’re titillated.”

Members also planned social events at the Public Radio Conference, then one of the system’s few national meetings. An early gathering took place during a PRC in San Francisco, Pierson said.

“We had an event at The Stud Bar, which is still there,” she said. “It was a chance to find out who the other gay people were who were working in public radio, since many of them were not out at that time.”

Schardt remembers those gatherings as valuable networking opportunities. “I met Wally Smith, a pretty big mover and shaker,” she said; Smith established the first NPR station in the Los Angeles market in 1972 and was a founding board member of American Public Radio. Schardt also met Frieda Werden of WINGS, the Women’s International News Gathering Service. “To be able to look around, to see and be seen was exciting,” Schardt said. “It definitely carried the feeling of coming out.”

The events soon proved to be extremely popular. “To our great surprise, they really attracted really big crowds — more than we could handle — of our straight friends,” Horner said.

Making lasting changes

The group also wanted to push for real change within the system. “We had the guts to decide that our topics were worth being discussed at PRC,” Horner said. “That was pretty much the only national gathering, so everyone was there.”

GLIPR sponsored PRC panels on how public radio stations could better serve gay and lesbian audiences and how to create diverse newsrooms inclusive of LGBT workers and their ideas. Panel moderators included Fresh Air host Terry Gross and Ray Suarez of Talk of the Nation.

Back then, the workplace atmosphere was far less accepting of gays, Horner said. “Who would have thought we’d ever have Ari Shapiro hosting All Things Considered?” he mused. “That was so far off our radar.” Shapiro, who publicly identifies as gay, married his longtime boyfriend in 2004.

Memos in the archives also reflect the group’s push for health insurance for domestic partners. “It was the old Catch-22. We had to prove we were married — but that wasn’t legal,” Horner said. But GLIPR did get NPR management to make the request of its insurance carrier. It was turned down, but that was a start. By 2002, NPR employees had that benefit.

Members also found their way to other groups. Pierson was active in GALS (Gay and Lesbian Staff) at KQED-FM, which was able to secure domestic-partner health coverage in 1994. She also served on the founding board of the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association, which is still active.

But GLIPR slowly faded away. “That’s the irony,” Horner said. “We wanted to be taken for granted. Ultimately we wanted it to be ordinary to come to work on a Monday morning and talk about what we did that weekend with our partner or the person we were dating. We wanted that to not be an issue. And we did get a lot closer to what we wanted.”

Pierson retired in 2010 as president of the National Federation of Community Broadcasters. Horner now lives in Cape Cod and consults with public radio stations on management and content development.

As for the archives, Schnitker is processing the GLIPR ephemera. Each item gets a “finding aid” identifier, which will be available for online search after the archives migrate to a new content management system in the near future.

Schnitker said the public broadcasting archive receives new collections fairly regularly. The university is now cataloging a fairly large collection, she said: David Giovannoni’s papers relating to his influential public radio audience-research work.

Did you attend GLIPR panels or social events? Share memories and photos in a comment below.

Correction: An earlier version of this post mistakenly reported that Carol Pierson worked at Monitor Radio.