A moral transaction

This essay appeared in the Washington Post June 21, 2005, after Bill Moyers retired from hosting the PBS weekly public affairs program.

I must be the luckiest man in television for having been a part of the public broadcasting community for over half my life. I was present at the creation. As a 30-year-old White House policy assistant in 1964, I attended the first meeting at the Office of Education to discuss the potential of “educational television,” which in turn led to the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. When I left the White House that year to become publisher of Newsday, I did fundraising chores for Channel Thirteen in New York and appeared on its local newscasts. Then in 1971, through a series of serendipitous events, I came to public television as the correspondent and anchor for a new weekly series called This Week.

I must be the luckiest man in television for having been a part of the public broadcasting community for over half my life. I was present at the creation. As a 30-year-old White House policy assistant in 1964, I attended the first meeting at the Office of Education to discuss the potential of “educational television,” which in turn led to the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. When I left the White House that year to become publisher of Newsday, I did fundraising chores for Channel Thirteen in New York and appeared on its local newscasts. Then in 1971, through a series of serendipitous events, I came to public television as the correspondent and anchor for a new weekly series called This Week.

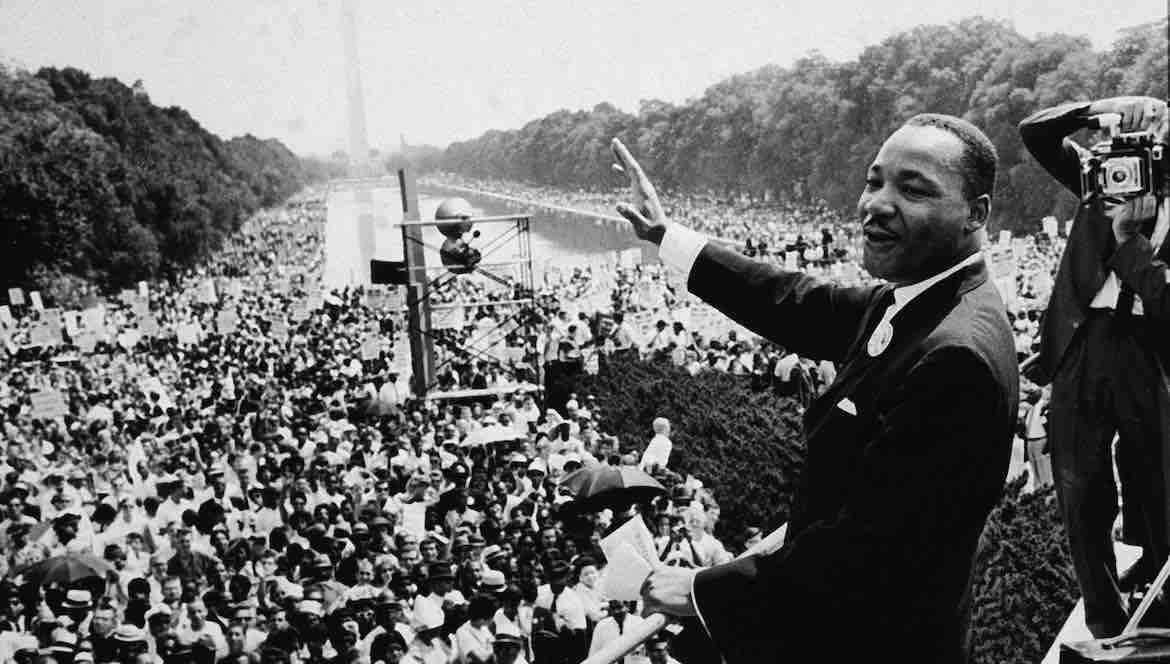

Moyers in a 2012 appearance on ‘The Tavis Smiley Show.’

Now, a quarter of a century and countless broadcasts later—from Creativity and A Walk Through The Twentieth Century to Six Great Ideas With Mortimer Adler and Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth, from Amazing Grace and All Our Children to The Language of Life and Fooling With Words, from The Secret Government and The Wisdom of Faith to Genesis, America’s First River, Becoming American, On Our Own Terms, Close to Home, Trading Democracy and Now with Bill Moyers — I am mindful of what William Temple meant when he said that a person whose life is given to a purpose big enough “to claim the allegiance of all his faculties and rich enough to exercise them is the nearest approach in human experience to the realization of eternity.”

Public television has provided me such moments, as well as colleagues and kindred spirits who have inspired and nurtured my aspirations — among them Fred Rogers and Big Bird, Fred Wiseman and Ken Burns, Robert MacNeil and David Fanning, Julia Child and Alistair Cooke. I am, of course, just one fish in the ocean of public television.

This is a big, sprawling, polymorphic community: in our best days an extended family; in our worst days, a dysfunctional one. Right now, however, we’re facing some hard choices. Competitive forces are razing the landscape around us and turf wars are breaking out the way they once did between sheepherders and cattlemen. Funds for new programming are hard to come by. And fevered agents of an angry ideology wage war on all things public, including public broadcasting.

All this tumult swirls around a public television community that if not divided is certainly not wholly united in sympathy and aspiration. That’s nothing new. In the first speech I made to the Friends of Channel Thirteen back in 1969, I found myself recalling how George Washington had described the new United States of America created by the Constitutional Convention: “It was for a long time doubtful whether we were to survive as an independent republic, or decline … into insignificant and withered fragments of empire.” The same could be said of public television. From the womb, we seemed offspring of the Hatfields and McCoys.

There is no unanimity now over how public television should respond to the rapid changes occurring in telecommunications; there are differences among us over governance; we don’t see eye to eye on the mission and role of PBS, station representation in the decision-making process, the responsibilities of membership, the balance between local and national, or the question of back-end rights; we can’t even agree on what constitutes core programming. Anyone who proposes solutions for public television winds up with critics on all points of the compass.

Perhaps it’s the nature of things; a creative community is no respecter of conformity. But I know that the ultimate measure of any system, any society, or any institution is not how it acts in moments of comfort and convenience but how it responds to challenge and controversy.

The best thing we have going for us is a strong and consistent constituency. Millions of Americans look to us as the best alternative to commercial broadcasting, and even when we let them down, they seem to keep the faith and grant us a second chance. Deep down, the public harbors an intuitive understanding that for all the flaws of public television; our fundamental assumptions come down on their side, and on the side of democracy.

What are those assumptions?

- That public television is an open classroom for people who believe in lifelong learning..

- That the medium can dignify life instead of debase it.

- That it can help us to see more clearly, understand more deeply, and laugh more joyously.

- That human creativity and this incredible technology can provide us with a fuller awareness of the wonder and the variety of the arts and sciences, of scholarship and craftsmanship and innovation, of politics and government and economics and religion and all those mutual endeavors that shape our consciousness.

- That commercial broadcasting, having made its peace with “the little lies and fantasies that are the by-products of the merchandising process,” is too firmly fixed within the rules of the economic game to rise more than occasionally above the lowest common denominator.

- That Americans are citizens and not just consumers; in the words of the educator Herbert Kohl, “if we do not provide time for the consideration of people and events in depth, we may end up training another generation of TV adults who know what kind of toilet paper to buy, who know how to argue and humiliate others, but who are thoroughly incapable of discussing, much less dealing with, the major social and economic problems that are tearing America apart.”

Those of us who helped launch public broadcasting were not disdainful of commercial television. We ourselves tuned to it for news, diversion and amusement. We knew that it helped to keep the economy dynamic through the satisfaction or creation of appetites. We are a capitalist society, after all. The market is a cornucopia of goods and services, and television programs are part of that market. There is always something to sell, and television can sell.

But public television was meant to do what the market will not do. From the outset we believed there should be one channel not only free of commercials but from commercial values; a channel that does not represent an economic exploitation of life; whose purpose is not to please as many consumers as possible, in order to get as much advertising as possible, in order to sell as many products as possible; one channel — at least one — whose success is measured not by the numbers who watch but by the imprint left on those who do.

I keep on my desk a report delivered a few years ago by Gale Metzger of Statistical Research. It found that:

- When people look for a program on science or the arts, or a program their children can watch, they look first to public television.

- We rated higher with people who want to understand issues that are important to society.

- Two-thirds of the people see our news and public affairs as a mixture of political persuasions—they think we are fair.

- As for the charge of elitism, public television rated about the same with people who have a high school education or less as with people who have college degree or higher.

- Most important, two out of three people said it would make a difference to their lives if public television did not exist.

During the bicentennial of the Constitution in 1987 my associates and I produced a series about the significance of the Constitution in contemporary life. Several members of the Supreme Court participated as well as legal scholars, historians, philosophers and regular citizens whose defense of their First Amendment Rights had taken them all the way to the highest court in the land. Among the letters we received was one from a housewife in Utah:

I have never written a letter like this before. I am a full-time wife and mother of four children under seven years and I am entirely busy with the ordinary things of family life. However, I want to thank you very much for In Search of the Constitution. As a result of this series, I am awakened to a deep appreciation of many ideals vital to our democracy. I am much moved by the experience of listening at the feet of thoughtful citizens, justices and philosophers of substance.

These are people with whom I will never converse on my own, and I am grateful to you for having brought these conversations within my sphere. I am aware that I lack eloquence to express the measure of my heart’s gratitude. I can say, however, that these programs are a landmark among my life’s experiences. Among all the things I must teach my children, a healthy interest in understanding the Constitution now ranks very prominently. Thank you.

After all these years, I am convinced that public television could yet be the core curriculum of the American experience. E.D. Hirsch in Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know lamented that our schools no longer are teaching young people the essential ingredients of a general education. “To grasp the words on a page,” he said, “we have to know a lot of information that isn’t on the page.” He called this knowledge “cultural literacy,” and described it as “that network of information all competent readers possess.”

It’s what enables us to read a book or an article with an adequate level of comprehension, getting the point, grasping the implications, reaching conclusions: our common information. Some people criticized Hirsch on grounds that teaching the traditional literature culture means teaching elitist information. That is an illusion, he says; literature culture is the most democratic culture in our land; it excludes nobody; it cuts across generations and social groups and classes; it’s what every American needs to know, not only because knowing it is a good thing but also because other people know it, too.

This was the Founders’ idea of an informed citizenry: that people in a democracy can be entrusted to decide all-important matters for themselves because they can communicate and deliberate with one another. “Economic issues can be discussed in public. The moral dilemmas of new medical knowledge can be weighed. The broad implications of technological change can become subjects of informed public disclosure,” writes Hirsch. We might even begin to understand how—and for whom—politics really works.

A few years ago, we produced a special on money and politics. We showed how private money continues to drive public policy and how our campaigns have become auctions instead of elections. As the broadcast came to a close, we put on the screen the 800 number of a non-partisan group called Project Vote Smart. When you call the number, they send you a printout showing the campaign donors to every representative in Congress. In response to that one broadcast, almost 30,000 Americans got up from their chairs and couches, went over to their phones and dialed the number!

But informing citizens is not all we’re about.

Americans are assaulted on every front today by what the scholar Cleanth Brooks called “the bastard muses”:

- propaganda, which pleads, sometimes unscrupulously, for a special cause at the expense of the total truth;

- sentimentality, which works up emotional responses unwarranted by and in excess of the occasion;

- pornography, which focuses on one powerful drive at the expense of the total human personality.

About that time, Newsweek reported on “the appalling accretion” of violent entertainment that “permeates Americans’ life — an unprecedented flood of mass-produced and mass-consumed carnage masquerading as amusement and threatening to erode the psychological and moral boundary between real life and make-believe.”

How do we counter it? Not with censorship, which is always counterproductive in a democracy, but with an alternative strategy of affirmation. Public broadcasting is part of that strategy. We are free to regard human beings as more than mere appetites and America as more than an economic machine.

Leo Strauss once wrote, “Liberal education is liberation from vulgarity.” He reminded us that the Greek word for vulgarity is apeirokalia , the lack of experience in things beautiful. A liberal education supplies us with that experience and nurtures the moral imagination. I believe a liberal education is what we’re about. Performing arts, good conversation, history, travel, nature, critical documentaries, public affairs, children’s programs—at their best, they open us to other lives and other realms of knowing.

The ancient Israelites had a word for it: hochma, the science of the heart. Intelligence, feeling and perception combine to inform your own story, to draw others into a shared narrative, and to make of our experience here together a victory of the deepest moral feeling of sympathy, understanding and affection. This is the moral imagination that opens us to the reality of other people’s lives. When Lear cried out on the heath to Gloucester, “You see how this world goes,” Gloucester, who was blind, answered, “I see it feelingly.”

When we succeed at this kind of programming, the public square is a little less polluted, a little less vulgar and our common habitat a little more hospitable. That is why we must keep trying our best. There are people waiting to give us an hour of their life —time they never get back—provided we give them something of value in return. This makes of our mission a moral transaction. Henry Thoreau got it right: “To affect the quality of the day, is the highest of the arts.”