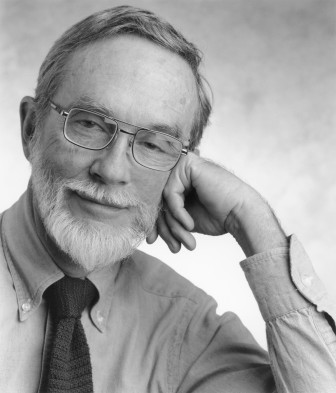

At 90, pubradio pioneer upholds a literary tradition

WPR/UW-Madison Archives

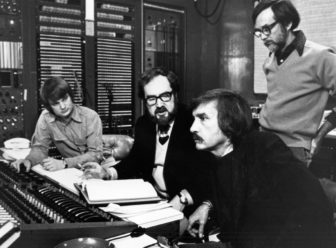

Schmidt, far right, with Tom Voegeli, John Tydeman and Edward Albee, working on Earplay.

Decades ago, Karl Schmidt occupied himself by staging elaborate award-winning works of theater for radio broadcast. At 90, he’s still weaving compelling stories on the air, but he’s down to a troupe of just one actor — himself.

With a voice that remains sonorous and agile, Schmidt hosts Chapter a Day, a show that airs weekdays on Wisconsin Public Radio’s statewide network. He’s been behind the microphone since 1941, likely making him the longest-serving host of any public radio show in the country.

Wisconsin Public Radio/UW-Madison Archives

Tom Voegeli, John Tydeman of the BBC, Edward Albee and Karl Schmidt work on an Earplay production of Albee’s play “Listening” ca. 1975–76.

Along the way, he held a variety of other jobs at WPR, and for most of the ’70s produced Earplay, a radio-drama series for national broadcast widely distributed by NPR. During his long tenure, Schmidt’s attention to his craft influenced younger hosts and producers who worked under his tutelage. And as host of Chapter a Day, his skill at bringing stories to life continues to inspire his colleagues.

“With the books he records today, he sounds just as awesome as he ever did,” says Mike Crane, WPR’s director of radio. Crane joined WPR in 2008 but had learned of Schmidt years before when living in New York. There he heard the dramatist’s radio rendition of the classic sci-fi novel A Canticle for Leibowitz, which aired on public radio in the early ’80s.

Schmidt found his way into radio through acting and stayed devoted to radio drama decades after its heyday of prominence on commercial airwaves. “A wag once said to me, ‘I know the best time to air radio drama — 1930,’” Schmidt says, chuckling.

But when the creation of NPR and CPB — which Schmidt had a hand in —made funding available for a national series, Schmidt and his Wisconsin colleagues seized the opportunity.

In the days of Earplay, the team at WHA, the flagship station of what is now Wisconsin Public Radio, was a “hugely creative group of guys,” says Tom Voegeli, a producer of public radio’s From the Top and creator of The Splendid Table. Voegeli’s father, Don, worked with Schmidt as music director of WHA. That connection gave Voegeli a way into radio and an introduction to Schmidt, who became the young producer’s first mentor.

“It was wonderful to work with him,” says Voegeli, who worked as a mixer and audio technician for Earplay. “It gave me an amazing toolkit that I’ve always used as I’ve done all the other production in my life.”

A home in Wisconsin

Karl Schmidt began finding his way toward his long radio career as a youngster growing up in Canton, Ohio, where he started acting in regional theater productions. When his voice changed, he sounded older than his youthful appearance, making radio theater an even better match for his talents than the stage. Soon he was working for the Mutual Broadcasting System, which was producing shows at a station near Canton.

Seeking a long-term career in the field, he went to the only school at the time where a student could prepare for such a job: the University of Wisconsin in Madison, home to one of the country’s oldest radio stations, WHA-AM. Schmidt enrolled in 1941, then went off to serve in World War II, working for Armed Forces Radio in the Pacific for three years.

He earned a degree upon returning home, then went to New York to try to break into radio theater. “There were too damn many actors and too few usages of them, and it was getting worse and worse,” he says. “The radio drama that was done there was all pretty soapy — I didn’t care to spend my life doing that.”

And Madison had become home to him. With programming such as its Wisconsin School of the Air, a series of programs used for teaching children in rural one-room schoolhouses, WHA lured Schmidt back to Wisconsin.

“My parents didn’t get beyond eighth grade in school — they had to leave to support their families,” he says. “I thought that if my parents had had the cultural opportunities of living in Wisconsin instead of a small steel town in Ohio, their lives would have been broadened immensely. And that appealed to me.”

After returning to Madison and WHA, Schmidt stayed for good. He worked in production and as chief operator, then as director of radio. He also served as director of the National Center for Audio Experimentation, which experimented with techniques such as compressing speech to speed it up, and creating effects in panoramic sound.

Later, Schmidt was a founding board member of NPR and an associate chair of the National Association of Educational Broadcasters. When the passage of the Public Broadcasting Act led to increased funding for public broadcasting, Schmidt jumped at the chance to return to radio theater — and this time, he didn’t have to leave Wisconsin to do it.

With support from CPB and the National Endowment for the Arts, Schmidt launched Earplay in 1971. The series featured original plays written by talents including Edward Albee and David Mamet. Distributed by NPR, it was carried by 100 stations — about 90 percent of the system at the time, according to Schmidt.

The show benefited from an exchange program that Schmidt orchestrated with the BBC, renowned for the quality of its radio dramas. Staffers from the BBC’s radio drama division took leaves of absence to visit the U.S. and work on Earplay. One such visitor was script editor John Madden, who later went on to direct the films Shakespeare in Love and, more recently, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel.

Earplay won a Peabody Award and a Prix Italia, the highest international honor for radio drama. But it failed to find much of an audience, and the fortunes of radio drama have only continued to diminish.

“I still wish I could do radio drama,” says Voegeli of From the Top. “But there’s absolutely no market for it.”

Yet the producer says his time working for Schmidt imparted lessons about radio that he still uses today: the difference between projection and volume in using one’s voice; how to make transitions and coach talent; staying in a scene even when not speaking; and making a script sound natural.

Voegeli has kept in touch with Schmidt, who played a role in the first radio drama that Voegeli wrote, when he was a high school student. When Voegeli’s father passed away, Schmidt delivered a eulogy that “was one of the greatest pieces of performance I’ve ever seen,” Voegeli says. “It was so touching, so funny.”

Lunch-hour readings

After Earplay went off the air, Schmidt retired. But he’s continued to host Chapter a Day, which started on WHA in 1927 when a guest canceled and the host read a library book aloud to fill time. It now airs on WPR’s Ideas Network at 12:30 p.m. and 11 p.m. weekdays. On WHA, it often draws as many listeners as the station’s locally produced morning talk show, and sometimes more.

“A lot of people seem to organize their workday around Chapter a Day,” says Jim Fleming, who worked with Schmidt on Earplay and now hosts To the Best of Our Knowledge. He also reads occasionally on Chapter a Day. “People make sure they have lunch, a radio and a room to themselves so they can listen to the broadcast every day.”

Schmidt picks from classic and contemporary works of fiction, excerpting and editing to fit the work into half-hour chunks. Sometimes he ventures into biographies as well. When appropriate, he affects accents to bring different characters to life.

“Reading for radio is a real skill — it’s not as simple as people think,” says Fleming, who calls Schmidt the best reader he’s ever heard. “He understands how to bring life to the printed page.”

Each novel usually gets two to five weeks on Chapter a Day, but that can vary. Recently, Schmidt was working to adapt Back to Blood, the latest novel by Tom Wolfe, to the program. The famously verbose writer’s leisurely approach to narrative posed difficulties — “Three hundred and fifty pages in, and it’s still exposition,” Schmidt says. “He’s still adding characters!”

So Schmidt considered incorporating a review of the book into the program and giving Wolfe only a week. “It’s a cop-out, but it’s the best I can do,” he says. The best novels for the show are contemporary and have relatively few characters and straightforward plots, Schmidt adds.

The listener response to Chapter a Day gratifies Schmidt, who especially relishes letters from truck drivers who stumble across the show and listeners younger than the “teacup brigade,” as Schmidt calls his older cohort. His own children weren’t interested until two of them got jobs painting houses. “That put them in a situation where to be read a story is attractive,” he says. (One of Schmidt’s sons, Dan, is now president of Chicago’s WTTW.)

Now in its ninth decade, Chapter a Day could just keep on going. “It seems pretty easy to imagine that Chapter a Day will continue to be on, because the response is so positive to it,” says WPR’s Crane.

And it’s likely that Wisconsin’s radio listeners will continue to be read to by Schmidt, a host only a bit older than his signature program and one whose legacy extends beyond his home state. “I certainly am thankful that things worked out this way,” Schmidt says. “I’ve had a good time here, and I feel that I’ve made a contribution.”

His colleagues would confirm that hunch.

“Without him and people like him, we wouldn’t have this extraordinary service we have all over the country,” Fleming says.