Documentary ‘ode’ to Steve Post’s many talents leaves out key verses

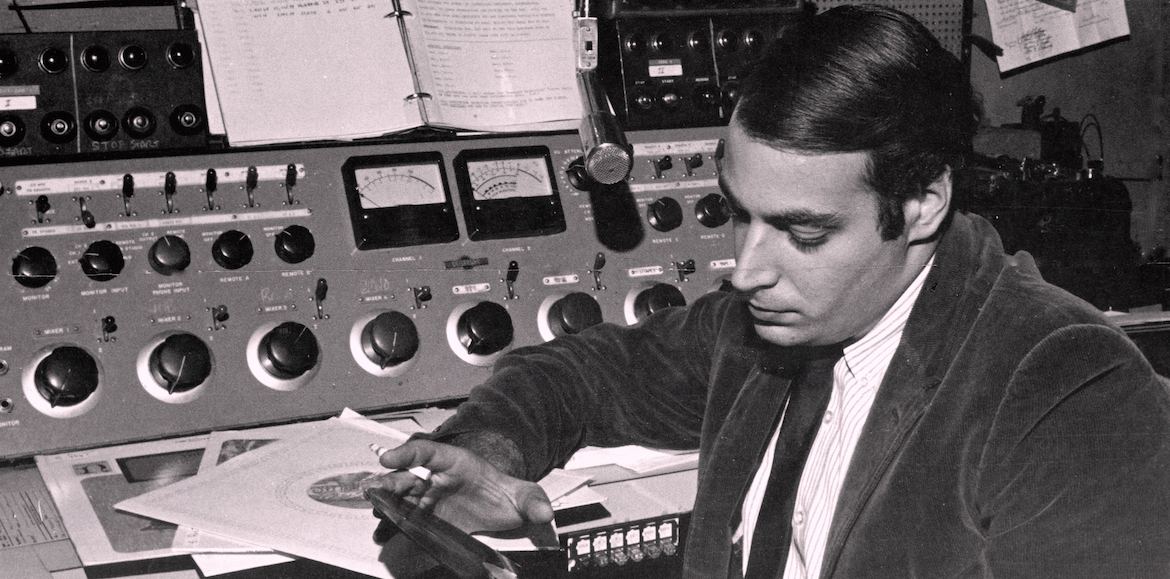

Courtesy “Playing in the FM Band: The Steve Post Story”

Steve Post in the master control of WBAI in New York City in the 1960s.

When I began my radio career as a staff reporter at WBAI in New York in the late 1970s, the Pacifica station’s employees sometimes went weeks or months without a paycheck. We put up with not being paid on time because we really believed in the mission of listener-sponsored radio.

Missed paydays became comedic fodder for our wisecracking station manager, Steve Post, who would approach me in the hallway and say, “Kalish, you’re fired! Pick up your desk and clear out your check.”

Post had many talents, but management wasn’t one of them. His true genius was hosting live, freeform radio — programs that mixed commentary, conversations with in-studio guests and callers, and all manner of recordings. The genre, incubated at Pacifica’s KPFA in Berkeley, Calif., and refined at WBAI, is all about spontaneity and freedom. Post’s mastery of a confessional style of freeform broadcasting, coupled with his prowess at on-air fundraising, are two of his enduring legacies.

Another is the deep connection he made with listeners, including me, during his decades on New York City’s airwaves.

After about 15 years at WBAI, Post left the station for a brief and improbable gig doing news at a commercial disco station. Then, to add another measure of weirdness to his resume, he began hosting a classical music show on WNYC. His program replaced Robert Jay Lurtsema’s Morning Pro Musica, which had originated from WGBH in Boston, and he reached a much larger audience on WNYC. For close to 20 years he dished out wisecracks while back-announcing classical music selections and riffing on stories from the New York Times as a “newscast.” His ability to cajole listeners into donating was pivotal to WNYC’s campaign to buy the licenses of its AM and FM signals from the city of New York.

In 2014, the man who so many New York City listeners and radio broadcasters referred to as beloved succumbed to lung cancer. He was 70.

“Steve was a curmudgeon who complained and complained and complained, but underneath it all, he was a real human being and he connected to other people.”

Rosemarie Reed, director, “Playing in the FM Band: The Steve Post Story”

And now comes Playing in the FM Band: The Steve Post Story, a feature-length documentary that aspires to capture his life and career. It’s not a work of journalism. As EP Caryl Ratner put it, “It’s more like a love letter. It’s an ode to a person, a talent, a life force who had great impact publicly on his audience and privately with the people who knew him and loved him. And I count myself among both.”

The film premiered Friday at New York’s revered independent film theater, Film Forum, before a crowd that included many WBAI and WNYC alumni.

Like me, Ratner and the film’s director, Rosemarie Reed, began their radio careers working with Post at WBAI. Ratner started as an announcer and Reed as development director. After Post left WBAI, Reed served two stints as station manager in the 1980s. Frank Millspaugh, a former WBAI station manager who worked with Post at WNYC, is co-producer of the film and also appears in it.

“Steve was a curmudgeon who complained and complained and complained, but underneath it all, he was a real human being and he connected to other people,” Reed told Current in an interview. “He was a real humanitarian.” The director hopes to find a distributor for a national theatrical release and said the film has been submitted to American Masters, the PBS biopic series produced by WNET in New York City.

Playing in the FM Band reminded me of a similarly loving portrayal of Boston’s commercial but highly political FM rock radio station, WBCN. WBCN and The American Revolution was directed by Bill Lichtenstein, who interned at WBCN at age 14 and went on to become a DJ and newscaster at the station. Public radio listeners may remember The Infinite Mind, which Lichtenstein created and served as EP. The show, which focused on neuroscience and mental health, ceased production in 2008.

Both films aim to capture the creativity and cultural impact of FM radio during its formative years. Another thing they have in common is a slightly inaccurate telling of history — perhaps because the filmmakers were a bit too fond of their subjects or too close to the story to fact-check.

WBCN and The American Revolution, for example, cites The Lavender Hour, a program that debuted on WBCN in 1973, as the first radio program produced by and for the gay community. In fact, a producer named Charles Pitts hosted two different gay programs on WBAI between 1968 and 1973.

After the opening credits of Playing in the FM Band, the very first frame displays text claiming that freeform radio was created at WBAI.

In the same way that jazz flourished in New York but historians trace the music’s origins to New Orleans, freeform radio flourished at WBAI, but it was created at KPFA.

Before John Leonard became an esteemed book critic, he hosted Nightsounds, a late-night freeform program on KPFA. Chris Koch, a news producer at KPFA at the time, thinks the program began in late 1960 or early 1961.

“They were amazing programs,” Koch told Current. “John was mixing seemingly unconnected audio bites and commenting about them and weaving them together into a fascinating montage. He did it for a season.”

If producers of Playing in the FM Band had done their homework, they’d know that Larry Josephson, the last surviving WBAI freeform star, recalled what happened after tapes of Nightsounds arrived in the mail at WBAI. During a 2009 memorial for Leonard, Josephson noted that Bob Fass played the tapes on WBAI. Fass, who passed away last year at age 87, is often credited as the father of freeform, but he didn’t create the genre on his own.

Steve Post acknowledged this in his 1974 memoir, Playing in the FM Band, A Personal Account of Free Radio. Post wrote: “Fass was not the first at Pacifica to do a late-night, freeform radio program. It had begun years earlier with Nightsounds.”

“I don’t have any animus towards somebody who wants to make a movie about someone who did something really great. But knowing that it’s that kind of a film helps you as a viewer.”

— Patricia Aufderheide, Center for Media and Social Impact, American University

This being Pacifica history, there is even some controversy over Leonard’s role as the originator of freeform radio. John Whiting, who volunteered at KPFA in the late 1950s, weighs in: “Nightsounds was just a continuation of a sort of freeform radio which had already been indulged in by a couple of people before that.”

Few would dispute that any other practitioners of freeform came close to Fass, Post and Josephson in elevating it.

As a witness to this history whose life and career was shaped by it, I can’t get over the disregard for facts, lack of nuance and the filmmakers’ failure to acknowledge their relationship to the subject. Ratner and Reed disclose their ties to WBAI in the film’s press kit, but those connections are not revealed to viewers. Millspaugh is identified onscreen as a former WBAI manager.

For viewers of films like Playing in the FM Band, it’s helpful to know the relationships of people behind the camera to their subject matter, said Patricia Aufderheide, a communications professor at American University’s School of Communication.

“I think that knowing from what perspective the story is being told … lets you know that [the film] is going to be a fond portrait,” said Aufderheide, who co-authored a 2021 report from the Center for Media and Social Impact decrying a lack of best practices and a code of ethics in documentary filmmaking.

“I don’t have any animus towards somebody who wants to make a movie about someone who did something really great,” Aufderheide said. “But knowing that it’s that kind of a film helps you as a viewer.”

When pressed on the filmmakers’ decision not to disclose their relationships to the subject, Rattner, the EP, would only say that she declined an opportunity to be interviewed for the film.

Riffs on poultry

Playing in the FM Band does an admirable job of capturing a man who was famous for his self-deprecating humor and existential angst. But it zooms in on some odd stuff. Colorful stories and characters from Post’s career are left out, as are significant chapters and turning points.

Director Reed was obviously taken with one of Post’s WBAI rants about a telephone order to the Chicken Delight chain. So she filmed three people chowing down on fried chicken; and, for some reason, Chicken Delight’s CEO appears, saying she was honored that a radio icon like Steve Post would riff on a bucket of poultry. Was that an editorial decision or satire?

Animation has almost become de rigueur in documentaries these days, so I can understand the decision to animate Post’s telling of his near-death experience while on the air at WNYC. Post had locked himself in a bathroom while a CD was playing and crawled out on a 25th-floor ledge of the municipal building to get back into the studio. But why animate Post’s recollection of his father’s disastrous effort at cooking meatloaf? The film explores how Post’s Jewish grandmother pressured him to eat, but the treatment is clichéd. The segment concludes with movie footage of Jews in biblical Egypt over the song “They Tried To Kill Us (We Survived, Let’s Eat).” Pleeeease.

I question the decision to mix music under an archival recording of Post improvising with two of the 1960s greatest satirists: Paul Krassner, editor of The Realist, and Marshall Efron, the actor and humorist who appeared on the satirical PBS series The Great American Dream Machine. The material stands on its own.

Krassner and Efron were frequent guests on The Outside, which Post began on WBAI in 1965. One night, Krassner was in master control with Post, and Efron joined via telephone claiming to be an Indian guru. Reed mixed flute music underneath Efron’s guru shtick.

During a Q&A after the Film Forum screening, Marc Fisher, Washington Post senior editor and author of Something in the Air: Radio, Rock and The Revolution That Shaped a Generation, commented on how a satirical sketch that relied on cultural stereotyping would never air today.

Those of us who loved listening to Steve Post on the radio savored the impact of his talking directly to us, usually without anything mixed under his voice. And yet more than half of Post’s live radio shtick in the film has music or sound effects added — or both. Anyone who wants to listen to unaltered recordings of Post’s programs for WBAI and WNYC can find both on a new Internet Archive web page that includes shows from as far back as the 1960s.

“It’s not a radio show, it’s a film. It’s a different medium,” Reed said. “And different creative aspects become involved. So I wasn’t presenting it only as how he did it on the radio.” Reed tapped David Amram, another frequent guest on WBAI, to compose original music for the film.

She expects criticism for omitting two of Post’s more outrageous WBAI guests, the performance artist Brother Theodore and the Enema Lady, an anonymous caller who extolled the joys and benefits of — well, you get the picture. Some of Post’s listeners found the Enema Lady so objectionable they canceled their subscriptions to the station and complained to the FCC, according to his memoir.

Post’s widow, Laura Rosenberg Post, called leaving out Brother Theodore and the Enema Lady “ridiculous.”

“I said to myself, I’m going to leave things out. I have to,” Reed said. “I took what was representational, what transferred today as funny or poignant.”

That apparently meant leaving out some of the funniest stories about Post’s escapades that were known to friends and colleagues, like the time he drove across the country in 1976 with one of his ’BAI buddies. The third passenger in Post’s little Honda was a pet monkey named Samba who went swimming with her human pals at a pet-friendly motel in Las Vegas. Rosenberg Post said he told stories about the monkey on the air.

And like what Post did after WBAI missed a grant application deadline in 1979. Post, who was managing the station at that time, decided to fly a station volunteer down to Washington, D.C., with the tardy application. Posing as an employee of the nearby Russian embassy, the volunteer walked into the CPB office carrying the application in an envelope. In a phony Russian accent, the volunteer explained that the envelope had been mistakenly delivered to the embassy. The CPB receptionist must have deemed his accent and excuses credible because WBAI ended up getting the grant, according to Mike Feder, then assistant manager of WBAI.

Nobody could pitch like Post

A 2014 obituary in the New York Daily News by David Hinckley remarked that for almost 50 years, “Steve Post grumbled over the radio so eloquently that it became high art.” There was also an eloquence to Post’s pitching during pledge drives and, often, moments of hilarity.

In the late 1960s Post traveled to other Pacifica stations to help raise money on the air. “They sent him in like a weapon because he was the best fundraiser,” said Rosenberg Post.

According to Millspaugh, in 1967 Post did a freeform show on KPFK, and he taught KPFK staffers how to raise money on the air while he was there. The following year Post went to Boston, where WBUR became the first of 18 Pacifica affiliates.

Will Lewis, WBUR’s GM at the time, said Post shared his on-air fundraising techniques with him and a handful of staffers for one of the station’s very first pledge drives. “We started raising money right away,” recalled Lewis, now 90. When Lewis moved on to KPFK and KCRW in Santa Monica, Calif., he used what he’d learned from Post.

Post’s fundraising chops were a significant factor in WNYC’s decision to hire him, according to Millspaugh, who was a consultant to the station in 1979, when WNYC won a seven-figure CPB major market grant. Millspaugh recalled telling WNYC’s management: “The guy you want for on-air fundraising is Steve Post because he’s the best.”

“Steve was a phenomenal money-raiser,” recalled Mary Daly, PD of WNYC’s AM and FM stations in the early 1980s. “He was effective at telling people why public radio was good and congratulating them for listening.”

In the film, former New York Public Radio CEO Laura Walker credits Post for his fundraising on behalf of WNYC’s campaign to buy its independence from the city government. After Mayor Rudolph Giuliani threatened to auction the licenses of WNYC FM and AM, NYPR, the newly formed nonprofit, paid $20 million over seven years to take over ownership of the stations. Some of Post’s WNYC colleagues were bemused by the zeal in which he greeted the task of asking listeners to subscribe.

Brian Lehrer, who has hosted a daily public affairs show on WNYC for more than 30 years, remembers feeling starstruck when he started working with Post during pledge drives. Lehrer, who appeared in the film and also talked with me, recalled how Post repeatedly played “Pachelbel’s Canon,” a popular classical piece used at weddings, to motivate listeners to call in and subscribe. The technique was rolled out decades earlier at WBAI, where a record of Kate Smith singing “God Bless America” went on autoplay.

Post would also “fake-insult the listener as part of the theater of what he was doing,” Lehrer said in an interview. He also got away with mocking program sponsors and his superiors at the station.

When Post read underwriting copy, “you could hear in his voice what he thought about it. It would make you laugh,” said Karen Frillmann, an editor who started working at WNYC in 1979. “Post wasn’t just a hired voice. He was absolutely himself. That’s what made him beloved.”

‘Genuinely himself’

At WBAI Post helped initiate the tradition of baring your soul on the air. His influence on Mike Feder, the WBAI assistant manager, was profound. Feder produced the freeform show Hard Work. In one of his confessional broadcasts, Feder announced that, after an affair with a listener, he was leaving his wife and kids to go live with his new love.

I wondered whether Post had an impact on other Pacifica live radio hosts, particularly the several New Yorkers who listened to him before moving to the Bay Area in the late 1960s and working at KPFA. The closest any of them came to acknowledging Post’s influence was Larry Bensky, who anchored Pacifica’s coverage of political conventions and managed KPFA in the mid-1970s. “Steve Post was genuinely himself, and I took inspiration from that,” Bensky said.

“My sense is that Steve Post’s approach to radio was so personal and unique to him that it was hard to duplicate anywhere else,” said Matthew Lasar, author of two books on Pacifica history and co-founder of the Radio Survivor blog.

The producers of Playing in the FM Band do describe the toll cancer took on Post’s health. The film notes that he developed the same intestinal cancer that took his mother’s life, at the same age she was diagnosed with it. But Post survived the disease. A lifelong smoker, Post didn’t survive lung cancer.

But they left out the sad chapter of Post’s final weeks and months on the air at WNYC. In the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks, the station’s pivot toward more news and information programming triggered the scrapping of Post’s music show while he was out on medical leave.

After he returned to work in the summer of 2002, Post was given an hourlong weekly live radio program, The No Show. It wasn’t freeform radio, but he did it for nearly seven years.

As his medical treatment dragged on, listeners couldn’t help but notice that Post’s speech became slurred, the result of his medications. Because of Post’s difficulty speaking live on the air, WNYC began prerecording the program, said Millspaugh, producer of The No Show.

“I knew he was running out of steam,” he recalled.

WNYC’s Chief Programmer Dean Cappello pulled the plug on The No Show in March 2009, and Steve Post’s radio career was over.

Director Rosemarie Reed said she didn’t want to dwell on how it ended.

“What would be the purpose of that?” said Reed. “It wasn’t my story.”

I’m identified as a “volunteer at KPFA in the 1930s”, but that was before I became Production Director and a program producer and then London Correspondent for Pacifica Radio, all extending over a twenty year period. It’s all here: http://www.kpfahistory.info/

I thought I remembered Kate Smith singing “When the Moon Comes Over the Mountain” about twenty times, but the memory plays tricks. I think the target was $500.