Barriers to newsroom collaborations lower than pubcasters think

“Neither journalism nor public life will move forward until the public actually rethinks and reinterprets what journalism is: not the science or information of culture, but its poetry and conversation.” — James Carey, “The Mass Media and Democracy,” Journal of International Affairs, June 22, 1993

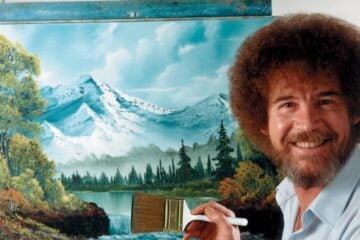

Public media’s recent award-winning journalism collaborations include StateImpact Oklahoma, which received a Sigma Delta Chi award from the Society of Professional Journalists for its coverage of the tornado that devastated Moore, Okla., last year. (Photo: Joe Wertz, StateImpact Oklahoma)

Since 2009, CPB has provided approximately $23.2 million to establish more than 40 journalism partnerships at public broadcasting stations.

These included Project Argo, a collection of topically focused local blogs produced by NPR and 12 public radio stations; and the Association of Independents in Radio’s Localore, a cross-platform radio and television content partnership that paired indie producers with 10 stations.

CPB’s investments in nine Local Journalism Centers have been the most ambitious of these initiatives. These collaborations involved 56 public stations of various licensee types and enabled multimedia production across public radio, television and digital platforms.

Many of these collaborative projects operated independently of host stations’ newsrooms, and they departed from the normal broadcast-centered practices and routines to create additional content about specific topics.

Public radio distributors and outside journalism organizations have also laid the roadbed for collaborative journalism through projects such as NPR’s State Impact initiative, Public Radio International’s state-accountability series and Public Radio Exchange’s new investigative program, Reveal.

These partnerships have brought new talent and new skill sets into public radio newsrooms and provided valuable public service journalism focused on specialized topics; some have won prestigious awards.

But as I see it, the progress in creating new models for building a better public media news service has been limited to those stations and distributors that received grants to carry out this work. If public media is to step up its newsgathering and its role in informing local communities, this has to change. Many of my colleagues believe there are barriers to collaborative newsgathering, yet stations across the system will benefit from the resources and talent such alliances will bring to their newsrooms.

Public broadcasting’s national leaders see not only economic advantages in ongoing alliances among local stations but also a new prototype for digital and broadcast content creation. Fueled by CPB incentives in 2009, public television stations have developed partnerships that are mostly directed at economic savings and expense sharing through, for example, combined master-control operations, consolidated underwriting sales and shared database management.

New Hampshire PTV and Boston’s WGBH have gone the furthest with this, with their 2012 regional partnership to coordinate their programming and share back-office operations.

These alliances differ from cooperative journalism projects because they streamline public media’s infrastructure while supporting local PTV operations; journalism partnerships require deeper levels of collaboration and commitment because they involve creating content. But PTV leaders who have moved to consolidate their operations recognized that the savings achieved through these efficiencies may be the only avenue for ramping up their local production capacity

Public radio offers its own examples of ongoing collaboration in creating content. State and regional news-sharing services, state capital–reporting consortia and ambitious journalism collaboratives such as the Northwest News Network demonstrate that when local stations join forces and combine resources, they can create more significant regional coverage.

CPB has just awarded funding to a newsroom collaboration among five New York stations. Unlike the LJCs, Upstate Insight will produce coverage about multiple topics for an entire region. It is specifically intended to add muscle to participating stations’ regional newsgathering capacity.

The most vocal public media leader advocating for ongoing partnership models is Bruce Theriault, CPB’s senior v.p. of radio. Theriault sees production partnerships as not just an evolution of the status quo but as a superior system model. He calls it “a neural network of locally based stations and national producers.”

In driving local journalism partnerships around “content verticals” of specialized news coverage produced by the Argo Network bloggers, LJCs or cross-media pilots of Localore, CPB has actively encouraged radio and television stations to develop sustainable, ongoing collaborations producing content on a local or regional basis. According to Theriault, these newsgathering partnerships allow the field to “create the scale and capacity needed to produce high-quality original journalism at local/regional public media companies across many communities and strengthen the national programs in the process.”

Stations have embraced back-office efficiencies and applied for project-based partnership grants, but there’s clearly a wariness among local public media leaders about diving into these relationships on an ongoing basis without incentives. Few public media stations have initiated journalism collaboratives in which they produce all of their daily coverage in alliance with partners.

And while the rhetoric — and logic — of public media executives like Theriault is inspiring, he and other national leaders must tread delicately in advocating for wider adoption of this model. Local public media folks often impulsively suspect that heeding counsel from the Beltway is the shortcut to subjugation.

And — let’s face it — there are obstacles that preclude partnerships from being adopted wholesale across the public media system. Stations that have ample resources may see few advantages in a regional journalism collaboration if all their potential partner stations are resource-poor. And it is probably puerile to expect intensely competitive same-market stations such as WBUR and WGBH in Boston to suddenly forge a daily production partnership.

Still, scores of stations are positioned to potentially benefit from daily journalism production partnerships. From a distance, one can see little downside for those with limited news staffs to pool their resources, talent and community connections into an ongoing multistation service.

What’s the hitch that prevents more stations from pursuing collaborations?

Some of the explanations that I’ve heard about this don’t ring true. Yes — some stations are deeply averse to change. But can they afford to resist it, given the ways that digital technology is disrupting distribution and consumption of news? For those who say shared decision-making is anathema, I don’t buy it. We are all media professionals who share public service missions and values.

Partnerships, though, require more than a spiritual affinity. The success of any partnership rests on three things: clear goals; an agreed-upon framework for content mission, design, and execution; and evaluative standards.

In other words, participants in a partnership — whether they are a small assembly of stations or hundreds of stations in a local-national alliance — must arrive upon a precept, a governing strategy for creating journalistic content collaboratively.

If the individual entities entering the partnership do not “know themselves” — that is, if they haven’t designed viable journalism strategies within their own institutions — they cannot begin the process of directing their talent and resources in a multistation collaboration.

So this is the obstacle that I see: Too many public media news organizations haven’t defined their own journalism strategies to begin with.

Balancing theory and practice

It’s rare that a strategic plan developed at a station explicitly addresses the nature and purpose of the institution’s journalism, which is the heart of the public service performed by most public radio stations and their affiliated producing organizations. True, strategic plans often articulate a station’s journalistic mission as well as its aspirations for institutional significance through contributing to civic health. But details of how a station’s journalistic content will be distinctively fashioned to realize these ambitions are often unaddressed.

Reveal, a new investigative series from Public Radio Exchange and the Center for Investigative Reporting, received a Peabody for its examination of the over-prescription of opiate drugs by the Department of Veteran Affairs. (Photo: Adithya Sambamurthy)

In discussing this, I often encounter a countervailing argument that echoes a Yogi Berra quip: “In theory there’s no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.”

The parry maintains that planning journalism doesn’t amount to a hill of beans in the crazy world of newsgathering. It is not only impossible to plan journalism, but arrogant, even prejudicial.

This attitude has a surface logic to it: News just happens and it needs to be covered. The rationale for coverage is often shaped in the moment: the preferences of news directors and editors, the proclivity of reporters, a scoop tweeted from a connected source. Newsroom decisions are not immune to the practical demands of operational needs.

But the electricity of newsgathering also shapes daily coverage. As our journalists are exposed to breaking information issued by many competitors on multiple platforms, repeated and revisited within a compressed period of time, they feel obligated to join in. As the speed of the daily news cycle accelerates, the public media journalists must respond more quickly or risk appearing out of touch.

The practice of chronicling news events is an aspect of public-service journalism, but when a station’s news content boils down to a daybook of facts, the news chooses us, not vice versa.

So news happens, but journalism is made. Any communication about news — a tweet, a blog post, a YouTube video, a front-page article, an in-depth expose, a documentary film, a Facebook post — is the result of human action and human choices.

The shape of our journalism is under our control. The decisions made in our newsrooms about how to document and amplify local events, policy issues and civic dialogue can and should be a matter of design that advances mission. They should not be a patchwork of random approaches.

Tim Eby, general manager of St. Louis Public Radio, recently saw his newsroom of radio reporters swell with the addition of many competent, seasoned reporters and editors from the now-defunct St. Louis Beacon online news site. Eby’s management team, which includes Editor Margaret Wolf Freivogel and Director of Radio Programming and Operations Robert Peterson, now oversees 30 full-time reporters and another five full-time talk-show producers. (story, page 3).

Their reaction to the sudden addition of all this reporting muscle was not to report more news but to create better journalistic choices. Thinking strategically, Eby says, became the only way to have an institutional impact.

“We must commit to a disciplined approach because we will never have the resources to do everything,” Eby says. “Local institutions need to look at the competitive sources for local journalism and build choices in that environment, because that’s the world in which our audience lives.”

“As local public media, we have an obligation to see where the community’s mainstream and independent news competitors are not serving,” he says. “Filling that void is our audience’s highest need.”

Consequently, staff designed St. Louis Public Radio’s journalism strategy to focus on the most relevant local topics. Desks within the newsroom produce coverage of science, justice, politics, education and innovation. Some specialists on the news team produce in-depth, high-impact coverage, such as Chris McDaniel’s reporting on lethal injection in the Missouri penal system.

St. Louis Public Radio’s service plan is thus tailored to the station’s capabilities and the needs of the community it serves, at this moment in the community’s evolution.

In designing a journalism strategy, a public media institution might opt to focus its reporting on a few topics that warrant ongoing coverage, as St. Louis Public Radio has done; or it may emphasize long-form reporting over spot news. Though many public radio newsrooms aspire to produce nuanced, in-depth coverage, a station may identify a local need for spot-news reporting that outweighs long-form, particularly in communities where competing news organizations are unreliable or politicized.

The point is, strategies cannot be store-bought. If each station is to succeed in shaping its news coverage in ways that deliver valuable public service, its strategy will differ based on the institution and the community it serves. As Eby says, each public media institution must create a journalism strategy and “discipline” itself to realize it.

A journalism strategy clarifies and prioritizes coverage choices, building on the expertise of staff and establishing a rationale that guides decisions about how to direct the resources of the newsroom. It affects the design of digital and traditional newsgathering and helps news directors and reporters navigate the relentless flow of information coming at them to produce content that is relevant, distinctive and essential within the competitive news environment and the social and civic needs of their communities. As part of an overall institutional plan, it illuminates how other institutional goals — from marketing to revenue generation to engagement — will reach desired outcomes.

Path to partnership

A public media organization that has defined its own journalism strategy is in the best position to weigh how its goals and aspirations can be combined, reimagined and achieved with prospective partners. Station leadership can look beyond opportunities for grant-funding or simple cost-sharing and assess the potential for impact in their communities.

Collaborative partnerships that are rooted in journalism strategies of individual stations will reflect the basic values, goals and aspirations of each partner. Participants can immediately see the common ground between them and identify the disparities which must be negotiated. Those conversations aren’t a cakewalk but in the end may yield a wider, more welcoming arena of discourse, discussion, discovery and debate.

The work of crafting a small-scale regional journalism collaboration provides opportunities for stations to conceive of their place-specific work in ways that transcend the parochial; participating stations develop a shared appreciation of issues in the public dialogue and universal aspirations to serve multiple publics. The small-scale partnership opens more options for cross-geographic discourse and engagement.

Participants in such alliances might choose to take advantage of participatory media more aggressively or experiment with digital platforms that serve to deepen and contextualize newsgathering. Partnerships may make it possible to employ online editorial hubs, video training of citizen journalists, and multiple nontraditional editorial techniques. The Fibonacci spiral of ever-ballooning audience expectations for digital contact and content may become more manageable and may be delivered more expertly in an alliance, including the meaningful employment of social media for the partners and their station journalists.

All of this planning around journalism may lead to the kind of system Theriault and other thought leaders have envisioned. But it has to start within each institution — then the specific plans of individual stations can be mutually crafted to fit within a new, governing collaboration plan on a regional or national scale.

Collaborative strategic planning is difficult; plans won’t succeed if they are imposed. They must be designed by all the participants in a group process and reflect the aligned ambition of all the partner institutions. In a collaborative structure, all the partners must embrace, preach and practice the same plan.

And it is certainly possible that, even with the best intentions, a group of individual stations within a city or region cannot agree on a collaborative plan. When negotiations for content partnerships hit a stalemate, it’s probably unrealistic to consider an ongoing daily collaboration among newsrooms. Project partnerships may be all that are possible, and they could provide a good starting point for a future re-examination of a more comprehensive ongoing collaboration.

For individual stations, there is merit in designing a journalism strategy, no matter what. Since the strategy is derived from a community-driven set of needs, it sets down key criteria that can guide newsroom decisions on a day-to-day basis. It demands the application of editorial insight and analysis of the nature, scope and meaning of news ready to be communicated.

As each station navigates its journalistic purpose strategically, it positions itself well for forming editorial partnerships and maintaining an equal and influential role with collaborators — whether they are public stations or other public-service–minded news organizations.

As each station navigates its journalistic purpose strategically, it positions itself well for forming editorial partnerships and maintaining an equal and influential role with collaborators — whether they are public stations or other public-service–minded news organizations.

And most importantly, the nation is enriched community by community as stations craft journalism about public issues, challenges and accomplishments in ways that are relevant, essential and unduplicated.

Chicago journalist Torey Malatia chairs the board of directors of Public Radio Exchange Inc. in Cambridge, Mass. With Ira Glass, he co-founded This American Life, a national production for which Malatia provided 18 years of “management oversight” as president of Chicago Public Media.

Correction: A photo caption in an earlier version of this commentary incorrectly stated that StateImpact Oklahoma won a national Murrow award for its coverage of the tornado that devastated Moore, Okla., last year. It received a Sigma Delta Chi award from the Society of Professional Journalists.