Getler to measure PBS journalism against its goals

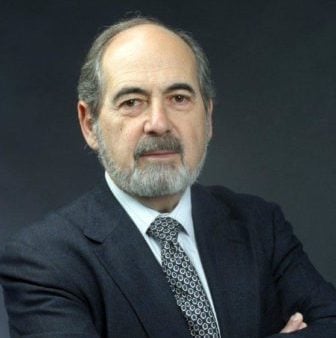

For the first time PBS has hired a journalist to critique the programs it distributes — veteran newspaperman and departing Washington Post Ombudsman Michael Getler.

Getler will report to PBS President Pat Mitchell but has autonomy in examining

the editorial integrity of PBS programs after broadcast.

“The contract is ironclad in terms of having complete independence and lack of interference,” Getler said. The ombudsman’s charter “goes to the journalistic mission of PBS and how it measures up to its own standards,” he said. The goal is “to try to keep it as good as it can be.”

Getler’s two-year contract begins Nov. 15.

The appointment is PBS’s latest move to reinforce its editorial standards after a string of controversies over programs, including its long-running dispute with former CPB Board Chairman Kenneth Tomlinson over Now with Bill Moyers, a news program branded as liberal commentary by Tomlinson and some others.

In January, David Brancaccio took over as host of Now, but lingering disagreements over the show — and two others that CPB funded to bring more conservatives to PBS’s air — blew up into a full-scale public dispute this spring over politicization in program decisions.

Like NPR and CPB, PBS now has its own in-house critic to respond to complaints about journalistic integrity and fairness.

Unlike ombudsmen at NPR or newspapers, Getler will be advising a distribution organization with limited and indirect supervision of journalists. Producers of PBS programs work at public TV stations and independent companies.

PBS began weighing whether to establish an ombudsman’s office more than a year ago and studied the role of ombudsmen at NPR and the Canadian Broadcasting Corp., Mitchell said. In June, the journalists and station execs on PBS’s Editorial Standards Review Committee recommended hiring an internal critic as part of its thrust to be more transparent and responsive to the public.

“One of the reasons I supported this idea was that it puts someone at PBS who can respond meaningfully to communications from the public,” said Carl Stern, a former NBC News correspondent who teaches journalism ethics at George Washington University. PBS traditionally refers viewers with complaints to program producers. “That seems like a bit of a dodge — like passing the buck,” he said.

The PBS committee also updated PBS’s editorial policies and published its report on PBS.org.

Getler first met with Mitchell in July to discuss the job, not knowing that she was interested in hiring him. “I have my hands full at the Post and was not aware of PBS’s internal goings-on,” he said. “It’s a terrific new challenge and I was available because my Post contract was coming to an end.”

“I was especially impressed by his thoughtfulness and journalistic credentials,” Mitchell said of that first meeting. “I thought it would be really good for the enterprise to have someone with his experience as a public editor but extensive journalistic credibility.”

Getler became ombudsman at the Washington Post in 2000 after spending most of his career as a Post correspondent and editor. He joined the newspaper as a military affairs reporter in 1970 and covered central and Eastern Europe as a foreign correspondent during the Cold War. He was assigned as the Post’s national security correspondent in 1980 and London correspondent in 1984. He later became the Post’s foreign editor and assistant managing editor for foreign news.

In 1993, Getler was promoted to deputy managing editor. He left the Post in 1996 to become executive editor of the International Herald Tribune, which was then jointly owned by the Post and the New York Times.

“He is a serious, highly principled and motivated journalist,” Stern said. “Having someone like that in-house should prove to be of value to the management of PBS.”

“He’s very down-to-earth and doesn’t hold back,” said Tony Barbieri, a former Baltimore Sun correspondent and editor who now teaches at the University of Maryland. He admires Getler’s work as the Post’s ombudsman.

“Those jobs are very hard to do because you’re writing about your colleagues’ work,” Barbieri said. “He’s very honest and doesn’t flinch from saying what needs to be said.”