Channeling Charles Siepmann for public media’s future

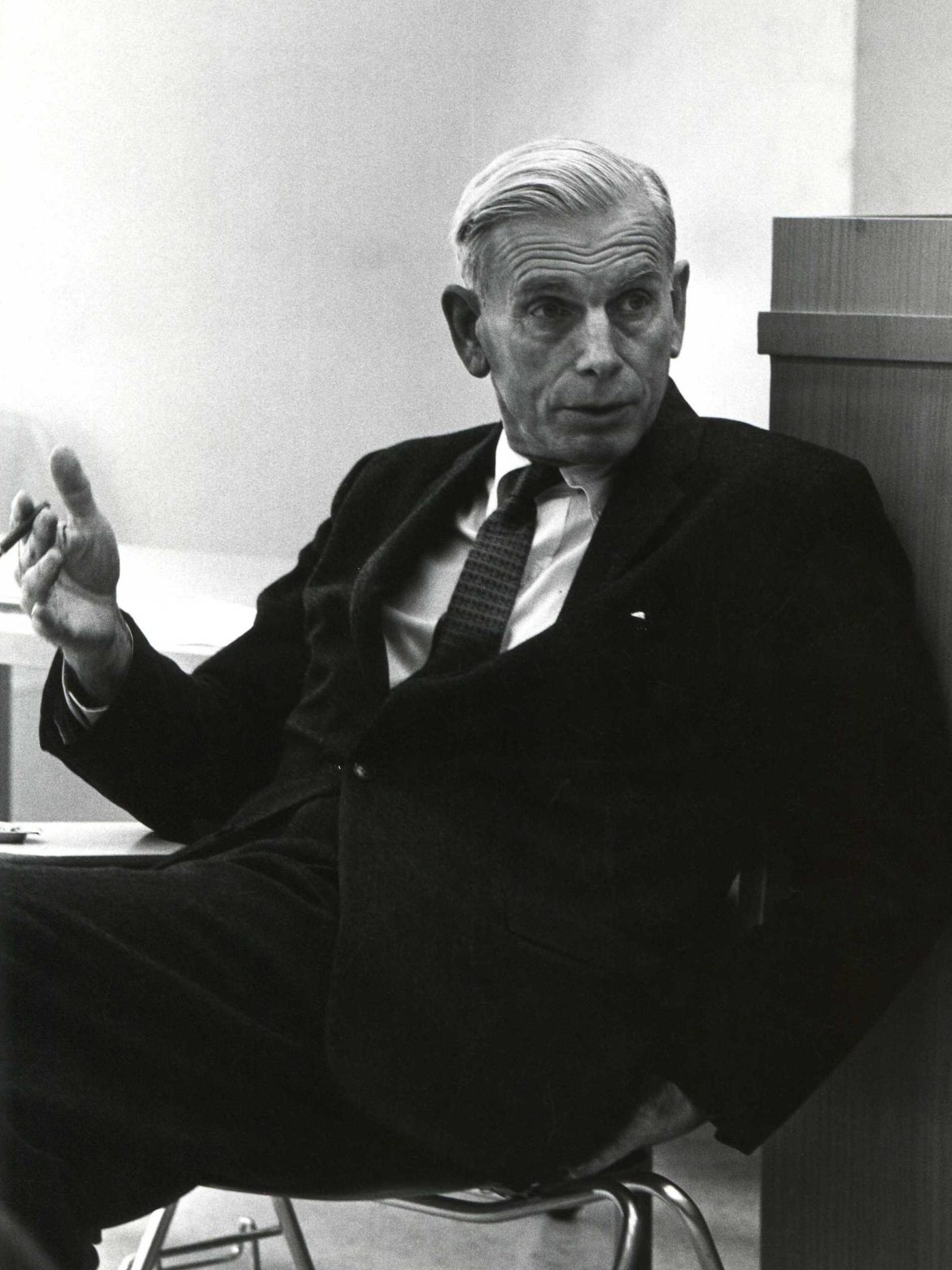

Siepmann in 1963. (Photo: HP7TwzDCBl, via Wikimedia Commons)

The media reformer and scholar Charles Siepmann (1899–1985) is all but forgotten today, but his legacy holds important implications for public media’s future. Siepmann represents a policy orientation that focuses on tensions and confrontations between democratic ideals and commercial imperatives in the American media system. During his long career, he always insisted that media institutions should be accountable to the communities they serve, arguing that an unchecked commercial media system could never provide for all of a democratic society’s communication needs.

Drawing from a longer study, I briefly summarize Siepmann’s media policy scholarship and advocacy while emphasizing some of his core arguments for why a strong public-oriented media system is essential for a democratic society. Reclaiming and foregrounding such democratic values could bolster rationales for protecting — and even expanding — public media into the digital future.

Siepmann’s legacy

A British-born, American-naturalized policy advocate, Siepmann played an instrumental role at the BBC in its early days. As programming director in the 1930s, he left a lasting imprint by pushing the BBC to broaden its appeal to diverse communities and to experiment with new formats and lively public service–oriented radio fare. (For example, he hired his friend Alistair Cooke to host what would eventually become the famous program Letter from America, which aired until 2004.)

He moved to the U.S. in 1939 to lecture at Harvard and then worked for the Office of War Information during World War II. In the mid-1940s, the FCC commissioned him to author its controversial “Blue Book,” which mandated that broadcasters devote a certain amount of time to local, experimental and advertising-free programming. The commercial broadcast industry aggressively fought back against these measures, accusing Siepmann and the FCC of trying to “BBC-ize” American radio.

Although the Blue Book was ultimately unsuccessful (largely due to Red-baiting), Siepmann never gave up fighting for media reform, even as he took refuge in the academy amidst growing Cold War–era repression in Washington, D.C., and across the nation. In 1946, New York University hired Siepmann to become the founding director of one of the first doctorate-granting communication programs in the country.

Mentoring dozens of media scholars and practitioners and authoring a number of influential books, Siepmann remained engaged with media policy debates throughout his academic career. His policy activism extended to Canada, where in 1949 he led a comprehensive survey of Canadian broadcasting for the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters, and Sciences (the “Massey Commission”). However, most of his efforts were focused on American media policy, where for over three decades he fought tirelessly to establish public-interest broadcasting. While advocating for a more socially responsible commercial media system, he also pushed for nonprofit educational programming. For example, he advised the National Educational Television Center (NET) during its struggle to define an American vision for educational/public broadcasting. He also was a key adviser on educational broadcasting for the Ford Foundation, which played an instrumental role in establishing American public broadcasting in the late 1960s.

Siepmann carried with him BBC-inspired assumptions about media’s role in a democratic society. Drawing from his 1959 FCC testimony on television’s future, he argued in a piece titled “Moral Aspects of Television” that broadcast media could enhance democracy only if public-interest policies were implemented. Otherwise, it was doubtful that an unregulated commercial broadcast system could carry out this task since purely market-driven values were antithetical to public service.

Speaking before the FCC in the late 1940s during debates that would culminate with the Fairness Doctrine, Siepmann called for a “liberty more precious” than broadcasters’ freedom to seek profits: “the freedom of the people to hear all sides of controversial issues.” He concluded that “Freedom of speech is a cherished privilege in a democracy. But there are other freedoms … which have to be accommodated,” especially “the freedom of the public to learn … all that may be learned in the free market of thought.” Commercial broadcasters, however, had little incentive to pursue this goal, because a “broadcaster’s prime interest is in profits.”

Arguing for a public right to access a diverse media system, Siepmann, in an activist pamphlet titled The Radio Listener’s Bill of Rights, urged listeners to engage in radio policy, reminding them that the “wavelengths of the air belong to the people of America.” Since AM radio was already dominated by a handful of media corporations, Siepmann believed that FM radio represented a “second chance” to establish public-interest programming. “Millions of us are dissatisfied with radio’s contribution to public service” and the “frequency of advertising,” he wrote. “What do we do about it?”

Siepmann’s social-democratic orientation had British roots but was ideologically aligned with the American New Deal project, as well as the Popular Front coalition of radicals and liberals, which lasted until the late 1940s. But as the political landscape rapidly gave way to anti-communist hysteria, these politics were cast outside the mainstream. Siepmann lost influence as his fellow media reformers were pressured to leave D.C., but he kept his progressive ideals alive as a scholar-activist within the new field of communication research. He continued to intervene in media policy debates throughout the ’50s and ’60s.

Siepmann’s policy approach saw value in a structurally diverse media system, a “mixed system” involving government protections, subsidies and active community engagement, while allowing both commercial and noncommercial media to flourish. This social-democratic orientation recognizes that critical services and infrastructures that are vital for a healthy democracy — including media institutions —should not be left entirely to the market.

Recovering Siepmann’s vision

Now is an opportune time to reacquaint ourselves with Siepmann’s social democratic logic. With American journalism in free fall as the newspaper industry collapses and as revenue-deprived digital journalism is often cluttered with invasive and deceptive ads, this critical juncture should be public media’s moment to step in where commercial news media have failed.

Unfortunately, for too many people, the notion of public media seems anachronistic. The internet seems to provide a proliferation of news sources, and radio is too often dismissed as a dying medium. Casual viewers may fail to discern the distinctions between PBS, with its “enhanced underwriting,” and commercial television. Moreover, public media is under constant political and economic pressure. At a time when the need for public media should be most self-evident, conservative politicians routinely target public broadcasting for proposed budget cuts. Concurrently, market pressures are further weakening public media, as dramatically exemplified with Sesame Street, one of PBS’s most celebrated shows for over 40 years, now airing first on HBO. Nonetheless, survey data consistently show high levels of support for public broadcasting, despite its compromised state, suggesting that Americans might accept arguments for increased subsidies.

With professional for-profit journalism withering away and cable television infatuated with Donald Trump, we may consider what a less commercial and more public media system might look like. Journalism produced within a public media model might be liberated from the relentless pursuit of ever-diminishing profits and could focus more on areas vacated by the commercial press, such as local, state-level and international news coverage. Community and public broadcast stations could transition into multimedia centers (as many already are) to create digital media across multiple platforms and support community-level investigative reporting, thereby expanding public media’s capacity, reach, diversity and relevance. Indeed, stepping in where the market fails is a natural role for public media. The BBC recently moved in this direction by announcing that it would fund 150 reporters at news organizations throughout the U.K. to focus on local journalism.

For American public media to follow suit would require increased subsidies. Unfortunately, and in stark contrast to global norms, our public media institutions remain impoverished. The U.S. is an outlier among leading democratic countries with its meager funding of public media from local, state and federal government: less than $4 per person per year. This is especially disheartening considering that research has shown how strong public media systems correlate with higher political knowledge.

Whether it’s nonstop sensationalistic election coverage or “clickbait” stories that privilege facile narratives with catchy headlines, excessive commercialism leads to various kinds of market biases and omissions. These tendencies in commercial media necessitate a public media alternative — a public option that pushes for-profit media to be more responsible and provide a wider selection of media fare as well as actual journalism.

Facing similar challenges decades ago, Charles Siepmann understood that we must rescue media’s democratic potential from commercial capture. Today’s public media advocates could follow his example by stressing democratic values while being clear about commercial media’s constraints. Given the problems facing our nation and our planet, we need public media more than ever before.

Victor Pickard is an associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication. His research focuses on the history and political economy of media institutions. He is the editor (with Robert McChesney) of Will the Last Reporter Please Turn Out the Lights and the author of America’s Battle for Media Democracy: The Triumph of Corporate Libertarianism and the Future of Media Reform. Follow him on Twitter.

This commentary appears as part of Rewind: The Roots of Public Media, our series of historical essays about public media created in partnership with the Radio Preservation Task Force. The RPTF is an initiative of the Library of Congress. Josh Shepperd, assistant professor of media studies at Catholic University in Washington, D.C., and national research director of the Radio Preservation Task Force, is Faculty Curator of the Rewind series. Email: shepperd@cua.edu

In making his argument, Pickering conveniently ignores the ’14 PEW study that describes NPR as; “The clear majority of its audience (67%) is left-of-center” and “only 3% of consistent conservatives trust NPR”. NPR editors/producers for whatever reason seem to get too many story ideas from Huffington, Salon, Kos, The Nation, Mother Jones etc…Perhaps the story selection is what the audience wants but it mocks the concept that NPR serves all the people.

Calling for an increase in subsidies won’t fly until NPR deals with the elephant in the room.

Then what about the representatives of the far left, some of whom write for the organizations you mentioned, who call NPR names like “Nice RePublican Radio,” accuse NPR of turning to the same conservative sources over and over again and as being deferring to corporate underwriters (despite the fact that firewalls are in place all over the organization)? As I’ve stated many times before, if the far left and far right nutcases hate NPR so much, it must be doing something right.

Tru dat. There are indeed groups like FAIR and many individuals calling for more Noam Chomsky or Mumia Abu Jamal. They want the radio they listen to, to sound more like Pacifico. Understandable.

However, the 67% left of center audience as measured by PEW, suggest NPR’s programing is already doing something to attract those left leaning listeners. NPR tilts left and has done so year, after year, after year. Conversely, the lack of conservative listeners points to systemic bias at NPR that turns the right off.

If that’s not the case, how do you read the PEW numbers?

I read the numbers this way: The extremes want their echo chamber. The far right finds it on commercial talk radio. The far left finds it on whatever stations carry “Democracy Now!” (which would in most cases mean community radio, which for the most part is much less political than the one-foot-in-the-grave Pacifica stations). Some may find it on commercial progressive talk radio, if it’s around–and let it be pointed out that the failure of Air America was due to business incompetence and a failure to realize that a large chunk of the left-of-center doesn’t care for call-in talk radio at all, whether it be Rush Limbaugh or Thom Hartmann. (That’s also the reason why “Talk of the Nation” isn’t on any more–those same listeners perceive Diane Rehm and Tom Ashbrook as less call-in talk and more interview and a number of the local shows on public radio are now more like the NPR drive time shows than call-in talk.)

In fact, I will posit that public radio’s ratings successes–and they are ratings successes when you are the top-rated or number 2 news-talk station in your market, as so many are in the PPM markets–are thanks to centrist and left-of-center listeners who got chased away from talk radio in the early 90s as most stations, inspired by the undeniable success of Limbaugh, converted to all-conservative hosts to superserve the most rabid listeners. It wasn’t an immediate thing–but if you look at the 12+ PPM numbers in market after market, the NPR news-talk station in most markets beats most conservative commercial talkers and is generally beaten by all-news formats or the few talk stations that didn’t go the right-wing route like WGN in Chicago. When a conservative talk station beats NPR, it’s usually because they either have an all-news block in morning drive like WSB in Atlanta or a strong live sports presence like WLW in Cincinnati. (KFI in Los Angeles has neither, but it’s an exception to the rule.) And the median age of NPR news-talk listeners may not be Gen X or millennial level, but it’s still younger than commercial conservative talk, which is getting older day-by-day.

And we all know that there’s one thing the far left and the far right agree on–how much they hate centrism. :)

You’ve laid out a fair argument. Still NPR leans left and it needs to balance its audience interest. Or, one day when CPB begs for funds from congress, they’ll find that ignoring a major audience segment isn’t a smart move.

But the far left will still claim that NPR is pandering to the right. Just consider the Bernie Bros that have been screaming that the net is “in the tank” for Hillary Clinton, a woman who is either an arch-conservative or a left-wing nutcase, according to what you read, but is neither. IF NPR is serving the center lane of American thought–and they are–they should have no problems getting CPB funding, whether directly or indirectly.

I studied and completed my Masters under Siepmann and will say he impacted me to this day. It is unfortunate that public TV and Radio never headed his words. They and much of the media focus too much on socialism vs providing open and unbiased communication on the world we live in.

Our education systems have failed us —-playing us at the bottom of the list on nations world wide. Perhaps Trump is exactly who and what we need for positive change to happen