‘The difference is that public TV serves a country, not a market’

Some say that the advent of new media — in particular, the challenge of cable television — has decreased the need for public broadcasting and its partial federal support. The opposite is true. Such suggestions miss the point of public television’s enduring potential. Our opportunities to serve the American public are growing as a result of changes in the broadcasting environment. We should welcome discussions of public broadcasting, with the confidence that a clearer understanding of our purpose, and perhaps some adjustments of our structure or tasks, will strengthen our service. If anything, the need for public television and federal support of it is stronger now than in 1967, when the Public Broadcasting Act was passed.

It should be noted that federal support is not the heart of public television: member support is. Federal money makes up about 17 percent of total public TV revenues. In 1990, individuals contributed to public TV stations a larger percentage of revenues — 22 percent — than any other category of supporter.

Public television originally was conceived as a voice of quality in what former FCC Chairman Newton Minow called “a vast wasteland.” For the third of us who do not have or cannot afford cable, including many with the greatest need for educational programs, broadcast television is even less distinguished than it was then.

For viewers with access to many channels, television may not be a wasteland, but it is a thick jungle of largely undistinguished programs. To be heard in a noisy jungle, one needs to have a distinctive voice. Public television has that voice.

Personally, I have never felt that “noncommercial” is a good adjective to apply to public broadcasting. We raise most of our money from noncommercial sources, but an important part of our financing comes from corporate underwriting. And at least some of a corporation’s desire to identify itself on public television comes from what anyone would consider a commercial motivation.

So what makes public broadcasting “public”? Is it just a matter of degree? Is it just “less commercial” than other television? Is commercial television just “less public” because it airs high-quality programs less often and interrupts them with commercials instead of running underwriter credits at beginning and end?

I think the answer to this question, and the key to the purpose of public broadcasting, relates to the difference between a country and a market.

The geographic United States and its population are a market. So is every other place and people. But we are also — very importantly for those of us who live here — a country. I think we all understand the difference.

A country is a body politic and a culture that, if successful, enables a people to make good collective decisions, express their purposes, share some common values, protect themselves, develop to their full potential, and enhance their lives.

“Markets” are vigorous, challenging, flexible and ultimately truthful. Their ability to learn, react and satisfy inspires admiration. But markets have no thoughts, values or higher purposes beyond their reflexive response to needs. Few people have knowingly fought or died for a market.

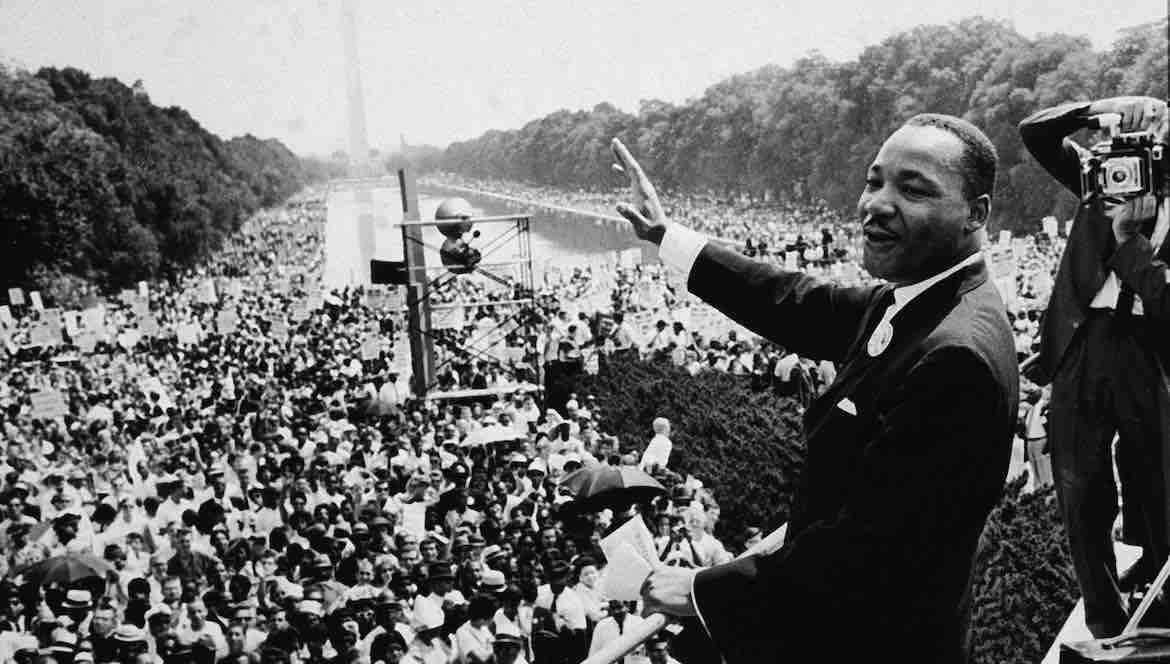

A people needs to nurture those things that help it be a country. Common experiences, such as wars, elections, art, music, drama and sports events are examples of things that help us to be country-like. A common language and a common analogy base, rooted in knowledge of the shared history and literature that define us, are critical to our ability to discuss issues and make decisions as a body politic.

We are not thrown into as much oral communication as we once were. Newspapers, town meetings, neighborhood bars and even schools have faded in quality or importance for this purpose. For good or ill, most Americans today rely on television as their principal source of information about their country, other Americans and subcultures with which they have little contact. They also rely on television for knowledge of their leaders and potential leaders, for most of the theater and opera they will see, for too much of the American history and literature they will learn and for much of the information, education and individual expectations that help us work as a country.

Only public television — non-market-driven television, excellence-driven television — has as its sole purpose the education and development of the American community. Public television’s best programs such as The Civil War, MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, Sesame Street and Eyes on the Prize, exemplify its service commitment and raise the hurdle for our performance in the future.

These lofty ambitions, and public TV’s acceptance of federal funds, are great responsibilities, with great obligations. Public television must never be “government” television. It must never sacrifice its quality or educational goals to build audience numbers. It must never become a service available only to those who can afford cable or direct satellite services. It must not narrow the breadth of opinion it expresses or of financial support it receives. It must not advocate, even by implication, positions on partisan political issues, and must be equally accessible to the broad spectrum of mainstream political views. It must always work hard to preserve the characteristics that made it “public.”