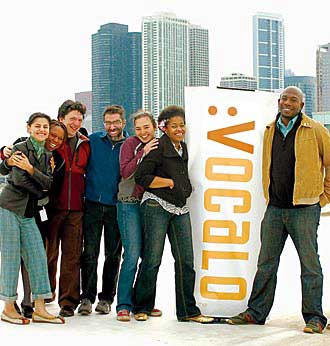

Only one of the first seven hires for the iconoclastic station has previously worked in radio. (Photo: Chicago Public Radio.)

The new station signing on in Chicago next month departs so dramatically from convention, listeners might never guess it’s public radio—which is exactly the point.

Chicago Public Radio’s :Vocalo attempts an ambitious fusion of talk radio with an extensive website where users can network and share their own writings, recordings and videos, some of which will be curated for broadcast by an eclectic team of host-producers.

CPR execs hope this cross-pollination between web and broadcast and within a diverse audience will create a unique, listener-driven sound that draws in Chicagoans disenchanted by the usual pubradio fare on CPR’s existing news-talk service, WBEZ.

“This is probably the most transformative and comprehensive experiment with a signal and a new website that I can think of,” says Torey Malatia, CPR’s president. “It just throws a bunch of stuff out the window.” (Malatia explains the thinking behind :Vocalo in a Current Thinking essay in this issue.)

:Vocalo’s hosts will never say “public radio” or “pledge drive.” Nor will they promote individual programs—there won’t be any. They’ll hold down shifts like their counterparts on commercial stations, but rather than cueing up singles, they’ll anchor a continuous stream of features, interviews, commentaries and other material, most ranging from five to seven minutes’ length. The station will carry no programs from national distributors, not even NPR newscasts.

If all goes according to plan, much of this content, heavily focused on people telling their personal stories, will come from the station’s companion website.

:Vocalo, whose name blends “vocal” with “zocalo,” a word in Mexico for a town’s plaza, launches online this week with limited pilot material, at vocalo.org, and hits the airwaves June 4 on WBEW, CPR’s 7,000-watt FM station in Chesterton, Ind. An upgrade to 50,000 watts, expected by the fall, will expand the station’s reach to 4 million people in northwestern Indiana and southern and central Chicago.

CPR’s initial plans for the Chesterton signal reflected a far more typical pubradio strategy. In December 2004, Malatia told his staff that WBEW would become an all-music station, freeing ’BEZ to focus on news.

But in April 2006, CPR hinted of its new plans to Chicago media, angering music fans. The growing popularity of satellite radio and iPods caused Malatia to doubt the competitive advantages of an all-music service, he says.

Meanwhile, he began to feel that CPR was becoming dangerously estranged from its changing city. Even as Chicago became more racially diverse—41 percent of its service area’s population is nonwhite—WBEZ was reaching an audience that was 91 percent white and not growing.

The station began an extensive study of Chicagoans who didn’t listen to WBEZ. Many who shared opinions in surveys and focus groups said they felt “unwelcome as listeners” and thought little of public broadcasting in general, according to Malatia.

“This is the first time I’ve ever confronted the reality that maybe PBS, NPR and PRI are like dirty words” to some people, Malatia says. “You don’t think about that.”

Yet the respondents did have an appetite for news and for a radio station that lived up to public radio’s mission. Many non-listeners, particularly those in ethnic minorities, scoffed at the name Chicago Public Radio because to their ears it aired hours of news from elsewhere and much less about Chicago.

CPR board members, staffers and managers began to rethink what they’d do with WBEZ as well as the new station. About a year ago, Malatia asked eight staffers to flesh out the ideas behind the new station. On Feb. 1, one of the eight, membership director Wendy Turner, became

:Vocalo’s g.m.

Vocalo will eventually employ 20 staffers, six behind the scenes and 14 host-producers who, in addition to holding down air shifts, will drop in on vocalo.org to spark discussions and mingling among users. Malatia envisions the host-producers as members of a theater troupe and facilitators for audience participation. “We want to raise the audience to the primary position,” he says.

CPR has hired seven host-producers, and only one has experience in radio. “They all would light up in a conversation that involved the community we live in, Chicago and the region,” Turner says, “and when they talk about discovering new things.”

Host-producer Bibiana Adames had recently started her own life-coaching business when she learned of :Vocalo’s search for hosts. Adames, a 32-year-old immigrant from Colombia with a career in mental health services, says the station’s community-building focus piqued her interest.

Because :Vocalo veers so sharply from public radio’s norms, CPR execs have no surefire way to know whether they will reach their desired audience of a younger, more racially diverse set of Chicagoans.

They acknowledge their effort is a gamble. CPR has budgeted $1.8 million for the project’s first year of operations but has yet to land a penny of the foundation funding expected to carry it through infancy. The station will also seek corporate sponsorships, both on air and online.

CPR is also working to develop new metrics for gauging

:Vocalo’s progress. Malatia points out that even a successful :Vocalo may suffer from limited listening time, as its short segments and frequent promotions of the companion website give listeners many opportunities to tune out.

Audience diversity will be a key index. Malatia hopes for an audience that will be at least 65 percent minority. “This should be a mixed audience. It shouldn’t be an audience for yet another specialized part of our community,” he says, referring to WBEZ’s appeal to the city’s affluent, white and well-educated listeners.

:Vocalo’s creators will also keep tabs on its profile within public radio, where some observers are already taking notice. Jake Shapiro, executive director of the Public Radio Exchange and an advisor to CPR on the project, calls it “one of the most exciting things underway” in public radio.

Most efforts to reach new audiences, to make websites central to new services or to solicit listener-created content “have been taking place at the margins, squeezed into existing formats and shows,” Shapiro says. “Vocalo starts with a clean slate and is forcing itself to write a new rule book for radio. . . . [I]t’s necessary and important and will teach everyone a lot as it unfolds.”

Web page posted March 15, 2007

Copyright 2007 by Current Publishing Committee