Alliance with pubTV boosts Rhode Island PEG

In the extended public media family, local public stations and operators of public access cable channels have long related to each other like estranged, distant cousins.

In the extended public media family, local public stations and operators of public access cable channels have long related to each other like estranged, distant cousins.

Public TV was the richer, more connected and widely recognized outlet for professionally produced community-based nonprofit media; public access was where volunteers could pick up media production skills creating shows that had little chance of being seen outside of their communities.

Public TV projected an air of elitism and high culture; cable access was of the people, where no-frills telecasts of government meetings coexisted with wackier fare. Their funding and governance structures were completely different, and there was little if any reason for public TV and public access to collaborate.

But as digital technology reshapes the media landscape and exposes gaps in local news and information — and as legacy media outlets like TV stations and cable channels look for new service models — these two members of the public media family may find they have more in common than they thought.

It’s already happened in Rhode Island, where a restructuring of cable regulations in 2006 put the state’s public TV network in charge of public access channels that had been operated by Cox Communications, the dominant cable operator in the state.

Leaders of Rhode Island PBS and Rhode Island Public Access both see benefits from their unusual pairing. The statewide public TV network receives about $200,000 annually for its management oversight and operational support for public access channels. And public access managers say the streamlined management structure and ideological compatibility of working with a public media institution has been a boon.

Rhode Island is a proven example of what can happen when public TV and public access media collaborate, but their merger is not likely to be widely replicated. It came about through a unique set of circumstances that sprang from Rhode Island’s small size and the configurations of its local media. However, pubTV and public access executives say their collaboration provides important lessons for the rest of the public media world.

“I definitely think that public access and public TV have more in common than people think,” said David Piccerelli, president of RI PBS. “The creativity I see and the quality of programs we have on public access are right up there.”

One boss better than many

Rhode Island has only seven active cable service areas, and by the early 2000s Cox Communications had acquired a near monopoly in the state. As per regulations, Cox operated public access studios in each of those seven areas.

When Verizon petitioned to enter the Rhode Island cable market with its fiber-optic technology, legislators faced a conundrum. Under state law, Verizon would have been required to build studios in all of the seven areas, duplicating those already established by Cox. In order to avoid this redundancy, lawmakers changed the rules.

“Basically, in the 2006 legislative session, the legislature amended the laws to give the RI Public Telecommunications Authority [licensee of RI PBS] duties, responsibilities and powers over PEG access,” said Piccerelli. “It permitted the cable companies to no longer be responsible for PEG.” Public access channels are often referred to by the acronym PEG, shorthand for the public access, education and government-information programming that populates its channels.

In February 2007, all 17 of Cox’s PEG employees became staff of the Rhode Island PBS Foundation, the private nonprofit that supports operations of the public TV network. RI PBS acquired all of Cox’s PEG assets and assumed all of its leases when it took over the business of running Rhode Island public access.

According to Elizabeth Esposito, director of RI PEG Access, the restructuring has allowed Rhode Island public access to blossom.

“It’s been a fantastic relationship with PBS,” said Esposito. “It’s not a big cable company with a lot of management, and I think it helps that PBS manages us really well.”

Esposito was employed by Cox in a similar role and found that the cable company’s oversight of PEG Access was often cumbersome, she said. Cable companies still pay the franchising fees that have traditionally financed PEG access operations, but now they have less direct oversight and less ability to make decisions about PEG that are in their own self-interest.

She points to Rhode Island PEG’s state-of-the-art studio in Providence, which opened in February 2010. Under Cox’s management, PEG was housed in aging facilities, and had limited resources for equipment and technology upgrades. Piccerelli encouraged her to develop the new facility, which features two studios, two control rooms, a green room and four editing suites. Its $1 million price tag was completely financed by revenue from cable subscribers.

Esposito likes having one boss instead of many. “I don’t have another manager besides David [Piccerelli],” she said. “It’s a much smaller scale than Cox, and it’s easier to deal with.”

There’s another unique aspect to Rhode Island PEG’s structure. Because the state is so small, all seven of its cable service areas are interconnected. Each area has its own local studios and distinct channels, but three additional “statewide interconnect” channels are available to practically every cable subscriber in the state. This gives many of RI PEG’s top producers the ability to reach a statewide audience.

If Cox and Verizon each maintained their own PEG access channels, then a subscribing household’s channel options would be limited to those operated by their cable provider, Esposito said. “With PBS management, it’s not exclusive to the cable provider, and we have wider reach.”

This distribution system creates the best kind of problem for Esposito: high demand for timeslots among aspiring producers. “On Interconnect B, our general statewide public access channel, we have 10 people waiting for 60-minute timeslots and 15 to 18 people waiting for 30-minute timeslots,” said Esposito. “It’s a lot.”

Similar problems, similar missions

Sylvia Strobel, executive director of the Alliance for Community Media and previously a longtime public broadcaster, sees the Rhode Island restructuring as emblematic of a narrowing gap between public access and public broadcasting nationwide. ACM is a national public access membership and advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C.

“Public access media and public media have many of the same problems, similar missions and are increasingly playing similar roles in their communities,” said Strobel. “Hopefully, we can work together to find answers.”

She hopes that these symmetries will foster more collaboration. “We want to work more closely with public TV and public radio,” said Strobel. “I think the public access stations that are thriving are those who are innovating and making partnerships and collaborations — doing business a little differently.”

Strobel prefers the moniker “community media centers” to describe PEG Access channels because many of ACM’s 300 members have moved beyond TV to produce content for the Web and local radio airwaves, primarily through low-power FM (LPFM) broadcasts.

She pointed to centers in St. Paul, Minn., and Grand Rapids, Mich., as examples of this shift.

The Grand Rapids Community Media Center is housed within a performing arts venue, the Wealthy Theatre, and its TV outlet, GRTV, telecasts many of the theater’s performances. The center also operates WYCE-FM, a volunteer-powered LPFM station that streams its programming online. Its latest innovation is the hyper-local digital news service The Rapidian, which received a grant from the Knight Foundation.

“For a small community, they’ve done an outstanding job of growing their mission and distributing content in many different ways,” Strobel said.

The St. Paul Neighborhood Network (SPNN) also has moved toward a public media service model by developing programs by and about the diverse ethnic communities of St. Paul. Members of the Hmong, Somali and Ethiopian immigrant communities of St. Paul produce SPNN programming, and the center also runs a media training program for youth.

“The media centers that I see succeeding are the centers getting out of the silo mentality and reaching out to their local community, which public access entities are uniquely suited to do,” Strobel said.

“Party on, Wayne”

Live from his parents’ basement in Aurora, Ill., featuring his best friend Garth and proudly telecast on public access TV, the fictional Wayne’s World has probably done more than anything else to create the impression that public access media is the realm of goofballs and wannabes.

The now-classic Saturday Night Live sketch and a 1992 film portray public access TV as indelibly amateurish, perpetually silly and worthy of ridicule.

“That’s the single biggest misconception,” said Piccerelli. “It’s not Wayne’s World. It’s not that at all.”

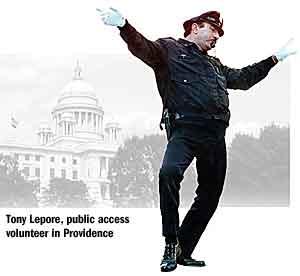

In Rhode Island, public access producers John Carlevale and Tony Lepore exemplify the distinct flavor of public access in the Ocean State. Both pushed past the Wayne’s World caricature toward professional standards that allow them to build collaborations, win awards and get noticed.

Carlevale is a 68-year-old retired college professor and longtime producer of State of the State, a weekly public access talk show. He’s also one of Rhode Island PEG’s most enthusiastic boosters and innovators.

Carlevale is a 68-year-old retired college professor and longtime producer of State of the State, a weekly public access talk show. He’s also one of Rhode Island PEG’s most enthusiastic boosters and innovators.

“I think RI PEG Access is a fabulous program,” said Carlevale. “I could not say anything negative about the program, even if a gun was held to my head.”

Carlevale has been producing State of the State for 20 years, with the goal of “helping citizens better understand the government.” Elected officials appear regularly as his guests, and the show is produced out of RI PEG’s new Providence studio. Since 2001, Carlevale has produced State of the State with financial support from Operation Clean Government, a nonprofit nonpartisan advocacy organization.

After retiring from the Providence Police Department, Tony Lepore turned to cable access stardom as Tony “The Dancing Cop,” a children’s TV character he plays with aplomb. His public access TV show, Safe Kids & Friends, is one of Rhode Island Public Access’ biggest successes.

“My forte as a policeman was directing traffic, but I always wanted to be a performer,” Lepore said. Since 2005, he has produced a new episode of Safe Kids & Friends roughly each month. The children’s show promotes safety, good behavior, responsibility and health. Lepore writes, produces and performs the show through his company, Dancing Cop Enterprises. Each monthly taping draws dozens of kids as his studio audience.

Lepore has taken his dancing cop act on the Rosie O’Donnell Show, Good Morning America, and Today and even to Texas Motor Speedway for a NASCAR race.

“The show is a lot of work,” said Lepore. “I just really wanted create a safe haven for children. Why not have a show where children can watch, but also come in and be in our audience? To boot, it’s also good for the community.”

“Public access is diverse, and I love that,” Carlevale said. “Diverse in terms of subject matter, and also diverse in the sense that the little guy gets as much opportunity to make his case as the big guy.”

Both Lepore’s and Carlevale’s shows are recipients of multiple Rhode Island PEG Awards. The awards, an annual Oscar-like ceremony that honors the best of public access, draw hundreds of attendees every year and are fiercely competitive. Both Lepore and Carlevale also enjoy being recognized on the street, which happens with some frequency.

“I mean this in the best possible way, but it is somewhat cult-like,” said Piccerelli. “There is a huge following of public access programming here in Rhode Island.”

RELATED LINKS

Website of Tony Lepore, Rhode Island’s Dancing Cop.

The Rapidian of Grand Rapids, Mich.

St. Paul Neighborhood Network of St. Paul, Minn.

In Vermont, the Bennington Banner reports on CAT-TV’s 20th anniversary

Extensive Wikipedia list of PEG access organizations in the U.S.

Alliance for Community Media, the association of PEG access units.