Lacy coaxes creative talents to share stories of their lives

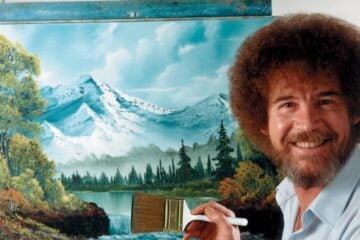

Mel Brooks, pictured during filming of “History of the World: Part I,” put Lacy off when she first asked about participating in a biography. Fifteen years later, “Mel Brooks: Make a Noise” debuts on American Masters May 20. Johnny Carson, below, wouldn’t consent to be featured, but a posthumous film on his life aired last year. (Photos: Pamela Barkentin Blackburn and Carson Entertainment Group)

Susan Lacy is surrounded by lists: lists of actors, lists of musicians, lists of photographers, lists of artists. Lists of architects, lists of dancers.

She has kept and updated these lists for more than a quarter of a century, ever since she began working on American Masters, the PBS biographical series produced at New York’s WNET.

Each list names the top 15 artists in a particular discipline of the arts, such as photography. “If you’re going to make a book on the 15 most important American photographers, who would they be?” Lacy asks herself. (She no longer counts Edward Curtis, Richard Avedon, Annie Leibovitz and Alfred Stieglitz, all of whom have been profiled.)

“I do that with every discipline,” Lacy, founding executive producer of the series, told Current. “When it comes to music, the list is huge because there’s classical, there’s rock, there’s jazz, there’s blues. Even rap. I’m thinking of doing something on that because we need to stay current. And movies. Those are the two longest lists.”

Writing down names is just the first step. It can take years to get the artist to consent to a profile.

Mel Brooks, pictured during filming of History of the World: Part I, put Lacy off when she first asked about participating in a biography. Fifteen years later, “Mel Brooks: Make a Noise” debuts on American Masters May 20. (Photo: Pamela Barkentin Blackburn)

“I started asking Mel Brooks 15 years ago,” Lacy said of the comedian and producer to be featured on American Masters May 20. “He was never ready.” Avedon wouldn’t consider it until after he turned 70. “It took 10 years of monthly phone calls to get Bob Dylan,” she said.

Famously private late-night-TV host Johnny Carson would not consent to be featured as long as he was alive. His posthumous film, broadcast in May 2012, was seen by more than 10 million viewers during the week of its premiere, setting a record for the series.

Asked earlier this year why he finally relented, Brooks pointed to the release of a new boxed DVD set of his films. (His short-lived TV series, When Things Were Rotten, also is coming out on DVD.) And then he pointed to Lacy.

“This woman has given us a treasure trove of the lives of really valuable, wonderful people, and we should be indebted to her,” he said.

Next season, the 28th for American Masters, will include the series’ 200th profile, a biography of the reclusive American author J.D. Salinger. Collectively, those who have been featured constitute an American cultural hall of fame.

That was the whole idea behind American Masters. From the beginning, Lacy set out to build a library of America’s cultural history, a goal that required her to mount high-quality productions in sufficient quantity to make an impact.

Johnny Carson wouldn’t consent to be featured, but a posthumous film on his life aired last year. (Photo: Carson Entertainment Group)

“I could have made my life a lot easier,” Lacy said. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been told, ‘Just do two big films a year. Just do two Dylans a year.’ Nope — won’t do it.”

She aims to show American culture in all its breadth and variety. “I want to make sure every season has diversity in it,” she said. “I want to make sure it has women . . . . I want racial diversity. It’s really important that it not be all white guys.” If you think that’s easy, she said, just try to come up with a female counterpart to Frank Lloyd Wright.

Along with towering cultural figures, there have been lesser-known subjects, such as mambo king Cachao, artist Isamu Noguchi, screenwriter Waldo Salt and choreographer Alwin Nikolais. “I know everybody wishes there could be Johnny Carson every month, but I felt it was important that the series reflect the entirety of American cultural history and that it include writers, painters, architects, playwrights and composers, not just movie stars and pop stars,” Lacy said.

Although it’s now a mainstay of the PBS lineup, American Masters was not initially an easy sell on public television. “Nobody thought there’d be an audience for it,” Lacy said. When American Masters premiered in June 1986, such films were done on the cheap and scheduled at off hours. “It was a self-fulfilling prophecy,” she said.

Lacy’s idea was to make the profiles more like movies. “These are dramatic stories,” she said. “I think the stories of artists are incredible — people who have created something out of nothing, who in many cases are changing the game, creating a new art form. They’re fighting old traditions. They’re forging ahead. They’ve got demons galore. What could be more powerful than those stories?”

Twenty-four Emmys and 12 Peabodys later, Lacy enjoys a reputation for being fair and thorough. Philip Roth, for example, said American Masters was one of the few TV shows he watches.

Filmmaker Robert Weide said he sold Woody Allen on a biographical film by pitching it as an American Masters episode. When funding shriveled during production, Weide raised the possibility of going elsewhere with the film. Allen’s response, according to Weide: “No, no. If we can do this for American Masters, okay. But don’t be shopping it around.”

Record and film producer David Geffen, a media recluse who nonetheless agreed to be profiled, said he, too, is a fan of the series. Among his favorites were episodes on Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins. “I saw the Jerome Robbins film 10 times,” he told TV critics last year. “So when she called up and said she wanted to do one on me, I was flattered.”

Geffen, pictured in 1972, was flattered to be profiled by American Masters, but Lacy warned him going in that it wasn’t going to be a “valentine.” (Photo: Joel Bernstein)

People who are profiled sign agreements to sit for at least four interviews and to cede full editorial control to the producer. The artist also agrees to turn over photos, videos, diaries and journals, and publicly approve the project. Without that blessing, some colleagues would decline to be interviewed.

Lacy warned Geffen, known for his combative tendencies, that the film would reflect a range of opinions about him. “And he said ‘okay,’ and didn’t see the film until it was finished,” she said.

“There’s a chapter in there about how, if you’re not his friend you might as well kill yourself. There’s a part in there about how he sued Neil Young. I sat with him at screenings and, every time those things were coming, I’d watch him get tense. But he’s a big man and he understood from the beginning that it wasn’t going to be a valentine.”

Added Lacy: “Did I say I’m going to deal with every ruthless thing this guy did? No. Why would I do that? Why would anyone ever say ‘Yes’ to us again if our intention was to slam them? The series would have been off the air in three years. But I do make a real effort to be honest, to make an honest assessment of someone and to deal with the ups and downs of their career.”

But longevity and an earned reputation for producing high-quality films hasn’t put American Masters on solid financial footing. Its funding outlook year to year is anything but assured.

The average American Masters bio costs slightly more than $1 million to produce, and PBS pays about that amount annually for eight films. Lacy leverages that PBS money with grants and co-productions deals.

As a rule, the biggest films, such as those on Geffen, Carson, Brooks and Allen, are produced in-house. The episode on the Doors, however, was a co-production with Dick Wolf. “I’m always interested in a co-production if there’s a good team and somebody’s already raised a bunch of money,” Lacy said.

For the right subject — playwright August Wilson, for example — it’s possible to get a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. There’s a long application process that involves hiring scholars to justify the request. “You can’t go to NEH with Mel Brooks, but we’ve done pretty well and they make significant grants.”

The National Endowment for the Arts used to be a reliable source of grants until the agency, squeezed by cutbacks and new priorities for funding digital media, reduced its annual support to the series from $500,000 to $100,000. Corporate underwriting has been scarce, Lacy said. She’s had more luck raising money from individuals and foundations.

It would have been easier to stick to films about movie stars, Lacy says, but she has insisted on representing American art and culture in all its diversity. (Photo: Lorella Zanetti)

In a few cases, particularly when the American Master is also a citizen of the world, the series can sell off international distribution and DVD rights. John Lennon’s bio “LENNONYC,” brought in $800,000 in advances, Lacy said. “When we did Dylan, we had $3.5 million in advance. That was a big, expensive film. Our budgets are high and I don’t say that proudly. If I could do them for less, I would.”

It wasn’t until years after American Masters launched as a PBS series that Lacy began cultivating new revenue streams through licensing deals. “In the beginning years, I didn’t understand anything about rights. We just made the films and got them on the air by the skin of our teeth,” she said. Producers cleared rights to distribute American Masters programs only on public TV in the United States.

“After about the sixth year, I said ‘This is stupid. We have to start clearing other rights,’” Lacy said. “From that point on, we’ve been trying to clear as much as we can.”

On occasion, the subject of a film offered to help with production costs. “I’m not going to tell you names but there have been a few who said, ‘I’ll pay for it.’ I had to tell them, ‘We can’t do that,’” Lacy said.