Frank Blythe, broadcaster who directed expansion of programming for Native Americans, dies at 82

Vision Maker Media

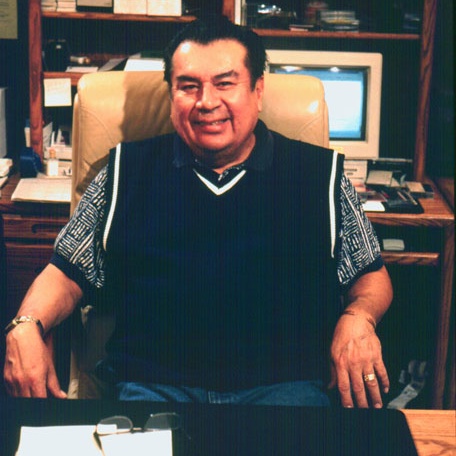

Blythe at the 2021 ceremony for the Frank Blythe Award for Media Excellence.

Francis “Frank” Marion Blythe Jr., founding executive director of the programming consortium that supports public media content for Native Americans, died July 21 at age 82.

His daughter Francene Blythe-Lewis said in a statement that her father passed away peacefully in his sleep. As executive director of Vision Maker Media, Blythe-Lewis now manages the organization her father started and led until his retirement in 2006.

“Native media would not be nearly as far along if it weren’t for Frank’s far-sightedness and his ability to inspire so many others,” said Jaclyn Sallee, CEO of Koahnic Broadcasting Corporation at KNBA in Anchorage, Alaska. Koahnic, a public media organization governed by Alaska Natives, distributes the radio series Native America Calling and National Native News, among others, through its distribution arm Native Voice One.

“One of the most important missions of public television is to tell the whole story of America, and no one told the story of the First Americans better than Frank Blythe,” said America’s Public Television Stations President Pat Butler in a statement. “His contributions to our culture and our understanding of our nation’s history will live forever.”

Blythe was born Nov. 7, 1940, in Pipestone, Minn., to an Eastern Cherokee father and Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota mother, according to an online memorial published by Vision Maker Media. Blythe’s birthplace is the site of the Pipestone quarry, which is a sacred gathering place for Native nations from all around the country.

Blythe’s parents were employed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and worked with boarding schools across the country, according to a 2014 profile of Blythe in Living Well Magazine, a quarterly published by the city government of Lincoln, Neb. Blythe’s family moved to Phoenix when he was around six years old.

Blythe met his wife, Bernice, a member of the Navajo Nation, while pursuing a degree in broadcasting from Arizona State University. After graduating, Blythe worked for a Phoenix radio station, then moved on to Omaha, Neb., for a job as a disc jockey at KOOO. Blythe told Living Well that his on-air persona was “Frank Lee the Cherokee Chief.” While in Omaha, Blythe was recruited by KAET-TV, now known as Arizona PBS, to return to Phoenix.

When leaders from KAET and other stations began planning how to better serve Native American and Indigenous audiences, Blythe participated in the discussions. That was because in 1972 he was one of the few Indigenous people working in public media, according to a 2021 article in The Cherokee One Feather.

“They put us in a room and told us to come out with a mission, organizational structure and a plan,” Blythe told the publication. “We had no experience in organizing anything other than our own projects.”

Out of those conversations, the Native American Public Broadcasting Consortium launched as a startup in 1976 with support from CPB. It later established its headquarters at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln. The consortium was the first of five separate consortia founded to support content by and for minority groups that were underrepresented in public media. These organizations, many of which have changed their names, now make up the National Multicultural Alliance.

At NAPBC, as the consortium was named at its founding, “I ended up being the executive director … mainly because I was the only one that applied,” said Blythe, in the Current podcast Made Possible By … in 2018.

During his years in the job, Blythe struggled to find and maintain funding while navigating what he called a “complicated system” of nonprofit media, he told Living Well. But the organization started to make headway when it collaborated with American Experience for the 1992 documentary In the White Man’s Image, an award-winning film written and produced by Christine Lesiak. The documentary examines attempts to forcibly assimilate Native Americans into white culture through a prison education program created by Richard Henry Pratt, a military officer. The AmEx documentary “was a nice feather in our cap starting out,” Blythe said in Living Well.

Blythe also played a key role in the 1994 launch of American Indian Radio on Satellite, or AIROS, a national distributor of Native American programs such as Native American Calling and Native Sounds Native Voices. Later, Blythe assisted in establishing the Native Radio Network that’s now operated by Native Public Media in Flagstaff, Ariz.

As NAPBC’s program activities evolved, the organization changed its name. During the AIROS era it operated as Native American Public Telecommunications. Later, the name changed to Vision Maker Media. Following his retirement, Vision Maker Media created the Frank Blythe Award for Media Excellence to honor advocates for Native content on public media.

“I think of the powerful stories that would not have been told if Vision Maker Media weren’t around,” said Laura Hunter, a board member for Vision Maker Media and COO for Utah Education and Telehealth Network, in a statement. “Mr. Blythe’s legacy for Native filmmakers and storytellers, as well as public media viewers across the country, is quite remarkable. We’re lucky to have benefited from his work. Knowing it continues with his daughter Francene Blythe-Lewis at the helm should be assuring to all of us in the public media family.”

CPB President Pat Harrison recalled Blythe as “a visionary leader who was proud of his Native American heritage and who elevated and shared authentic stories of Native American culture.”

Blythe-Lewis told Current that her father was an avid reader, particularly of history. Telling his children bedtime stories was one of his favorite activities. He also enjoyed taking his grandchildren and great-grandchildren to movies.

“He was a die-hard Nebraska Cornhusker football fan since 1976. He annually bought his season tickets for two, and took his sons when they were young, then his grandchildren, and his great-grandchildren to the home games,” Blythe-Lewis said. “Even when Nebraska played ASU one year, Frank and [Bernice] sat on the ASU side at Sun Devil Stadium as alumni, but he kept cheering for the Huskers anyway decked in his ASU colors. He had the same two Husker seats for decades and was friends with those who sat around him.”

In his retirement, Blythe was an avid golfer and taught the sport to his daughter and grandchildren. He also loved to host Sunday barbecues and serve grilled vegetables plucked from his garden.

In the Living Well profile, Blythe offered this advice to younger generations: “Find your passion and see if you have the talent to do it. Don’t give up unless you try, because you’ll never know what could be unless you try. You’ll enjoy what you do as long as you have passion. Passion gives you ambition.”

Blythe is survived by his wife of 61 years, Bernice; three children, Francene, Joe and Francis Blythe III; six grandchildren; and six great grandchildren.

A funeral mass of Christian burial for Blythe was held July 27 at North American Martyrs Catholic Church in Lincoln, Neb. Memorials can be sent to the Butherus, Maser & Love Funeral Home and Vision Maker Media.