Luis Perez may not be a typical public radio host, but he’s typical for Chicago Public Radio’s Vocalo.org—young, a newcomer to radio, and reflective of the diversity the station wants in its audience. (Photo: Mike Janssen, Current.)

Vocalo’s test ahead: Will it be in with the out crowd?

First of two articles

The afternoon team at Chicago’s newest noncommercial radio station is on the air, talking crime and punishment. Most public radio shows would steer a conversation about the city police force along a course charted by producers well in advance and predictably typecast with expert pontificators. Not Vocalo.org.

Host-producer Robin Amer shares news of a personnel change in the Chicago police, a nugget fresh from the website of the Chicago Sun-Times. Co-hosts Dan Weissman and Luis Perez grill her for details from the just-published bulletins in front of her. So far, no one here knows many facts to add to the breaking news, but the loose discussion opens a window for soliciting other perspectives on policing. Weissman brings in context from cop-related blogs that he calls up on his laptop.

Their freewheeling conversation flows into audio clips of Chicago residents discussing cops and what they do, often over a rhythmic beatbox loop or between snippets of music.

Perez dips into the station’s ENCO database of thousands of listener-contributed segments, searchable by subject. First comes a piece uploaded in May by a Vocalo.org user, screen name Greg, about police cameras in his neighborhood. “When they first put the police cameras up, I felt as if I was going to be safe walking around the neighborhood, but it’s still the same,” he says, with no crime stats to recite or politicians to quote.

In the next clip, an unidentified resident of Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood argues that to be effective, a cop has to come off as tough. Then a slice of a hip-hop track: the Merchant Boyz’ “What the Hood Made Me.”

The unpolished remarks, with their heavy doses of music, don’t seem to come from a soundproofed room. No single topic gets the intense scrutiny typical of an hourlong installment of The Diane Rehm Show, for example. But Vocalo.org’s broadcasts often approximate the effect of overhearing intriguing conversations at a neighborhood coffee house, one where the kibitzers know local politics as well as pop culture.

The overall vibe is far different from that of WBEZ, Vocalo.org’s sister station at Chicago Public Radio, or of most other public radio news outlets. That’s no accident — Vocalo.org is CPR’s bid for a younger, ethnically diverse audience turned off by public radio’s more buttoned-up tone.

A signal upgrade on the station’s transmitter in northwest Indiana, expected to win FCC approval any day now, will give Vocalo.org significant reach into the city of Chicago for the first time since signing on last summer. After 18 months of experimentation, Vocalo.org’s creators soon will have a substantial mass of listeners who can judge whether their creative instincts have hit their mark.

“I think we’ve got a good shot at this,” says Torey Malatia, Chicago Public Radio’s president and a passionate evangelist for Vocalo.org’s mission. “It’s not a pipe dream, even though it seemed like it a year ago.”

Cozying up to nonlisteners

Malatia and his staff began planning Vocalo.org in 2003 as they contemplated a new format for 89.5 FM WBEW, Chicago Public Radio’s repeater in Chesterton, Ind. At first they floated the idea of an all-music format, but Malatia came to doubt that music programming could compete in a media landscape burgeoning with web streams, satellite radio and iPods.

Meanwhile, WBEZ’s audience trends troubled him. The audience of the all-news NPR affiliate, though healthy in size, had stopped growing. It was also 91 percent white in a city that’s only 60 percent white, with rapidly growing contingents of ethnic newcomers.

Through surveys and focus groups, CPR studied Chicagoans who didn’t listen to WBEZ. It encountered sobering criticism, especially from blacks, Latinos and Asian-Americans who participated. They said the station’s clubby, “in-crowd” sound failed to appeal to them. And their appetite for local content, greater than that of WBEZ’s core listeners, was not satisfied by the station, which like most NPR affiliates airs mostly acquired programming.

“For a broadcast service, operating in the name of the public and available free to anyone in the city who has a radio, it was humbling to see that service was judged useless by so many in Chicago’s big nonwhite population,” Malatia wrote in a paper about the birth of Vocalo.org. (Read it at Current.org: tinyurl.com/6qmpvl.)

Malatia’s staff hatched Vocalo.org as an answer. The station aims to attract those disillusioned with public radio through its mix of music, talk and user-generated content. That’s the staple called UGC, an acronym staffers frequently refer to in casual conversation.

Vocalo.org disguises itself to seduce skeptics. Its hosts and promos never call it “public radio.” The station never holds telltale pledge drives. The on-air staff is young and diverse, reflecting the audience they hope to attract. Most are under 40 and lack radio experience—Amer, an alumna of a similar experiment in public radio, Christopher Lydon’s defunct Open Source, is an exception. They came from backgrounds in art, theater, music, stand-up comedy and other nonelectronic pursuits.

Vocalo.org also fuses elements from the Web 2.0 playbook that pubcasters elsewhere are tinkering with. Its extensive website (vocalo.org) serves as a conduit and filter for the UGC that reaches the air. These community-based users and others create profiles on Vocalo.org a là Facebook or MySpace, where they can write their own blogs, upload audio and video, and comment on or create playlists of other users’ contributions. Malatia expects that in time, the site will also serve as the bedrock of the station’s sponsorship income.

“In order to make this work, the key is to begin to develop a real interest in the website,” Malatia says over lunch at a restaurant near CPR’s Navy Pier offices. “Our feeling is that to market this as a radio station in a traditional way — ‘There’s a brand-new radio station on the air!’ — is not only the wrong way to go, it’s also completely unnecessary.” A successful Vocalo.org will send listeners from the broadcast to the website and vice versa, much as Open Source aimed to do.

To cultivate UGC from the audience it aims to attract, Vocalo.org’s host-producers go out into targeted communities to recruit contributors. Some borrow equipment and keep radio diaries, interviewing friends, family and neighbors. CPR has also organized monthly workshops throughout the city covering audio production and usage of the Vocalo.org website. More than 100 trainees have attended over the past year.

By reaching into the community, Vocalo.org aspires to a much higher proportion of locally rooted coverage than WBEZ offers. Yet the new service shares a goal in common with many mainstream public radio stations: connecting individual listeners to a broader community that surrounds and defines them.

For the past year, CPR has shied from promoting Vocalo.org all that much, and its signal barely reaches the city. The young station’s audience reflects that. It hasn’t even cracked into Arbitron ratings, and its web stream gets just 100 to 200 unique visits each week. Vocalo.org’s website has about 3,300 registered users, but one in three has contributed content.

Vocalo’s creators expect that to change when the FCC okays the signal upgrade. The signal previously reached Chicago only when weather cooperated, and then mostly along the Lake Michigan shoreline. Its total coverage: 350,000 potential listeners, mainly in northwest Indiana.

The expanded signal is expected to reach upwards of 2.5 million potential listeners in Chicago’s south side, downtown and perhaps even farther north.

So experimental, your mom can’t keep up

Back in the studio for the afternoon, Perez is behind the control board. He sometimes pauses a UGC segment so he and his co-hosts can interject comments — along the lines of a skeptical “What’d they just say?”, for example. Then he resumes the segment. Few board ops at other stations would ever attempt this — imagine a local host dropping out of Talk of the Nation mid-segment to challenge Neal Conan. The novelty is ear-grabbing.

“Interrupting a piece feels honest,” says Amer. It feels fresh.

With the end of his team’s shift, at 4 p.m., Perez surrenders the board to Navraaz Basati, a host-producer who also moonlights as the lead singer for Funkadesi, a world-music fusion band. On air, she creates yet another sound, playing brief clips of UGC grouped by theme. The cuts come and go in rapid succession, like on an iPod on shuffle.

Basati drops in to forward- and back-announce the clips with breaks just seconds in length. Later, she’ll listen back to the shift to evaluate how well the segment came off. The experiment will help determine how much UGC Vocalo.org can program and whether hosts can get by solo or in smaller teams.

The stop-and-go UGC and other trademarks of Vocalo.org’s on-air sound stemmed from months of relentless experimentation since Content Director Lloyd King arrived in June 2007. “When I first got here, it didn’t sound good,” King says. “It sounded like bad college radio.” (He still hears this complaint from some listeners.)

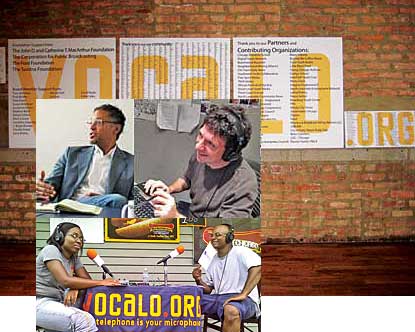

King (top left), Vocalo.org’s content director, spurs his staff to experiment and champion their successes as models for the station’s future. Host Weissman (top right) and teammates recruit Chicago residents to contribute online and on-air by staging remote broadcasts. Shantell Hamison (lower photo) interviews Chris Jones during a remote from his barbeque restaurant. (Photos: King and Weissman by Mike Janssen, Current; Jamison by Dan Weissman, Vocalo.org.)

A podcaster, musician and former music teacher, King began trying out different combinations of hosts and varying the proportions of UGC and other content. The fluctuating schedule and demands proved difficult for some host-producers to keep up with.

“We had a schedule that was all but random to an untrained eye,” says Weissman, a longtime journalist who has also taught in community arts programs in Chicago. “My mom could not keep track of when I was on the air.”

Today the schedule has solidified into 12 hours of original content each weekday and three hours on Saturday. The rest of the time is filled with repeats of archived air shifts. Each broadcast team — known as Teams W, X, Y and Z — includes three hosts. The morning team’s humorous tone sounds somewhat like commercial drive-time radio, King says. The two midday teams fuse the journalistic DNA of NPR’s Bryant Park Project with a dose of UGC. And the evening team is “trippier and artier,” he says — a throwback to Vocalo.org’s extremes of randomness.

The division of labor and on-air shifts are now more settled than ever. But January 2009 will bring another shift, as Vocalo.org aims to use even more UGC and get more hours of original content from the same team of host-producers.

“Everyone should be making strong arguments about what Vocalo is and how Vocalo should be run,” King says. “Whoever makes the best arguments wins.”

King’s host-producers are skeptical about eking out more broadcast hours, which he answers with optimism. They do appear to have their hands full, however. After their air shift, Amer, Perez and Weissman gather outside Weissman’s cubicle to brainstorm future programming.

Perez idly tosses around a Wiffle ball as they talk. They agree that recent outreach to the North Lawndale neighborhood, a largely black area on Chicago’s west side, has given them fruitful contacts for UGC and community reporting. They staged remote broadcasts from a barber shop and a barbecue joint, for instance. But it’s a struggle to balance that outreach with their on-air and online responsibilities.

Even with these pressures and Vocalo.org’s sound still a work in progress, the hosts look forward to their true on-air debut, nearly a year and a half after the experiment began.

“We’re as ready as we’re going to be to play to a larger audience,” Weissman says. “And we won’t know more until the audience hears it.”

Continued in On South Side: Awaiting judgment, Vocalo gets practice.

Web page posted Dec. 8, 2008

Copyright 2008 by Current LLC