Why WNET backed away from groundbreaking coverage of the Chile coup

WNET

Grainy television title card with blurred city buildings and hills in the background. White block text across the center reads: “CHILE: A SPECIAL REPORT.”

On Sept. 11, 1973, a military junta seized power in Chile.

A month later, WNET/Channel 13 was promoting what it billed as “American television’s first in-depth profile” of the coup. The one-hour “Chile: A Special Report” aired Monday, Oct. 15, with a rerun scheduled for that Thursday.

But within hours of the initial broadcast, the rerun had been canceled. Viewers who contacted the station learned the startling news from the WNET librarian: The Chile special had been erased.

This was the beginning of an intractable myth. For decades, even those who worked on the Chile special believed that it was gone.

A few years ago, filmmaker Christina DiPasquale was conducting archival research at WNET about Realidades, the first national bilingual television series in the U.S. “Chile: A Special Report” was an episode of this show. When she dug up the old Realidades episodes in the WNET archives, DiPasquale uncovered the lost Chile special.

Thanks to her initiative, the American Archive of Public Broadcasting has made the documentary available for online streaming. But there has yet been no reckoning with what happened.

“Chile: A Special Report” called out the new military junta for its “fascist-like ideology” and highlighted American involvement in the destabilization of Chile. Why did WNET pull it from the air?

José García and ‘Realidades‘

In 1972, José García, a 33-year-old Puerto Rican filmmaker from Spanish Harlem, filmed the pilot for a new Latino-centric public affairs show for WNET. Ana María García (no relation), a filmmaker and retired professor of the Universidad de Puerto Rico, said, “He was a totally anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist filmmaker. I think that is the core of who he was and at the core of his work.”

For the pilot, García used the classic play La Carreta to show both the hopes and broken dreams of Puerto Ricans coming to the big city, but WNET refused to air it — it was “too down,” García later recalled. In response, the local Puerto Rican community protested at the station, demanding that WNET represent New York’s 20% Latino population with its programming. The community ultimately negotiated with WNET President John Jay Iselin to create Realidades, which launched in October 1972 with Humberto Cintrón as EP and García as producer. (DiPasquale will tell that story in her film Barrio Television, now in mid-production.)

While the Realidades team was breaking ground with its bilingual coverage, a broader battle was afoot regarding the direction of and funding for public broadcasting. As the Ford Foundation stepped down its grants to make way for federal funds, the Nixon administration took on a pitched battle against public television. Nixon vetoed the 1972 Public Broadcasting Bill that would have provided long-term funding. Then, in January 1973, the CPB Board — influenced by Nixon — canceled several public affairs programs. Iselin was tasked with saving WNET.

That August, the Realidades budget was cut by two-thirds — an “existential-level cut,” DiPasquale said.

In September, García directed “Chile: A Special Report.” With scant days and a meager budget, he rushed to assemble a show on a topic that even commercial networks hadn’t yet touched. By November, he had been fired.

The ‘second coming’ of Allende?

The first and only time it aired, “Chile: A Special Report” was preceded by a disclaimer delivered by Frederick M. Bohen, director of news and public affairs for WNET. Previously employed by the Ford Foundation, Bohen had come to WNET in March of 1973 and was described by the New York Times as “somewhat square but tough.” In his disclaimer, Bohen emphasized the station’s commitment to fairness and balance, and promised a follow-up special that would address other views on Chile. He was already guarding against backlash.

The first half of the documentary, narrated by García, shared a brief history of workers’ movements in Chile, from the beginning of the 20th century to Allende’s years in office. The footage concluded with the Sept. 11 bombing of La Moneda, the seat of the Chilean government.

The coup footage was not being shown in Chile. Viewers residing abroad — starting with those in Uruguay — were able to see precisely what Chileans could not, according to Marcelo Morales, director of Chile’s national film archive. Furthermore, in the days after the coup, only foreign correspondents risked filming such events as the book burnings that are shown in “Chile: A Special Report.” Footage captured in Chile typically had to be smuggled into Argentina before being sent abroad, usually to Europe. Tricontinental Film Center, which distributed militant Latin American films during this period, provided some of the historical footage used in the Chile special, with footage from the coup coming from news feeds, according to center co-founder Rodolfo Broullon.

Throughout the narrative, García focused on the exploitation of Chile’s natural resources and people by foreign corporations, as well as Allende’s promise to free his country from foreign interference. He foregrounded Allende’s accusations that the American companies Kennecott Copper and ITT were interfering in Chilean affairs. In an interview with Massachusetts Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, García asked whether the Senate would investigate these corporations.

Bohen tried to pull the editorial perspective in the other direction to reveal Allende’s shortcomings. He asked García to show the women who banged pots to protest Allende. García — perhaps in a tongue-in-cheek response to his English-speaking boss — included scenes of these women chanting protest songs riddled with Chilean swear words. Against Bohen’s recommendation, García charged the Chilean military with perpetrating the “bloodiest massacre in the modern history of Latin America.”

DiPasquale noted, “José was refusing to try to create this false equivalence between the democratically elected government and what he knew was a violent military regime.”

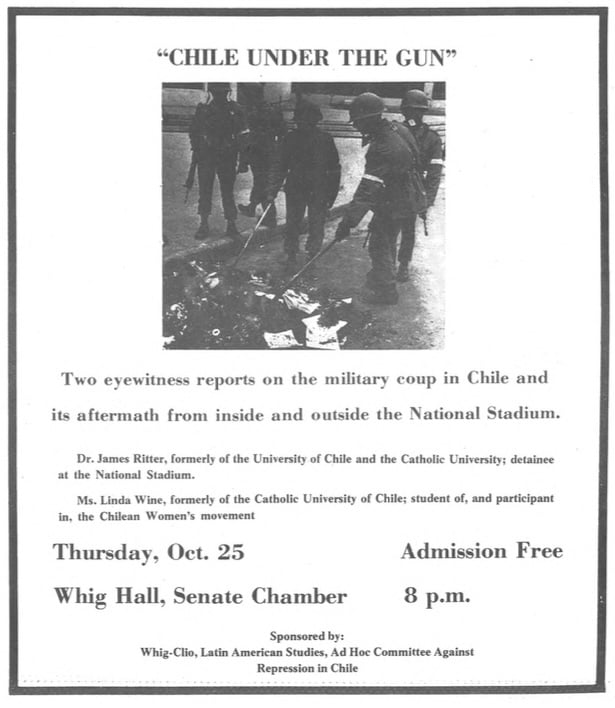

The second half of the Chile special featured a discussion guided by New York Times contributor José Yglesias. The participants included Andrés Rojas-Wainer, the former press attaché for the Chilean Embassy in Washington; the Rev. William Wipfler, director of the Caribbean and Latin American Department for the National Council of Churches; and Jim Ritter, an American professor who had lived in Santiago and worked at the Universidad de Chile and the Universidad Católica. He had been detained and beaten at the infamous National Stadium shortly after the coup.

To give the junta’s perspective, James Holger agreed to participate. Holger was the new chargé d’affaires of the Chilean mission to the United Nations; the permanent representative had just resigned. But Holger was a no-show for the taping.

Having him as a junta stand-in was essential for Bohen, who was pushing García to create more “balance.”

“I insisted on going ahead with it,” García said in a 2000 interview, “placing an empty chair with the name of the junta’s representative in his place.”

The Chile special aired, disclaimer and all. Consequences for García were swift. García, who had been performing contract work for Realidades, was dismissed. Humberto Cintrón fought to keep García, going above Bohen’s head to make his case. But not only was García’s career at WNET finished, he was also let go from his teaching position at the State University of New York Old Westbury. He later claimed this was due to his being labeled a Communist. (I reached out to SUNY, but employment records from that time are not available.)

Looking back in a 1990 CENTRO interview, García said, “I was very naive.”

He soon left for Puerto Rico. Working on Realidades had changed him. Though he once went by the Americanized name “Joe Garces,” he now used his own name and would go on to become fluent in Spanish as he continued his work as a filmmaker. In 1985, he joined co-founders from across Latin America in creating La Fundación del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano, a Cuba-based organization originally presided over by Gabriel García Márquez and dedicated to championing Latin American cinema. Ana María García, a fellow co-founder, described José García as a “pioneer of Puerto Rican film, especially in New York through his work in Realidades.”

In an email exchange with me, Rodolfo Broullon, who is credited as a contributing producer in the documentary, shared, “José was very courageous in pursuing an independent point of view in tackling this project. WNET’s execs called it ‘the second coming of Allende’ after firing him.”

WNET’s explanation for the debacle was simple and consistent: García’s work did not meet their journalistic standards. But was that the whole story?

The controversy

With his shoestring budget and small crew of Realidades staff and freelancers, García shared a message at odds with the powerful currents of mainstream media. Before the coup — as Margaret Power, professor of history emerita at Illinois Tech, has written — the media had portrayed Allende and the Unidad Popular government as victims of their own incompetence. “They labeled them ‘Marxists,’ which in the context of the cold war meant that the public should consider them a threat, undemocratic, and the enemy,” she wrote in her paper on the Chile solidarity movement.

García’s sympathetic portrayal of Allende’s mission and his accusations of American interference provoked viewers. Writing in 1974, Yglesias said, “[I]t received, I understand, the greatest response the station had had in a long time.” Thanks to archivists at the University of Maryland, I reviewed dozens of letters sent by viewers to WNET about “Chile: A Special Report.” Though these only constitute part of the feedback the station received, they illustrate a wide-ranging and intense response.

Most of the letters I reviewed were either explicitly favorable or requesting a rerun as part of what appears to have been a letter-writing campaign. Educators in the tristate area — including faculty from Vassar and Brooklyn College — wrote asking to screen the special for their students.

Chilean viewers were split along political lines. Three employees of LAN Chile, now LATAM Airlines Chile, wrote to praise the special and denounce the junta; they cautioned, “Please do not make public our names.” A woman who identified as a Christian Democrat — a party whose leaders had clashed with Allende and were now being bankrolled by the CIA to justify the coup publicly — lambasted the show.

The most vociferous letters came from critics of Allende. To many, García’s work proved that public media was a left-wing echo chamber. Moved by the prevailing anti-Communist sentiments of the time, they called station staff “Communist bootlickers” and asked if the Chile special came from Cuba, Peking or Moscow. While not speaking for their employers, a few did take care to write in on their corporate letterheads. When it came to substantive criticism, some fact-checked García (at times correctly), and many repeated Bohen’s concerns that the documentary was “not balanced.”

In fact, Accuracy in Media, the conservative media watchdog founded by Reed Irvine in 1969 to fight perceived liberal bias, filed a complaint with the FCC invoking the Fairness Doctrine. WNET insisted that coverage of the coup was not subject to the doctrine because this was “an internal issue for that country [Chile] … not to be construed to be a controversial issue of public importance in a local American broadcast market.” In 1974, the FCC sided with WNET and later denied an appeal by AIM.

WNET’s statement to the FCC is so at odds with reality, it smacks of cowardice. Not only was the city population one-fifth Latino, but New Yorkers had front-row seats to the controversy around Chile. Anti-junta protests and pro-junta benefits cropped up in and around the city. On Sept. 28, 1973, the Weather Underground bombed ITT’s New York offices in retaliation for the company’s involvement in Chile. On Dec. 3, a bomb destroyed the Fifth Avenue office of the U.S. Committee for Justice to Latin American Political Prisoners, which advocated for the Chile solidarity movement. What was happening in Chile was local. But WNET preferred to argue its own irrelevance than stand by García.

“They relied on his vision and his labor to say something bold and then dropped him the moment it became controversial,” DiPasquale said.

Speculating in Variety about the Chile special’s “erasure,” Bill Greeley pointed out that public television received much of its support from the same sources who supported the new junta — the U.S. government, corporations and banks. “Incidentally,” he added, “ITT is on WNET-TV’s ‘Honor Roll’ of contributors.” In reviewing WNET’s archives, DiPasquale discovered that Kennecott Copper had been a donor as well.

It was no secret that ITT had been involved in shady dealings both domestically and internationally. In early 1972, newspaper columnist Jack Anderson broke two major scandals involving ITT. The corporation had donated to the Republican National Convention in exchange for Nixon’s Justice Department settling an antitrust case and had also offered the CIA $1 million to derail the 1970 election of Allende. Nixon was furious with Anderson’s revelations. Anderson not only ended up on the president’s enemies list but was also targeted for assassination.

The question of whether ITT had meddled in public media, especially at a station as significant as WNET, rang alarm bells in the offices of Democratic Rep. Donald MacKay Fraser. With Iselin reading over his shoulder, WNET’s assistant to the general counsel wrote to Fraser that no corporation — including ITT — had contacted the station regarding the documentary.

Given the political and economic context of the time, I am inclined to believe that ITT had no direct hand in the cancellation. As Iselin’s brief but vehement notes to Bohen suggest, WNET leadership perceived the Chile special as a fumble, a bad one, in the battle for financial survival, which was inseparable from the fight against Nixon. Unwilling to defend a show made by an independent filmmaker, WNET relented.

The irony is that such a course correction was fruitless: WNET’s subsequent solicitation for funds from Kennecott Copper and ITT went unanswered.

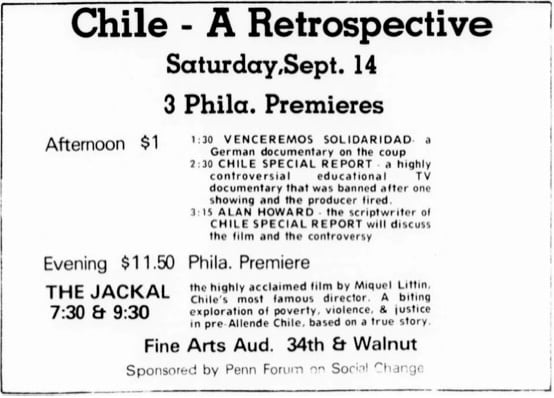

After the initial controversy, WNET made the film available to schools at $35 per copy and even reluctantly licensed it to WTNH-TV in New Haven, Conn., though it’s unclear whether it ever aired. In 1974, the Penn Forum on Social Change, a student-run organization at the University of Pennsylvania, screened the Chile special back-to-back with a discussion with scriptwriter Alan Howard. The first 28 minutes of the documentary were even entered into the 1975 Virgin Islands Film Festival, but it was not shown. Aristides Martínez, the film’s editor, recalls that it was stolen. However, Variety reported that several festival films were in fact lost in transit, suggesting that this particular disappearance was simply a case of bad luck.

‘The Junta Show’

On Oct. 18, WNET’s general counsel advised Bohen that inviting Kennecott Copper and ITT to comment during the follow-up show might help stave off any legal claims. While Bohen weighed what to do, the junta’s perspective was getting plenty of exposure in other news media.

The right-wing Chilean newspaper El Mercurio — which benefited from CIA and ITT funding — printed the junta’s claims for a Chilean audience. Some English-language press distributed that propaganda abroad. Several letters sent to WNET included some variation of the junta’s bogus claim that Allende had armed thousands of foreign extremists living in Chile to topple the government on Sept. 18. The junta seeded this propaganda so well that one Chilean wrote to WNET that his uncle, a senior naval officer, “knows the name of the person who was supposed to kill him.” Two writers explicitly cited The Economist’s Chile coverage as well. I initially thought Robert Moss, their Latin America correspondent, was credulously repeating the junta’s bunk, but historian Alexander Zevin has shown that Moss was in fact working with the CIA.

Meanwhile, no matter his “bias,” García’s accusations had merit. Within a few years, mainstream American media would be echoing his main points: U.S. corporations and the U.S. government had interfered in Chile, as the 1975 Church Committee proved, and the junta that had promised “law and order” was a brutal dictatorship.

The situation in Chile finally kick-started a mainstream conversation about U.S. interference in Latin America. “Up until then, U.S. policy may have been challenged in Vietnam, but it wasn’t really challenged in terms of U.S. imperialism in Latin America,” historian Margaret Power said. “It was Chile that broke through that.” Steve Volk, professor of history emeritus at Oberlin College, added that in the long run, “Chile became extremely important in terms of putting human rights as an international solidarity movement on the map.”

But WNET refused to be part of telling that story.

Carolyn N. Brooks has written that in these early years, public broadcasting would learn lessons that shaped the field for decades, creating a culture at PBS ruled “more by concerns over what could not be aired than what could.” That was already the case at WNET in 1973. As an anonymous source told Variety, “There’s a new lack of courage here and inability to face up to the national and international issues [in the station’s programming].” In 1975, another source informed the New York Times, “We haven’t done anything controversial in two years. The amount of prior restraint within the station is incredible.”

WNET never aired a follow-up special, as Bohen had promised. I imagine that a “junta special” would have been either redundant or even ludicrous, considering how rapidly the junta’s human rights abuses were coming to light. Just four days after the Chile special, the “missing” American Charles Horman was found to have been murdered by the junta.

Fifty years later

Many of those who worked on Realidades and “Chile: A Special Report” have passed away, including José García and Humberto Cintrón. I asked historian Steve Volk about the tension between keeping up the hope that you’ll find answers and accepting that some questions don’t have them. “It’s a contradiction that can’t be solved,” he said.

As a young man, Volk was friends with Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi and later helped their families search for these missing men. “As a historian,” he said, “I know that certain voices don’t make it into the archive. … Some voices will never be resurrected.”

I am a Chilean-American from New Jersey. Over the course of writing this piece, I came to understand that the Puerto Rican community took up the cause of Realidades not just to see themselves represented but also to leave a record. Who gets to be remembered?

Now a retired historian of science, Jim Ritter had not seen the documentary until I contacted him earlier this year. He lives in France, and we connected across time zones over Zoom. Looking back at his 29-year-old self, he remarked to me, “I was struck by what I and the others said in terms of how calm and discussive we were. It wasn’t at all the way I was feeling.” Ritter had been released from detention Sept. 26 with seven other Americans. He had been severely beaten and then given only 48 hours to leave the country with his young son.

“We had just come through it, and it was absolutely…” He paused. “Well.” If not for the coup, Ritter confessed, he might still be living in Chile today.

Seated beside him, Andrés Rojas-Wainer was navigating a life in upheaval. The Washington Post reported in mid-September of 1973 that Rojas-Wainer’s family was drastically downsizing since his resignation as they prepared to live in exile. Rojas-Wainer had requested an armed escort to attend the taping of the Chile special. His concerns were not without merit. Three years after this, his former colleague Orlando Letelier would be assassinated on the streets of Washington, D.C.

Even James Holger, whose absence basically torpedoed the special, had entered choppy waters. He resigned shortly after the special, and Chilean scholars speculate he exited due to tacit disagreement with the junta. He only returned to the foreign service after Pinochet stepped down in 1990.

“I don’t see anything [in WNET’s record] about the gravity, and importance, and risk in capturing that on this television show,” DiPasquale said. “Everything is all about, ‘Why didn’t the junta show up.’ Look at what you have here!” This was a life-altering, grievous moment for the roundtable participants.

Although the Chile special was gone, those involved with the documentary found other ways to protest what was happening in Chile. Jim Ritter spent the following year traveling the States speaking about his experience in Chile. Scriptwriter Alan Howard went on to work for the Chile Solidarity Committee. Wipfler later directed the Human Rights Office of the National Council of Churches. Moderator José Yglesias told the story of the Chile special in the introduction to the 1974 book Chile’s Days of Terror, which also carried a gut-wrenching interview with Ritter. The Chilean folk music group Quilapayún, whose music was used in the Chile special, went into exile in France and continued to perform and protest the coup from abroad. Tricontinental Film Center brought Patricio Guzmán’s monumental indictment of the junta La Batalla de Chile to the United States in 1978.

The Chile special is a record of the many people who cared about, and fought for, a return to democracy in Chile. Given the strong parallels between President Trump’s and Nixon’s approaches to public media and the impending closure of CPB, its story suggests both hard questions and lessons for those working in the field today.

“This accusation of not being objective enough is one that has been used for all the years that people of color have been in newsrooms,” said DiPasquale, who has also worked in media advocacy for Latinos. “Especially in our current information landscape, we really have to look at how these accusations are disproportionately leveled against journalists of color and independent producers of color.”

Public media would not have diversified without relentless pressure from the community, and every win was followed by a challenge. Realidades was canceled in 1974. After another campaign by activists, it returned at a national level in 1975 and ran until 1977. Lillian Jiménez, a former filmmaker and activist who has written about Puerto Rican cinema, has praised DiPasquale’s work in telling that story. “It’s important for young people today facing the onslaught of shock and awe to know that people really resisted at a time when there was less support,” she said. “Historical recuperation is absolutely critical.”

Andrés Rojas-Wainer died in 2011. I spoke with his daughter Alicia, who was a toddler at the time of the coup. Her father had hoped to return to journalism after resigning from the embassy. “In those days, if you were a journalist and you affiliated yourself politically, you found yourself shut out,” Alicia said. “He suffered greatly from the loss of this profession that he valued and cherished.” He eventually found his way into landscape design.

Alicia had not known the Chile special existed until now. “One of the things that was most striking about the film is that I never knew this man who was so confident and so clear about his role, and who had this kind of strength.” She added, “There is something so meaningful about restoring him to his place in history.”

At the time of the Chile special’s airing, no one knew how long the junta would rule. The political polarization, the violence and fear, the unpredictability — these echo contemporary troubles. I am most moved by how time has altered the meaning of this documentary. No longer a call to action, it is a sobering reminder of the many decades of work and patience that justice demands.

When speaking of the Chile special, José García would often mention Jaime Barrios Meza, a Chilean he met and befriended in Puerto Rico. Barrios later became Allende’s economic advisor. While filming “Chile: A Special Report,” García learned that Barrios had been with Allende on Sept. 11. He was detained and killed.

His remains would not be found until 2001. Even then, they were not identified until 2014. By that time, García himself had already been dead for ten years.

Writer’s note

I give immense credit to Christina DiPasquale, who shared her tremendous insight into Realidades, José García and WNET’s corporate sponsors. She also recovered “Chile: A Special Report” from the archives. This article would not have been possible without her desire to see this story come to light.

In addition to those interviewed in this piece, I would like to thank the following people for providing additional guidance, background and resources. They appear here in alphabetical order: Rob Alegre, Jonathan Buchsbaum, Gary Crowdus, Jim Green, Aldo Lauria-Santiago, Marcelo Morales, Yeidy Rivero, Geraldina Rodriguez and Regina Rodríguez Covarrubias. I would also like to thank my local public library, which connected me to rare books and news archives, and the special collections and archives team at the University of Maryland Libraries and the archivist at the Social Welfare History Archives at the University of Minnesota. Thank you to the AAPB for presenting the film on its website (Chile – A Special Report, 1973, Thirteen WNET, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (WGBH and the Library of Congress), Boston and Washington, D.C.).

Gina Isabel Rodriguez is a Chilean-American writer. She is an essayist and fiction writer working on a novel set during the Chilean dictatorship.

This is an amazingly good story. I only wish it wasn’t behind the paywall so it could be shared more widely! :)

Thank you, Current, for publishing this article, and for continuing to bring the hard questions that get at the heart of public media into clear focus. It’s a sobering reminder that what we do on behalf of the public trust is never meant to be easy.