New films remember video avant garde of the 1970s

Alan and Susan Raymond were among the filmmakers involved with the pioneering TV Lab. (Photo: Video Verite Archives)

Husband-and-wife documentary producers Alan and Susan Raymond made their first big splash on PBS in 1973 with the cinema-verité series An American Family. But they say The Police Tapes, their 90-minute video-verité doc about a South Bronx police precinct, is what really put them on the map.

“I always looked back at that as a turning point in our career,” Alan Raymond said of the 1976 production.

The Police Tapes was commissioned by the TV Lab at WNET in New York, which served as an incubator for a colorful group of independent producers, including the Raymonds, from 1972–84. Now the work from the pioneering TV Lab is the subject of a forthcoming documentary by Howard Weinberg, who had a distinguished producing career in public and commercial TV.

Nam June Paik & TV Lab: License to Create, which screened in New York last month, chronicles the documentarians, video artists and dramatists who made up the remarkable stable of television talent at TV Lab. Another documentary, Here Come the Videofreex, focuses on a counterculture video collective that was born at Woodstock, produced programs for TV Lab and nearly landed a show on CBS.

The Sony Portapak, a portable video recording system, spawned some of the experimentation in WNET’s TV Lab and enabled the formation of a slew of groups focusing on portable video by the early 1970s. “It was a democratizing technology,” Alan Raymond said of the portable video gear. “It was a seismic shift in accessibility.”

The Raymonds shot An American Family with color film, but for their doc about the New York Police Department’s 44th Precinct they used the first generation of portable video gear — a beat-up black-and-white Portapak that had belonged to the Korean-born video artist Nam June Paik.

The Portapak recorded on half-inch reel-to-reel videotape. Between the recording deck and a separate camera, the gear weighed more than 20 pounds. By today’s standards, the images it produced were crude. But at the time, that quality gave The Police Tapes a film-noir look.

WNET’s broadcast of The Police Tapes garnered a local Emmy Award, a duPont-Columbia and a Peabody. PBS declined to air it on technical grounds, but the ABC television network had no such qualms. It broadcast a 52-minute version of the documentary, which went on to win three national Emmys in 1977. Afterwards, the Raymonds went to work for ABC News and later started a long association with HBO.

The Raymonds’ career path — from groundbreaking public TV productions to the commercial networks and even Hollywood — was shared by other video pioneers.

Weinberg worked at WNET during the TV Lab era, playing key roles at The MacNeil/Lehrer Report, The Dick Cavett Show and Bill Moyers’ Journal. He moved to CBS, producing segments for 60 Minutes and Sunday Morning, where he profiled Paik in 1982, the same year the Whitney Museum staged a Paik retrospective.

Weinberg met Paik in the mid-1960s, when the artist came to the U.S. Widely credited as the father of video art, Paik was a composer, sculptor and performer who collaborated with such avant-garde New Yorkers as John Cage, Merce Cunningham and Yoko Ono. In a September 2014 New York Times review of an exhibit of Paik’s work at the Asia Society in Manhattan, art critic Holland Cotter called Paik “a prescient thinker as well as a born entertainer.”

Paik was an artist-in-residence at TV Lab from 1972–76 and again from 1983–84. The TV Lab also collaborated with experimental filmmaker Ed Emshwiller, photographer William Wegman and his not-yet-famous Weimaraner Man Ray, choreographer Twyla Tharp and filmmaker Shirley Clarke, who videotaped 20 transvestites wearing tutus for a piece that never aired.

TV Lab was run by David Loxton, who had previously worked on Great Performances. Loxton, who is fondly remembered by WNET staffers of the time and TV Lab’s independent producers, passed away in 1989 at the age of 46.

“We never thought in those days that we were competing with commercial television,” Weinberg says of his work at WNET in the 1970s. “We thought that we were the research and development arm of television itself. That was the philosophy that motivated us.”

TV Lab shut down in 1984 after CPB decided to invest in Frontline instead.

“To a certain extent, it had run its course,” Weinberg says of TV Lab by the mid-1980s. “Galleries were showing video art, and portable video was used widely in the production of documentaries.”

TV Lab’s embrace of independent producers amounted to an “extraordinary moment of sunshine, both in terms of content and in terms of technology,” said Jon Alpert, whose early documentaries aired on WNET thanks to TV Lab.

Alpert co-founded the Downtown Community TV Center in Manhattan with Keiko Tsuno in 1972. They were the first American TV crew to visit Vietnam after the war, and their Vietnam: Picking Up the Pieces, also shot with a Portapak, aired on WNET in 1978. Their earlier documentary, Healthcare: Your Money or Your Life, was also produced through TV Lab.

DCTV, which has won 16 national Emmys over the years for documentaries it produced for HBO, is the only one of the dozen or so portable video groups in New York of the era to survive. Operating out of a former firehouse it owns in Chinatown, the group runs classes in video production and rents video equipment to indie producers.

Reached in Miami, where he was shooting an HBO doc about a boot camp for troubled young men, Alpert fondly recalled TV Lab engineer John Godfrey, who is featured in Weinberg’s documentary. Godfrey wrestled with the “crummy video” independent producers recorded and got it to broadcast quality, Alpert said.

Though the materials were rough, the end product was cutting-edge. Alpert laments that such innovation has declined in public TV.

“It would be nice to say that public broadcasting remains in the forefront in terms of technology and content, but the reality is that it’s not. And to some degree, that’s a tragedy,” Alpert said. “All of us who were involved in those exciting times working with PBS have found other places to work.”

TV Lab “put video art and drama and documentary and animation and anything that was interesting in a place, and these people rubbed up against each other and they were part of the station, which as a whole was an incredibly creative force,” Weinberg said.

The Freex come out

In addition to DCTV’s early docs, TV Lab aired docs shot with Portapaks by the group TVTV (Top Value Television), including Lord of the Universe, a 1974 examination of the teenage “perfect spiritual master” Guru Maharaj Ji. TVTV also produced Gerald Ford’s America, a four-part series about the first 100 days of the Ford administration, shot with the first color Portapaks.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I6kHW2qNe9M

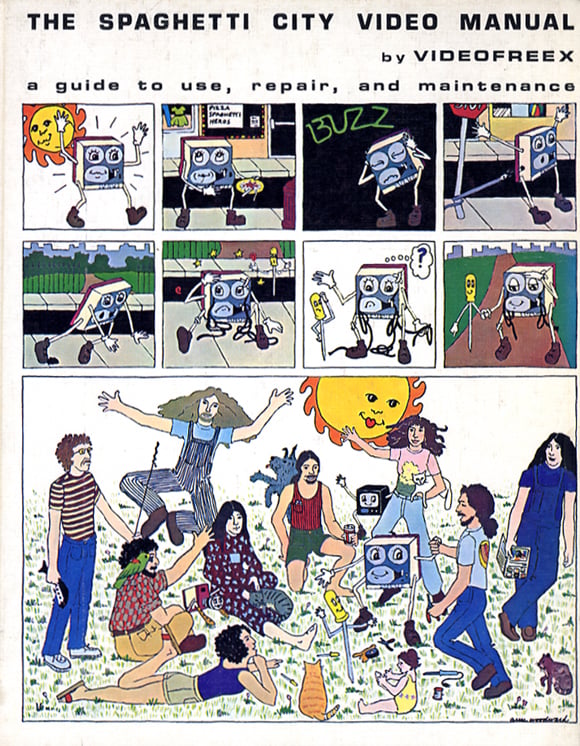

One of TVTV’s key producers, Michael Shamberg, eventually settled in Hollywood and became a producer of major motion pictures. During his counterculture days, Shamberg wrote Guerrilla Television, an influential manifesto for the portable video movement. Used copies of another bible of the movement, The Spaghetti City Video Manual, fetch more than $800 online.

That manual was written by the Videofreex, a countercultural video collective that is now the focus of an exhibition at the State University of New York at New Paltz and an upcoming documentary, Here Come the Videofreex. The film will have its world premiere April 10 at the Full Frame Film Festival in Durham, N.C.

The collective formed in Manhattan in the wake of Woodstock, then relocated to the Catskill Mountains, where its members lived communally, ran a pirate TV station and produced programs for TV Lab.

Two weeks after Woodstock, Cain and her boss met with the newly formed Videofreex, who were hired to produce Subject to Change, a replacement for the Smothers Brothers. In mid-December, executives from the Tiffany Network visited the Videofreex loft in Soho to watch the pilot. It did not go well.

“They couldn’t stand it,” recalls Cain, who, along with her boss, lost her job at CBS soon after the screening. She promptly joined the Videofreex.

“We didn’t know what CBS wanted to do, but we knew what we wanted to do,” she told Current. “We knew exactly the path that we were on. We just continued on.”

In 1971 the Videofreex moved to the Catskills, where they rented a large house for $300 a month and started their pirate TV station, Lanesville TV. Cain recounts their adventures in her memoir Video Days: and What We Saw Through the Viewfinder.

Some of the Videofreex are still making television. “I’m doing the same thing I did 45 years ago,” said Bart Friedman, who stayed in the Catskills. Friedman shoots videos for arts organizations, and his company, Reelizations Media, produces videos about addiction recovery and relapse prevention. He is a member of the community board that oversees the public-access cable TV channel in Saugerties, N.Y., and also produces videos for that channel.

Though the vox populi media of pirate TV and public-access cable channels may have been supplanted in the me-media era of smartphones by high-definition video, Skip Blumberg, another member of the Videofreex, has posted a number of his productions on YouTube.

Blumberg and Cain were both involved with The 90’s, a PBS series shot with camcorders that had a 53-episode run from 1989–92. Blumberg went on to produce films for Sesame Street and National Geographic, and has won three Emmys.

He looks back fondly on the group’s role in training hundreds of people to use that first generation of portable video gear in the 1970s. The New York State Council on the Arts, which embraced video as a new art form, funded much of that work.

“It’s not like we caused a lot of the changes that happened,” Blumberg said. “We just got there first.”

The Videofreex recorded or produced upwards of 1,500 videotapes, many of which are housed at the Video Data Bank, affiliated with the Art Institute of Chicago. So far, a couple hundred tapes have been digitized, financed by grants and sales of footage.

For further reading:

- Videofreex Archive at the Video Data Bank

- Videofreex: America’s First Pirate TV Station & the Catskills Collective That Turned It On, Parry D. Teasdale

- Video Days: And What We Saw Through The Viewfinder, Nancy Cain