Kling at PRPD: ‘Why haven’t we grown more?’

‘I am not satisfied. I haven’t done enough, and neither have you’

The closing speeches of Public Radio Program Directors Conferences, styled as “benedictions,” more typically send attendees to the airport with misty, satisfying reminders that they’ve got some brilliant stars on the air. For this year’s, Sept. 29 [2007] in Minneapolis, PRPD brought in the Minnesota Public Radio chieftain from St. Paul, who had just added a Miami station to the American Public Media Group. Kling bade the audience to go forth and get busy.

According to the dictionary, the word “benediction” means “a short invocation for divine help and guidance.” This may not be short, but it certainly prescribes a vision that needs both divine help and guidance.

I often use the word success in describing public radio, yet what I really want to say is that while we should all be proud, we have barely touched the potential of our kind of media.

Today, in Minnesota we have 850,000 regional listeners, or about 17 percent of the population, who receive programming over MPR’s 37-station network.

Across the country, American Public Media produces and distributes programming heard by 15 million listeners each week. NPR has something over 23 million. All of public radio — in all formats — reaches something like 30 million. In Seattle, KUOW is the No. 1 station. In Los Angeles [see sidebar], KPCC is the No. 1 news station. And there are more success stories.

Those statistics show real progress since the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, and yet I still find myself asking:

- Why haven’t we grown more?

- What will convince new talent to work in public media?

- Where is the strong leadership this system deserves?

- With all of the new media options and the changing media landscape, does what we do every day make a significant difference?

I think the most important rationale for public radio is our growing role in helping maintain an engaged citizenry and a “democratic society.”

My greatest concern is that the American public is increasingly disengaged from civic issues. Madeleine Albright recently put it this way at a conference I was attending: There are two ways to lose your democracy—by having it taken away or by neglecting it. And information is the key to maintaining it.

Today in Russia and Venezuela, it’s being taken away. In America, we are neglecting it. And that’s why public radio and public media are so important.

The impact of media changes of the last 25 years, from cable television to the Web, has taken away the ability of the old “mainstream media” to serve their critical role of focusing the public discourse. CBS once could do that with a major documentary in the 1960s. Not now. And neither can anyone else. The New York Times reaches 1.7 million people with its Sunday edition. Public radio reaches 30 million. But the country has 300 million.

Just last month, a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center showed that more than half of Americans — that’s more than 150 million people — think U.S. news organizations are politically biased, inaccurate and don’t care about the people they report on. That means that half the population is either tuning out or not engaging with current news programming.

As the criticism of news coverage by commercial media grows, one of the results is that informed discourse in American public life has dropped to an alarmingly low level. We hear this loudly from teachers, who find students increasingly clueless about any kind of civic issues. This growing civic illiteracy makes public media more important than ever. Our role in providing responsible, relevant, public interest-oriented content has never been more important.

We need to be creative in how we build our audiences as well as our content. Maybe while you’ve been here you’ve heard the Current [89.3 FM] — our effort to reach younger audiences. I was delighted to see that 60 percent of the Current listeners now choose MPR news as their second-choice station. That was our objective.

Just yesterday, I got an e-mail from a listener to the Current who said: “I got into ‘talk’ from the Current. Now I’m addicted. I’m 24.”

I think our listeners would tell us that public radio is an important part of their lives, helps them be better citizens and that it has a positive impact on their communities.

They listen to MPR stations a lot — an average of seven to eight hours a week. They come to events, and they seek us out online.

Surveys indicate they also trust us. We have a content niche — an increasingly important one. And we have the audience of opinion leaders we sought — just not a large enough one.

Our ability to be seen as trusted sources of relevant, local programming — as true community institutions — will make the greatest difference in the future.

Public radio stations, like most traditional media, are at a critical juncture. We need to be smarter about accomplishing our mission and we need to have a clear vision — now. We need to anticipate what our audiences want and where they will turn to get it. We have to become institutions of consequence in our cities. And we need to be “players” in those cities.

We now have an industry with the unusual combination of mission, values, technology, show business, growth, opportunity, potential and more. I’d argue that this is the most exciting time of my career to work in public media. Our financial compensation as an industry has improved in many cases, and we should be attracting strong applicants for our open jobs.

While we are moving ahead on all platforms, so are newspapers and TV networks and cable networks. Yesterday, you heard Robert Stephens [founder of the Geek Squad computer repair business] emphasize the importance of social networking in creating a community like ours.

Most stations haven’t done much about that, and we are letting the likes of Facebook.com run away with our potential audience. APMG has made a significant gamble in creating a place for the public radio demographic to participate in social networking by creating Gather.com. Millions of dollars have been invested in the technology and tools. Our hosts love it. They extend their shows on Gather. They partner with Gather. They draw ideas from the Gather audience. It’s another tool for us and for our audience that we couldn’t otherwise afford, that builds connections between our audiences and loyalty to us, and that any one of you can use free.

In various sessions here we’ve shown you a couple of APM/MPR’s new online games. One is our Consumer Consequences game. It deals with the important issue of sustainability. It has been up for 30 days and has had 41,000 people use it. That’s 41,000 people newly aware of their personal impact on the sustainability of the earth.

We ran another game during the elections: Select a Candidate, which matched the political priorities of individual Minnesotans with the candidate most closely aligned with those interests. It had 107,000 users in the months running up to the last elections.

The point of both is to find ways to engage the public that are interesting to them—while at the same time, telling us more about how they think. It may be the kind of thing we need to do to get the attention of a society that is more likely to be able to tell you the finalists on American Idol than the names of the Republican candidates for president.

That doesn’t mean we should throw out the fundamentals that we’ve depended on to build our radio stations. Radio is the mother ship, and its strength will drive the success of all other platforms.

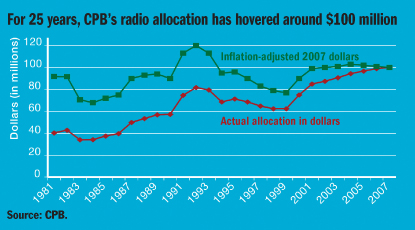

What we don’t do, the reason is mostly that we can’t afford it. Yet for years our federal support for public broadcasting has hovered around the $400 million level. In inflation-adjusted dollars, the public-radio budget at CPB hasn’t changed in 25 years and still hovers around the $100 million level (graph below).

Could it change? Public radio has many assets, and one of them is our audience. Are we effectively using that audience and its influence? Could we find ways to engage them to use their influence and move our appropriation closer to $1 billion? Or more? If a political campaign had our assets, you can be certain, it would have used grassroots political tactics to get much greater impact and results than we have.

Why not a billon—or more? The Congress spends that much on many other programs with less impact and on programs with backers who have far less influence than our audience does.

We haven’t engaged the leadership that we know is there in our audiences. We haven’t drawn our audiences together with us beyond listening. But we could. And that would make the difference. As anyone at APM will tell you, after playing a role in almost every aspect of the development of this wonderful medium of public radio, I am not satisfied. I haven’t done enough, and neither have you.

Here’s what I think we need to thrive: Leadership, Vision, Money. Those are the three elements where I think we have to perform better. If we do the first two well, the third will come.

Leadership

Effective leadership for our stations requires both an engaged board of directors (or board of supporters of some sort) and a talented, committed, capable management team.

Enlisting a strong, interested, influential board of outside trustees was the first step we took in forming Minnesota Public Radio and American Public Radio and APRS and Southern California Public Radio and PRI and APM, etc. At MPR, we are careful to recruit people who are leaders in the community — people we thought would be ambitious on behalf of Minnesota Public Radio and demanding of me and our leadership team.

Over its history, our industry has had some strong leaders. But, I wonder if our expectations for those who hold the top positions on our boards have been too modest. While our leadership has some great success stories, I wonder if we or our governing boards really search to find the most capable, experienced candidates. And when we have them, have we done what we need to do to bring them together to use their joint networks to advance our system?

In hiring, do we recruit? Do we find the strongest leaders for our stations and our national organizations? Or do we tend to hire too often and too easily from each other? Or promote employees into top posts because they’re a known quantity—when they may not be the best qualified?

We need to become much more demanding and deliberate in choosing our top leaders. That’s where the difference will begin.

In an industry report card: I think we’d have, at best, a “C” in leadership. You can argue with me that we’ve done OK. But compared to our potential, and now to our growing mandate — we should be way above average — and, by and large, we aren’t. With our potential and our assets, we should be blown away by the achievements of our leaders — and generally we aren’t.

We have not had the leadership, and the structures or organizations to accommodate that leadership, that would have resulted in a billion-dollar federal appropriation — or in identifying very many managers who could build stations with, say, an average budget of $25 million or more.

But we could do it.

Vision

Vision is the second of the three fundamentals. What could public radio become in this country? Is setting the BBC’s role and achievements in England too high a hurdle?

With the economics of most other domestic information providers arguing against their providing quality content — quality news, quality arts programming — how high should we set our sights? Why are we so timid about our potential?

Vision is what we need — to see the best options for us in the future. An ability to communicate that vision is vital if we’re going to win the support that we need to make that vision a reality. That means taking the time to bring together a capable group of strategists and idea people to communicate our vision. The Public Awareness Initiative is one good start at that! But other initiatives, driven by strong external leadership, will also be necessary.

Here are a few questions I try to answer in thinking about our future:

- What makes us, as local producing stations (not network repeaters), relevant?

- What are our changing obligations, as a result of the weakening of other media?

- What is the plan for attracting new audiences?

- What is the best technology to reach those audiences?

- Do we have the quality and experienced people we need?

- How do we promote and reward risk-taking and creativity within our stations?

- What is our plan for audience engagement, beyond broadcasting, to bring the audience together in other parts of their lives beyond just being listeners? How do we connect with listeners?

- How do we create the place that builds value and loyalty and that our listeners will trust?

- How do we find the money to become the kind of organization we see as our future?

Each of these is a multifaceted question, and the answers will result in different strategies for different kinds of stations. Some of you are in a position to take major steps forward, and others might be in riskier positions where it’s best to try for gradual change. Trying is what matters.

Developing the vision, though, is only the first step. Getting others to buy into it is just as important. Effectively communicating your vision and selling it, energizes employees and generates revenue from donors to implement it. Great ideas may fade without the help of people who know how to make them come alive.

Our experience has taught us to paint a clear picture of the vision, of what could be, if the vision were realized. And then being aggressive about telling the story to anyone who can help. The APM/MPR studio facility that many of you saw the other night is a great example of what can result if you communicate effectively with those who already value you.

Localism

I want to talk about the vision for localism for a minute. “Localism” is a fundamental element that has helped us become a significant community player in our region. Today it’s also what every regional newspaper is touting aggressively.

Certainly national programming is important, and it contributes to our stations’ significance. But local programming is equally important. It completes the definition of what public radio is and should be. And it’s increasingly what differentiates our stations from others. Local programming may be our most compelling strategy in a technology-driven future where localism and the technology are less compatible.

I don’t think you can become a “significant community institution” solely by transmitting national programming.

Local quality

Every day at Minnesota Public Radio, we face a question that haunts us about our programming: What if we’re not good enough? What if the programming we are producing, or that NPR is producing, or that American Public Media is producing, isn’t equal to the mission we’ve been handed?

One solution we’ve found is to engage the public by tapping their knowledge and expertise in helping us develop our news and information content. We do it through Public Insight Journalism. If you went to the session here, you know that the Public Insight Network now has more than 30,000 members, and it’s become an essential tool, embraced by our reporters. They openly state that they simply could not get stories as good or as thorough and accurate without it. And that’s an affordable solution for nearly any station. It has the potential to raise the quality of your programming and with it your relevance.

Brand

A part of vision is an identification of who we are. Your audience knows you as NPR, as Marketplace, as PRI, as KXYZ, as Wisconsin Public Radio, as American Public Media. In most instances — our company included — we have not clarified the message we want the audience to get. Every station break is a hodgepodge of brands.

If you’ve been listening this week, you may have noticed that in Minnesota, “Minnesota Public Radio” is the brand, and NPR, PRI and APM are given credit as services provided by Minnesota Public Radio. In Minnesota, Minnesota Public Radio brings you Morning Edition or Marketplace.

If you want your audience to support you — both financially and with their personal influence and networks — you need to balance the branding credit so that they realize you exist.

If you think NPR is more important than you are in your community, and if you ride on that brand — “NPR for all of Minnesota” for example — then that’s the brand you are telling your audience is the most important. And that’s where their loyalty — and their money — will be. On the other hand, “This is Morning Edition, I’m Cathy Wurzer in St. Paul with Steve Inskeep in Washington . . . ,” which you may have heard here this week, supports the station brand. And as our network, American Public Media, knows well, when stations do well, networks automatically do well.

My formula

Leadership, vision, localism and branding, and money comprise the foundation for building stations into “community institutions.”

Here’s the irony. The more successful we become as “significant institutions,” the more we need to act and think like entrepreneurs, because more will be expected of us. And that raises our costs at the same time competitors are increasingly targeting us.

But I can see no justification for not making the changes that are so clearly needed to reach our full potential — while we still have the opportunity.

Making it happen

We can’t hide anymore. Our mission is too important. Our licenses are too important. The opportunities are too great. Our achievements thus far, while significant, are closer to the beginning — than the ideal. And all the while, we are in the envious position of having our traditional competitors fading away.

If we identify the leadership, engage the influence of our audience and explain our vision, I see no reason why we can’t reach unprecedented heights for quality local and national programming, funded by unprecedented levels of local and CPB funding.

There is urgency to this message. We have a window in time when the wind is behind our sails. We need to take advantage of that before someone sees the weakness in our vessels and invents a better boat.

Thank you for being willing to listen to me talk about my passion for public radio.

Web page posted March 10, 2008

Copyright 2007 by Current Publishing Committee