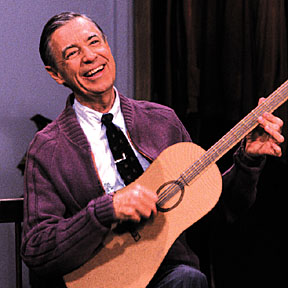

Fred Rogers: ‘No matter where he was, a lot of love came through’

Fred Rogers occupied a quiet corner of the tumultuous television landscape, but his influence was profound and borne of the kindness, love and honesty he inspired in people.

Richard Kelly

Ministering to kids’ emotional lives, Roger and his message of self-love and compassion endured beyond the tot years.

Witness the outpouring of tributes and condolences since Rogers’ death Feb. 27. The media overflowed with lengthy obituaries and heartfelt tributes. Preschoolers from a Montessori school in Cincinnati expressed their love for the PBS program host by carrying a handmade banner to public TV station WCET. Mourners as different as rock musicians at San Francisco’s Noise Pop Music Festival and sports-talk provocateurs on the syndicated Tony Bruno Show lamented Rogers’ passing. A trolley service in Harrisburg, Pa., gave free rides to children and collected donations for the memorial Fred Rogers Fund.

Last week, the House of Representatives unanimously resolved to honor Rogers for his “steadfast commitment to demonstrating the power of compassion and his dedication to spreading kindness through example.”

“This is not just about Fred’s death,” said Hedda Sharapan, spokeswoman for Family Communications Inc., the nonprofit that produces Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. “We all long for that goodness, and we it to continue.”

“If we ever needed Fred Rogers and his spirit, I think the world really needs it now,” said Donna Mitroff, a Los Angeles-based former television executive who worked with Rogers at WQED in Pittsburgh. The 35-year national run of his program is a testament to the universality of his approach. “There’s something there that made that happen in a world where things don’t sustain very long. He was answering some very, very deep generational need.”

Rickey Brown

Rogers and two of TV’s other big fans of childhood — Art Linkletter and Bill Cosby — served as grand marshals of the Tournament of Roses Parade, Jan. 1, 2003.

Rogers, 74, died after a brief battle with stomach cancer. His staff learned of his illness in January, just before he underwent surgery.

“He spent weeks at the hospital,” said Sam Newbury, production director. “We all hoped that he would get better, but he didn’t.” Rogers spent his last days at home with his family, “which was what he wanted.” He was buried in a small private ceremony March 1.

Family Communications ended production of new episodes two years ago, but PBS stations continue daily broadcasts of the series that in 1968 became public TV’s first nationally distributed children’s program.

The company, headquartered at WQED in Pittsburgh, is board-controlled, and its staff continues to create grant-funded workshops and training programs that serve children, families and caregivers.

Those who worked with Rogers came to embrace his philosophy and mission and plan to carry it on, said producer Margaret Whitmer. “You realize when you’re making good television that you’re doing something with your life that is definitely worthwhile. Even though it’s not your vision, you can carry it on. I feel like it’s really important to continue this work, and to try to be the best I can.”

Conflict: neither exploited nor avoided

Fred McFeely Rogers decided to pursue a career in television after being appalled by a pie-in-the-face shtick he saw on early children’s TV. He decided he could do better. Late in life, he regularly encouraged media professionals to use their talents for high purposes. “We can either choose to use the powerful tool of television to demean human life or we can use it to enrich it,” he said in 1999 when inducted into the Broadcasting Hall of Fame.

His audience on that star-filled night included Saturday Night Live talent there to honor another inductee, SNL creator and executive producer Lorne Michaels, recalled Mitroff, but Rogers seemed to make the more lasting impression. “As he always did, he had us on our knees. I’ll never forget seeing such jaded people who couldn’t contain themselves with the truth and goodness that Fred stood for.”

He also received two Peabody Awards, four Emmys, and — just last summer — the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Rogers began his television career in 1951 at NBC, a college grad with a music degree who worked his way up from gofer to floor manager. He moved back to Pittsburgh two years later to help launch WQED. One of the programs he developed and produced was The Children’s Corner, a live hourlong series featuring short children’s films and Josie Carey, his first creative collaborator, interacting with Rogers’ puppets. “They soon found that what they were giving children during the fill was more important than the films,” Sharapan said.

During the seven-year run of The Children’s Corner, Rogers studied child development under leading child psychologist Margaret McFarland. He also attended the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. When he was ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1962, he was given the special mission of serving children and families through media.

McFarland, who died in 1988, advised Rogers for 30 years as he carried out his unique ministry. As the principal educational consultant on the series, she met with Rogers for two hours every week, “helping him understand the background of what he was dealing with,” said Sharapan, also a student of McFarland.

Another key influence was Fred Rainsberry, creator of the Canadian Broadcasting Corp.’s children’s service. He recruited Rogers to Toronto in 1963 and told Rogers he had a natural rapport with children and should be on camera. Rogers reluctantly agreed and came out from behind the scenes in the 15-minute series Misterrogers.

He moved his young family back to Pittsburgh a year later and returned to WQED where he created a half-hour show that included the CBC segments. Eastern Educational Network distributed the shows until 1968, when National Educational Television raised foundation money to offer Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood nationally.

“We were able to give him color monitors and a color set,” said Paul Taff, former Connecticut Public Broadcasting president who laid the groundwork for the series’ national launch while working at NET. “That was the turning point.”

Child development theories that tended to preschoolers’ social and emotional needs shaped Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. He spoke into the camera as if addressing a single young viewer and paced the conversation so the child watching could talk back to him. He helped his young viewers differentiate between the modest real-world set that he inhabited with the neighborhood of make-believe—where his puppet characters worked out conflicts in imaginative minidramas.

“Rather than say, ‘You should share,’ it’s more helpful to kids to see puppets working it out,” commented Frances Stott, dean of academic programs at Chicago’s Erikson Institute, a child development graduate school. “It’s a more indirect and powerful way of learning.”

The opening sequence, in which Rogers changed from world-of-work clothes into a comfy sweater and sneakers, gave each program a predictability young children found reassuring. These routines also helped them anticipate sequences of events and learn to control their impulses, observed Stott.

But the most important element of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was the attention Rogers paid to children’s emotional lives, she noted. During his television visits and with his songs, he conveyed self-affirming messages such as “my feelings are important,” “I’m special just the way I am,” and “there are people who are fancy on the outside and fancy on the inside.”

“I love that he gave permission for negative emotions,” Stott added. “That is critical.” Anger, sadness, jealousy and selfishness are “part of the lives of children.” Rogers also dared to deal with topics other children’s programs wouldn’t touch—divorce, death, disability and racial differences. He encouraged children to think about how they felt about these things and always reassured them, Stott noted.

More often he spoke of the joys in life. He introduced children to musicians, actors and Koko the gorilla. He took viewers on field trips to beaches and toy factories.

When programs dealing with difficult subjects aired, they didn’t provoke an immediate response, but their effect accumulated over time, recalled Kitmer. “We found out anecdotally through fan mail.” FCI would hear from people who were abused as children and wrote to say, “Mister Rogers was the only person who made me feel good about myself.”

Children’s television researcher Dorothy Singer recalled when Rogers appeared at Yale University and football players skipped practice to meet him for tea. During another campus event, students filled the hall to sing along with him to “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” and “You Are Special.” They told him how his programs helped them deal with the big and small traumas of childhood.

Singer recalled being stunned by the reaction. “No matter where he was, a lot of love came through,” she added. “He was as genuine in person as he was on the air.”

“It’s hard to say ‘was,’ because I keep thinking of him all the time.”

Kidvid you could aspire to do

“I definitely think that he changed the way television had been created,” said Angela Santomero, co-creator and executive producer of Nickelodeon’s Blues Clues and a lifelong fan of Fred Rogers. “His show was a window to the world in the sense that it took television for kids, made it smart and something that you could aspire to do.”

The sincerity and genuineness with which he spoke to people made them believe that they were special, she added. “Those messages are hard to quantify. The reason it’s so powerful is that it’s missing in family life.” When she was a tot, Santomero talked to Rogers on the TV screen. In the eighth grade she wrote that she wanted to be Mister Rogers in a career aspiration essay.

Rogers’ influence extended into creation of Blues Clues, she acknowledged. Actors preparing for host roles are given Rogers’ books and encouraged to watch Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. The manner in which Rogers speaks to children and his pacing have influenced producers of other children’s shows, including the Disney Channel’s Bear in the Big Blue House.

Barney & Friends adopted Rogers’ focus on social learning, albeit with a faster pace, noted Singer. Like Mister Rogers, Barney has been criticized for being “too sweet, too nice and too loving,” she said, but that is a strong point of both programs. Children who develop firm, trusting bonds as tots are better able to cope with problems that come up later.

Although the programs live on in PBS broadcasts, Rogers’ unique approach is unlikely to be replicated in today’s commercialized children’s market. Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood never relied on international sales and licensing revenues to fund production, and its whole-child approach to its audience sets it far apart from today’s pack of preschool shows.

Most producers focus largely on cognitive development and literacy and not enough on the social and emotional lives of young children, Stott said. “Learning to handle emotions, being able to share and have friends, being able to deal with separation—these are not trivial things” and are easily as important as knowing the alphabet, she said.

“Before a child has the assignment of knowing what the letters ‘C,’ ‘A’ and ‘T’ represent, my desire is to be able to have that child see as many different kinds of cat and feel what a cat’s fur feels like, and know that cats have their own feelings,” Rogers said in a 1996 Current interview. “I want them to get as large an interior view of a cat as possible until it’s narrowed down into three letters on a page.”

“I came along at a time when people could accept the kind of thing that I was ready to give for children,” Rogers told television critics during a 1998 press tour appearance. “I translated my own feelings and understanding of childhood to what this new medium was.”

I loved Mr. Rogers so much. I aspire to be like him in word and deed.