Pubcaster’s memoir details creative early years at WQED

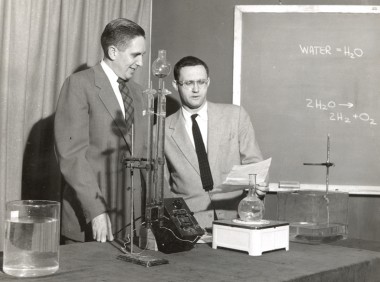

Norbert Nathanson, right, directs an instructional high school science course for Pittsburgh's WQED during its first years on the air. (Photo: Nathanson)

When Norbert Nathanson, one of the first employees of WQED in Pittsburgh, sat down to write 15 years ago, he didn’t intend to author a memoir.

“I just wanted to tell the story of my life for my own children,” Nathanson said. But once friends read his recollections, “they just kept telling me, ‘You really should publish it.’”

A Secretly Handicapped Man, out in October (North Wind Publishing), is not only the story of Nathanson’s place in the history of public broadcasting, but also the tale of his struggle with his own body and society’s attitude toward him: He was born without feet and one hand.

But thanks to a strong pragmatic spirit and a bold surgical procedure, Nathanson achieved a successful career. He worked alongside Fred Rogers and illustrated a book by the children’s television icon. Nathanson taught college classes in broadcasting and worked in several government posts. In a position with New York state, he helped put several pubTV stations on the air — including New York City’s WNET — before getting his “dream job” as an executive at WMHT in Schenectady.

Living that full life was a battle. “In the space of 70 years I was variously labeled as crippled, deformed, handicapped and disabled, more recently as a person with disabilities, and currently as physically challenged,” he writes in the book. “The evolving choice of epithets traces the gradual changes in societal perceptions, but all these terms have a common theme; they designate someone who is different.”

Nathanson got involved with WQED, the nation’s first community-supported television station, as a volunteer art director in 1953, before the station was on the air. With a degree in industrial design, he turned his volunteer gig into a full-time job in 1954.

Among the visuals that Norbert Nathanson created for WQED was a sketch that greeted viewers on the station’s first day on the air, April 1, 1954. (Image: Nathanson)

“When WQED was created I became a volunteer, and as such I was permitted to try anything — thus I proved what I could do beyond what my appearance suggested,” he said.

His first assignment at the station came from Rogers, who was then director of children’s programs. As Nathanson wrote in a remembrance of his initial days at the station: “As soon as Fred learned I was an artist, he had an immediate request of me. ‘You know, NBC has their three chimes, ‘Bong, bong, bong’? WQED is going to have five notes. Could you design a visual for it?’ . . . . Next morning I was back with a plan for Fred’s visual and two blueprints with construction details made at my own expense.”

Nathanson also drew WQED’s station identifiers for its premiere airdate April 1, 1954: chalk pastels of a TV camera in the shape of the call letters.

WQED President Deborah Acklin has a framed original in her office, which Nathanson sent in time for the station’s 60th anniversary in 2014.

“He also sent something I’d never seen before: the station’s first three program guides, for April, May and June 1954,” Acklin said. “It’s a little treasure trove. You can see they were inventing something; it’s all so new.”

With his gifts, “Norbert helped us piece together a little bit of our history,” Acklin said.

A physical turning point

A central figure in that early history was the young Fred Rogers, who would go on to become a public television icon.

In 1954, Nathanson worked closely with Rogers and Josie Carey; the two puppeteers bubbling over with ideas for their show, The Children’s Corner, which aired live each day. “They had so many things they wanted to do, they didn’t know what to do first,” Nathanson told Current.

Nathanson crafted the three-dimensional castle (complete with rooftop TV antenna) for King Friday, a puppet character brought to life by Fred Rogers. (Photo: Nathanson)

Rogers and Carey worked their puppet magic against a plain gray canvas with holes cut into it for the characters to peek through, Nathanson said. “Josie was in front, and Fred was the puppeteer behind it.”

One day Rogers came in with a small owl character he called X; Carey pointed out that X needed a home. As Nathanson recalled: “She taped an acorn to the canvas and said, ‘Maybe this will grow.’ So that night I snuck in and painted a twig coming out of the acorn. The next morning Josie said, ‘Oh, look, it’s growing!’

“By the end of the week, I’d eventually painted a tree,” he said. “And over that weekend, Roy Nelligan, the only union member and only stagehand at WQED, helped me cut the hole and finish it.”

The two collaborated to create King Friday’s castle and Grandpere’s Eiffel Tower. It was an exciting time: “Nobody knew what would happen next” on that set, Nathanson recalled.

Nathanson also illustrated a 1954 book by Rogers and Carey, Our Small World, an autobiography of characters who would go on to public television fame: Daniel S. Tiger (named after WQED’s original president, Dorothy Daniel), King Friday XIII, Grandpere, Lady Elaine Fairchilde and X the Owl.

Soon the station was going gangbusters, and Nathanson quickly took on more roles: floor manager, station-break director, set designer, producer, announcer “and sometimes cable puller,” as he recalled. In the fall of 1955 alone, Nathanson said, WQED mounted 35 live programs. Within the following 12 months, he worked on:

- Weeklong remote live coverage of the Allegheny County Fair, a public television first;

- A TV pilot for the popular Philadelphia-based America’s Town Meeting of the Air, one of radio’s first public-affairs talk shows, featuring chemist Harold Urey, a Nobel Prize winner in 1934;

- The Duquesne University Opera Workshop’s production of Puccini’s Sister Angelica, directed by renowned Russian conductor Boris Goldovsky;

- Four shows with legendary poet Robert Frost, two in which he spoke with children and two with adults; and

- Looking at Modern Art, a 12-episode series produced by Robert Snyder, winner of the 1950 Oscar for his documentary The Titan: Story of Michelangelo.

All were among the first programs distributed nationally to educational stations, and two instructional series for international use were produced for the U.S. Armed Forces Institute, an educational arm of the Defense Department, Nathanson recalled. In addition, the station broadcast the nation’s first televised high school credit courses, which Nathanson helped direct, and from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. aired daily elementary instructional courses to 60 school districts.

After Nathanson left WQED in 1956, he remained interested in broadcasting “but only worked on the periphery,” he said, largely due to his disability. “I was unable to get another job in the new rapidly expanding noncommercial TV industry, because nobody could get past my appearance,” Nathanson said. Public TV “wasn’t the villain,” he added, “it’s just the way things were.”

Nathanson, right, directs an instructional high school science course for Pittsburgh’s WQED during its first years on the air. (Photo: Nathanson)

Even simple handshakes posed a challenge, as Nathanson didn’t have a right hand. “I developed the practice of quickly extending my left hand, turning it over and grasping the other person’s right hand in a smooth movement that permitted them to cover any unease or embarrassment they might experience,” he said.

That year he spent eight frustrating months job hunting in New York City.

He happened to stop in at New York University, which he heard was working on closed-circuit television projects. There Nathanson discovered that the producer of America’s Town Meeting of the Air was now in charge of NYU’s closed-circuit work. “He knew what I could do,” Nathanson said, and soon he was hired as an adjunct.

For his master’s degree, which he obtained while teaching at NYU, Nathanson created several short programs about teaching deaf children through television that caught the attention of the Eisenhower administration. He later joined the federal Captioned Film offices in Washington, D.C., which provided subtitled movies to deaf organizations nationwide.

But during his time in the capital, Nathanson struggled with ongoing physical pain and mental anguish. “The nature of my disabilities with my lower legs was such that when I walked I was very visible,” he told Current. “My unusual gait was distorted and attracted attention. And it looked as though I couldn’t do things that I actually could.”

As a person with a disability, Nathnson said, he encountered complex challenges beyond his physical problems. “If you have a disability and write a letter of application for a job, do you mention it? If you mention it, chances are you’ll get no response. If you don’t, what happens when they first see you? It’s a very difficult thing that people with disabilities experience.”

By 1960, he reached a crossroads with his disability. In a journal entry dated Nov. 5 of that year, Nathanson wrote that he had a chance to walk more easily and live pain-free, but only if he had both legs amputated just below the knees.

“The quid pro quo is, very simply, the traumatic experience of surgical amputation vs. the will to function and appear normal,” he noted in the entry. “The former is something no rational person approaches without some degree of trepidation; the latter something no disabled person does not dream about.”

Nathanson agreed to the surgery, and the amputations were performed the next month. He was fitted with prosthetic legs.

“Things became much easier for me physically,” Nathanson told Current. “I no longer attracted the attention I did previously. I appeared, if you’ll excuse the expression, ‘normal.’”

Following his surgery and recovery, in 1964, Nathanson went on to work at the New York Department of Education’s Bureau of Communications. “In the early days of public broadcasting, states were putting together networks and associations,” Nathanson said. Local organizations applied to states for seed capital to establish stations; he assisted in the process of getting them on the air.

“We were instrumental in overseeing the development of several individual stations” during his two-year tenure, he said, including WNET, WXXI in Rochester and WNED in Buffalo.

His dreams of a family life also came true; he married in 1964 and fathered two children.

In 1977, Nathanson began work at WMHT-TV as a consultant, which evolved into a full-time position as director of program development, generating content ideas and securing production grants. It became his “dream job” as director of television activity: “I administered a staff of some 20 persons: producers, directors, cameramen, technical directors and performers.”

Nathanson soon became the station’s executive producer. He’s especially proud of All in a Lifetime, a series of four documentaries about people of various ages with disabilities. One film won honors in the annual media awards of the California Governor’s Committee on Employment of the Handicapped in June 1984. Nathanson calls the project “my public coming out” as an amputee, because he served as host and interviewer.

He left the station later that year; a heart attack soon curtailed his professional life.

Now Nathanson, who turns 87 in November, is well settled into retirement in Northport, Maine. He’s still involved in teaching through the Maine Senior College Network, which provides non-credit courses for adults over the age of 50. He also enjoys gardening and fishing.

As he said, “It’s been an interesting, although difficult, life.”

This article was first published in Current, Sept. 9, 2013.

WQED I remember them for Mr. Rogers Neighborhood.