How KBIA’s small newsroom won an Online News Association award

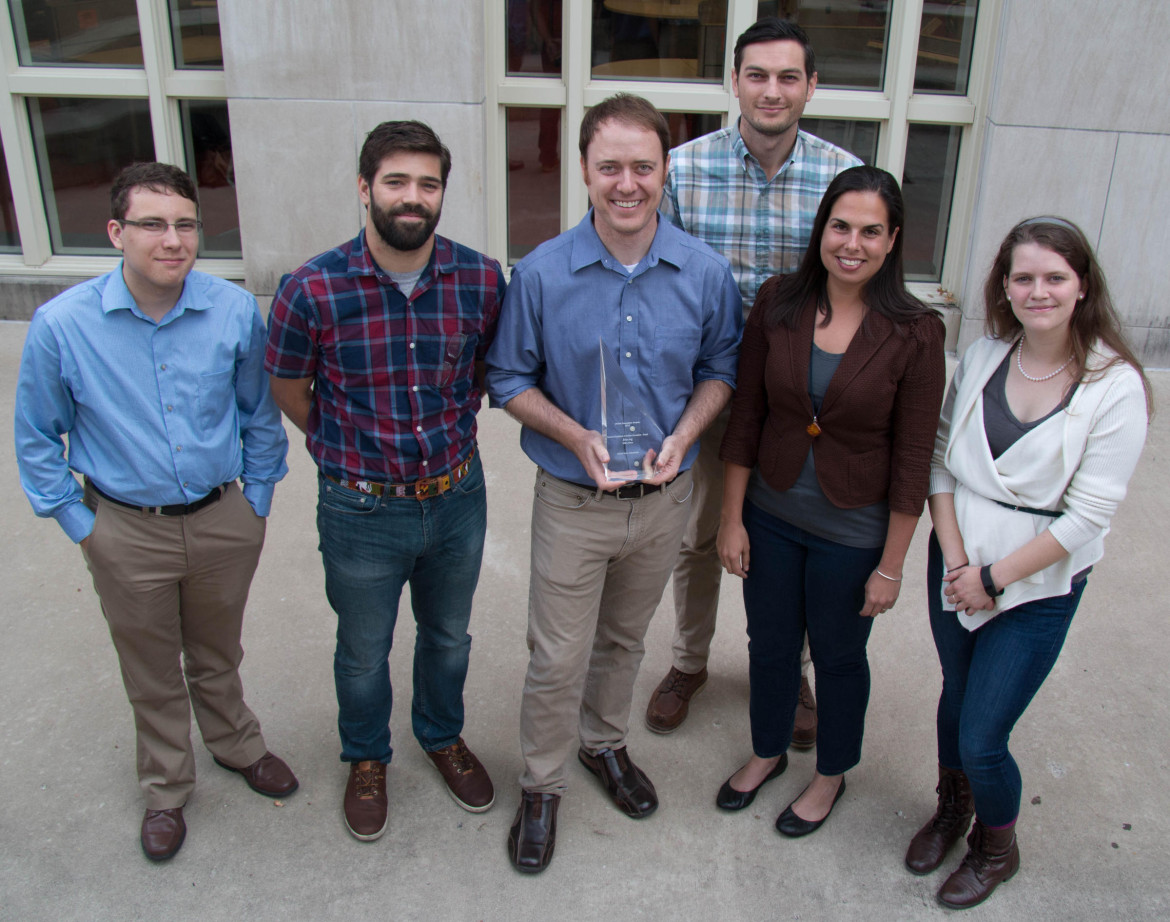

KBIA’s news team, from left: Nathan Lawrence, Bram Sable-Smith, Ryan Famuliner, Kristofor Husted, Sara Shahriari and Rebecca Smith. (Photo: Riley Beggin/KBIA)

KBIA’s news team, from left: Nathan Lawrence, Bram Sable-Smith, Ryan Famuliner, Kristofor Husted, Sara Shahriari and Rebecca Smith. (Photo: Riley Beggin/KBIA)

This is what KBIA’s website looked like almost exactly four years ago. Despite that travesty of a portal, kbia.org took home the general excellence award among small news organizations last month from the Online News Association’s Online Journalism Awards.

An editor from Current asked me to write a “how we did it” commentary to explain how this could have happened. I don’t want to pretend we have it all figured out, or that we deserved to win the ONA award over powerhouses like the Texas Tribune, MinnPost and the Honolulu Civil Beat. And it’s hard to summarize everything that we do. But to narrow it down to a short list of clichés, our progress in our online offerings can be boiled down to:

- Investment

- Collaboration

- Buy-in

- Impact

First, I need to explain a little bit about KBIA, because we’re a strange duck. We’re the NPR member station in Columbia, Mo., with six full-time news staff members and three part-timers. But we are also affiliated with the Missouri School of Journalism, and as such have trained hundreds of journalism students in our newsroom using the time-tested “Missouri Method” approach of a “teaching hospital” newsroom. Seventy to 100 students learn how to report, produce and edit in the KBIA newsroom each semester, many of them entering a newsroom for the first time.

Our dual missions — serving our local audience with high-quality content, and training young journalists — create a balancing act. Sometimes the missions overlap. Sometimes they don’t. But these two missions impact nearly everything we do at KBIA.

Investment

The roots of KBIA’s digital efforts technically stretch back to the early 2000s, but it’s fair to say that we didn’t focus major attention on our digital presence until 2011. That’s when KBIA hired its first digital content director, who oversaw the transition of kbia.org from a WordPress-based site to one of the first batch of sites under NPR Digital Services.

All of a sudden, we had a decent-looking site and a qualified person to manage our digital presence. Our former dumping ground for radio content became a new outlet that we believed could attract a new audience and allow us to tell stories in new ways. We started experimenting with video projects. KBIA news staff took part in the Knight 11-Week Intensive Digital News Training with NPR Digital Services. We kept experimenting, trying our hand at a hyperlocal podcast. And as we started looking around with fresh eyes, we realized we were living in a digital content candy store.

Our relationship with the University, and by proxy the Reynolds Journalism Institute, provides us with endless opportunities to experiment with innovative endeavors. That’s why KBIA created the Missouri Drone Journalism Project, which was experimenting with the technology long before they were a mainstream tool you could by off the shelf. That project with the MU Engineering School was funded by an on-campus grant meant to foster innovative interdisciplinary projects.

The same fund was used to create Access Missouri, a state government data project that was part of the ONA award entry. That project paired KBIA staff and journalism students with the MU Informatics Institute. We didn’t know how to clean data and build an interface. They didn’t know how to interpret the data in meaningful ways. We were able to do something together neither of us could do otherwise.

But all of these projects involve an investment of staff time, and often hard cash. And if we didn’t have the people or staff, we had to go out and write grants or look for major donors who want to support these kinds of projects. There wasn’t some grant writer putting together the proposals for the drone project and Access Missouri. News staff members themselves crafted the pitch and landed the funding. There’s a basic truth about in-depth news gathering that many journalists shy away from for ethical concerns. Frankly: If we want to do extra stuff, we often need to find ways to pay for it ourselves.

Collaboration

At KBIA, we are serial collaborators. Three of our six news staff members report for Local Journalism Centers (Harvest Public Media and Side Effects). Shortage in Rich Land, which was part of the winning ONA entry, was actually a collaboration between reporters on both of the LJCs. The other parts of the entry, Here Say, Heartland, Missouri, and Exploring the Paths of Missouri’s Special Education were pro-am special projects with KBIA staff and students, and the buildouts in Atavist were overseen by our digital content director. We’ve also collaborated with the local newspaper and the public television station in St. Louis in recent years.

I think our strange arrangement makes us more willing to enter into collaborations, because our daily tasks and staff are already so varied. But we are also just like every other member station: Our resources are limited, and our staff is spread thin. Our collaborations allow us to leverage our resources to try to “punch above our weight class.” Sometimes we swing and miss. Access Missouri grew out of a (mostly) failed collaboration called Project Open Vault. But we learned from that project, and it’s helped some of our future collaborations.

When I’m considering a new collaboration, I’ve learned to cut to the chase quickly. People that don’t collaborate often like to dream about the idea, which does have value, of course. But they’ll make loose promises, or have unclear goals. People love to sit around a table and talk about an idea, but sometimes it’s harder to get them to actually start doing.

I’ve found myself forcing everyone’s cards on the table at the first meeting. I’ll ask point blank: “What does everyone need to get out of this collaboration to consider it a success? What can everyone commit to the project? Are there ways for everyone to fit this into their existing workflow? If not, how — specifically — will the new tasks be handled? Do we need to try to find grant money or some other form of support to make this work? Do we need to find a way to make the collaboration sustainable, or are we all OK if this is a one-time project?

If we don’t come away with clear direction and a list of action items from the first meeting, I don’t like the collaboration’s chances.

Buy-in

One of our biggest perceived weaknesses at KBIA is also one of our biggest strengths when it comes to our digital content. We are a small-market radio station, and staff turnover is always high. Often our hires are entry-level — they put in a few years and move on to great jobs in bigger markets. We currently have no news staff members over the age of 40, and typically most of them are under 30. Our young news staff members may not have a lot experience, but they have high digital-literacy levels, and we don’t have to try to convince anyone that our online presence is important.

Pivotally, our General Manager also actively encourages experimentation in the digital space, understanding its importance to the viability of our station in the long term. We don’t have to manage up. It doesn’t hurt that our cume rating is consistently in the top 10 of all member stations, and that there’s not much competition for local radio news in our market. We can afford to experiment in the digital space because our terrestrial presence is locked down.

So, buy-in to the importance of digital content is not often a challenge at KBIA. When it is, we pull out Barbara Cochran’s white paper, “Rethinking Public Media: More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive.” Most of the projects we’ve created at KBIA are in line with Cochran’s guidance.

Impact

If you’ve made it this far in the article, I likely don’t have to explain PRPD’s five tiers of news coverage to you. While we don’t always hit the highest tiers, I love to use this outline to explain what we try to do at KBIA. We do everything we can to allocate our highest-value resources to in-depth projects that can have impact in our community. We do that by limiting the beasts we need to feed, or finding ways to get them fed with minimal distraction from that goal.

Some local newsrooms have actually eliminated local newscasts altogether. We haven’t gone that far. In fact, we are about to add hourly newscasts midday as our station undergoes a format change to all-news. This is where we utilize the students working in our newsroom. Aside from the most important local stories, we have students cover most of our daily news. Because of the students’ low levels of experience, often these stories are not fit for air. Multiple editors work on each story to determine if it ever goes to air. If the story gets filed away in the garbage can, the scale tilts completely toward the educational mission and away from the mission to serve our audience. Very little of this content hits the digital space.

Most of our anchors are also students, overseen by professional staff. Our audience is (mostly) OK with the changing cast of characters on air, because they understand our dual missions (an NBC-affiliate TV station and a local daily newspaper operate in the same way through the university). The anchors often rely on Associated Press content for the newscasts when there are no quality student stories to air.

We make sure not to miss the important daily stories. But we wouldn’t be considered the local news leader for breaking news and don’t aspire to be.

The way I like to explain the five tiers is that you can report two ways: You can rush to the scene. Or you can wait to find out what happened and decide if it’s worth your resources and your audience’s time. Then, you can try to provide context to the situation, when oftentimes the rest of the reporters are busy chasing the next thing.

Rather than being the sixth microphone on the scene, I’d rather KBIA have the only microphone somewhere else. We believe this approach is in line with the niche NPR has carved out for itself. When we used that approach to cover the unrest in Ferguson, Mo., it won us a National Edward R. Murrow Award for feature reporting.

But we can also mobilize our students to serve that larger mission. Every semester we have some students that actually have interest in careers in public media. These students stick around beyond that initial semester and get pulled onto special projects where they work alongside our professional producers. It takes a lot of work, and there may be years of grooming before our local audience benefits from the fruit of these labors.

The students that worked with KBIA staff on the documentary “Heartland, Missouri” are now a reporter at Nevada Public Radio and an intern at Radiolab. The student that pitched in on our Ferguson story just started a reporting job at Wisconsin Public Radio. We’re in the process of developing a public radio-–specific curriculum at the MU journalism school to better solidify this training ground and attract more students capable of high-caliber work to KBIA. It will serve both of our dual missions.

The takeaway

By now, you’ve realized this is not a “We ONA’d and you can too” guide. We have a unique situation at KBIA that would be hard to replicate elsewhere. But what can be replicated is the assessment of a station’s infrastructure and community resources to figure out ways to do more. Often this puts us outside of our comfort zone, and it can involve a lot of risk. But if a newsroom leans into that uncertainty, it can open up great opportunities.

Ryan Famuliner is the news director of KBIA-FM and an assistant professor at the University of Missouri School of Journalism.