Onward with the TV arts

WNET follows City Arts with City Life — another show that’s cool, but not too cool

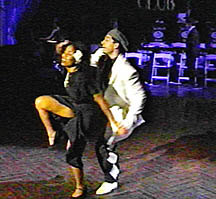

Indies make most City Arts segments, including Lisa Wood Shapiro's joyous visit to swing dance halls. |

It started as a series of love letters to New York's arts community, but WNET's City Arts has become an ongoing demonstration of what sharp young eyes can do with a handheld camcorder and many hours of editing.

The evocative, authentic, artful magazine-format series feels closer to an All Things Considered feature or a classic Life magazine photo story than to the serviceable routine of most nonfiction TV.

When City Arts won a Peabody Award in May, the jury called it "an exhilarating look at the creative arts in New York" and "a shining example of excellence in local television."

Since it debuted in 1995, the half-hour local program has won 14 Emmy Awards as well as the Peabody, and this spring spawned a daughter series at WNET. Though City Life also comes out of Jac Venza's arts unit, it ventures beyond the rehearsal halls and galleries, into the streets, shops and homes of the region.

City Arts also inspired handsome similar projects at WGBH (Greater Boston Arts) and WTTW (Artbeat Chicago).

You've seen work of the City Life crew if you watched the mini-doc profiles of nominees during WNET's Tony Awards coverage in June.

City Life inherits the City Arts personality,

based on unobtrusive small-format videography, the talents of some 120

independent producers who contribute during a year, and a no-narrator,

subjective style developed by former indie Jeff Folmsbee, who oversees

both series.

City Life inherits the City Arts personality,

based on unobtrusive small-format videography, the talents of some 120

independent producers who contribute during a year, and a no-narrator,

subjective style developed by former indie Jeff Folmsbee, who oversees

both series.

A similar program without these elements presents a jarring contrast: uninspired, shoulder-level shots from a standard, 40-pound camcorder, clop-clop-clop cutting, and a vastly thinner selection of quotes, moments and images collected in a single budgeted shooting day by a staff videographer.

City Life's first season let us watch a crackhead-on-the-rebound glimpse herself wearing lipstick for the first time in years; an immigrant pass his taxi-driving exam with a 96; a debutante practice waltzing with her Dad. It took us to a beauty parlor, where a customer lays out the entire story on an acquaintance: "She worked as a hairdresser for a while, and then she worked as a bellydancer on weekends. And she met a fisherman and they ran away together."

The scenes are caught because the shooter is working alone with a tiny camcorder--originally a semi-pro Hi-8 camera but now an equally small, $3,500 Sony DV camcorder--instead of a crew of four or five people. For some shots, the shooter braces the camera in a little Steadicam.

"When we started this unit up here I was deeply influenced by the kind of honesty and reality you can achieve in radio," says Folmsbee. "People seem much more human on radio than on TV." With just a microphone or a small camera, subjects quickly forget to act like they're on TV.

Though some WNET technicians have learned to handle the featherweight cameras, indies do most of the segments, bringing freshness, ideas and connections to many segments. Camera isn't only a technician's job. "They are writing the story by the way they operate that camera," says Folmsbee.

For a City Arts segment, Lisa Wood Shapiro spent many nights in dance halls to capture the joyous spirit and spectacular gymnastic dance maneuvers of 1990s retro-swing.

City Arts and City Life each has its own way of handling transitions. Arts ends each segment with time-and-place details for viewers who want to see things in the flesh. Life develops a theme, making transitions with on-screen text and regularly pausing to let us reflect briefly on city scenes in letterbox format--still lifes with movement.

The two series also share a look that comes from shooting in available light: the electronics crank up, creating video artifacts that look like grainy film, and the shutter slows down, making blurs seldom seen on TV. "We're not trying to look cool," says Folmsbee, a little defensively. "We're trying to get stuff that takes place in the dark." But it does look cool, and the producers often slow down their shutters even in daylight.

One transition delivers a mild zinger--revealing how little the debutante charity ball actually raises for charity. But the programs generally avoid the cooler-than-thou attitude of many youth-oriented media.

"Our job is to keep the point of view fair and honest," says Folmsbee. "Yes, we do have an editorial point of view. And that is: everybody has value. It doesn't matter whether you're a meatpacker or a prostitute or a debutante. That's what makes New York [expletive] great."

Climbs in and drives away Folmsbee was an independent producer learning Hi-8

several years ago when he made a piece for a WNYC-TV series about the

last man in New York who could repair the old Checker taxis, now extinct.

In one extended scene, a couple hires a Checker to waft them away from

their wedding. They climb in the cab, Folmsbee follows with camera running,

and the newlyweds drive away, staring at each other. The piece thrilled

Folmsbee and had the same effect on Glenn DuBose, now a PBS arts programmer

and then a deputy to WNET arts czar Jac Venza.

Folmsbee was an independent producer learning Hi-8

several years ago when he made a piece for a WNYC-TV series about the

last man in New York who could repair the old Checker taxis, now extinct.

In one extended scene, a couple hires a Checker to waft them away from

their wedding. They climb in the cab, Folmsbee follows with camera running,

and the newlyweds drive away, staring at each other. The piece thrilled

Folmsbee and had the same effect on Glenn DuBose, now a PBS arts programmer

and then a deputy to WNET arts czar Jac Venza.

"Then I knew I was talking to the right person," recalls DuBose. His half-hour meeting in a cafe with Folmsbee stretched to three hours, and he came away with a series outline on the back of an envelope.

With an initial $150,000 grant from the city, Venza pulled together funds for the first eight half-hours. Broadcast chief Ward Chamberlin gave the go-ahead. Cynical WNET old-timers who had seen many local series swiftly come and go, told DuBose, "Enjoy your year."

Five years later, City Arts does 18 episodes per season for about $1 million, largely from several major donors, mainly Dorothy & Lewis Cullman and the LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust. Other funders see the show and call to offer money.

For donors who care about the arts, "what better way to give those institutions exposure than through television," says Paula Kerger, WNET development chief.

The show celebrates all the arts, high to low, uptown to downtown, without skipping midtown. Small arts groups found City Arts boosted attendance noticeably, says DuBose, and galleries were particularly happy to get their first TV exposure. Even couch potatoes appreciate the series, he says. "I think it plays into a bit of the feeling that it's pretty great to live in New York City. Even if they don't go, they're happy to know about it."

After City Arts' first three years, Chamberlin asked Folmsbee to consider starting a second series. They considered and rejected doing profiles of famous people and places. They skipped over policy issues, which only "wonks" could love, Chamberlin says.

In May, City Life premiered for its four-episode pilot run, with Mark Mannucci as series producer. Daily News critic Eric Mink called it "a certifiable jewel." Chamberlin hopes to get funding to do eight episodes next year.

Chamberlin loves what Folmsbee, Mannucci and team do with the show. "They do television the way it can really be," he says--visual, memorable and telling about the New York region.

"When you see what other people are doing in New York, you can't help but relate it to your own life," says Chamberlin. "It makes you think about your own life and your children's lives." It makes Chamberlin want to learn how to use one of those little cameras.

"When I walk down the street, I notice I'm a little more observant of people. I attribute that to some of what my young friends have taught me."

Comments, questions, tips?

Page originally posted July 5, 1998

Copyright American University