Lightning in the sky: a call to confront death

Originally published in Current, Oct. 30, 2000

By Geneva Collins

Who'da thunk it: 18 million viewers tuned in last month to watch at least some of a six-hour series about death and dying. And they gave it a rating 58 percent above the PBS primetime average. Does this unexpected success of Bill Moyers' latest project, On Our Own Terms: Moyers on Dying, mean Americans are more ready to confront their own mortality than other media have given them credit for — or is the ratings feat just an example of how Moyers' Public Affairs Television and PBS have gotten really good at outreach and promotion?

Moyers himself acknowledges it's a bit of both.

"What this series has done is given people permission to talk about dying," he said in a recent phone interview. "On Our Own Terms says 'you're not alone.' When you discover that the person next to you on the bus is also thinking about the same experience, you suddenly feel you want to share."

People tend not to initiate conversations about death, said Moyers' wife and co-executive producer, Judith Davidson Moyers, in a training videoconference for station outreach personnel last spring. But when the producers put the subject of death on the table, people couldn't stop talking about it, she said. "Everybody has sort of a pent-up ... need to discuss the issues of death and dying."

What Moyers and colleagues learned several series ago is that it takes a lot more than a few broadcasts to put a topic on the table nationwide.

"TV alone is not enough," he says. "No matter how good a television program is, you have to spend a dollar on outreach for every dollar you spend on production." For On Our Own Terms, that translated to $2.6 million for production and $2.5 million for outreach.

The four 90-minute programs address the emotional, spiritual and financial turmoil of living with a terminal disease; explain the concepts of palliative care (pain management) and hospice work; explore the controversy surrounding physician-assisted suicide, and discuss health policy barriers to changing the system. Funding was provided by loyal Moyers underwriters such as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and Mutual of America Life Insurance Co.

Outreach efforts began a full two years before the series' air date, said Deborah Rubenstein, director of special projects for Public Affairs Television, Moyers' production company, which works with WNET, New York.

At Iowa PTV, Mary Bracken, programming and outreach coordinator, remembers climbing aboard in December 1999, when the state network hooked up with a pre-existing coalition: the Iowa Partnership for Quality and Care in Dying with Dignity: Advancing Comfort, Choice, and Control ("we call it the Long Name Organization," quipped Bracken). Outreach efforts often pose a challenge for statewide networks like Iowa PTV, she said, because "the project has to impact all 99 counties."

At least 73 Iowa towns and cities held events of some kind related to the series, she said, and the last two months before the September air date she worked on outreach fulltime, working with funeral home directors, libraries, churches and other organizations, using the series' elaborate leadership and discussion guides to spark project ideas. "We positioned ourselves as the conduit. . . . Our role was to put people with like project interests together," said Bracken.

Back in New York, Public Affairs Television enlisted the help of the WNET publicity staff and three outside media firms to get the word out — Vienna, Va.-based Barksdale Ballard & Co. worked with civic, community and consumer groups; Stewart Communications Ltd. in Chicago connected with health care associations and organizations, and Kelly & Salerno Communications of New York City handled publicity.

By April, more than 350 hospitals, universities, community organizations and local PBS stations were already in place to participate in a 90-minute training videoconference held by Bill and Judith Moyers and experts from the series. At the same time, the team launched a web site that provided leadership and discussion guides in a downloadable format, along with brochures, letterhead, graphics and program descriptions for stations and interested outsiders to copy and use.

"The most well-used section [of the web site] was the publicity tool section," said Rubenstein. "That was the lesson we learned from this project — the logos, draft press release, letterhead stationery with the boilerplate paragraph about the series — stations used that like crazy. . . . The Internet gives you a central distribution house, cheaply." Outreach was not limited by printing budget. Copies didn't sit unused in one state while running out in another.

Again, based on experience from previous Moyers projects, outreach included awarding 50 $2,000 "mini-grants" to stations to help cover the cost of mailing local resource guides.

Moyers spoke at the 60,000-strong AARP convention in Orlando in May and made stops at numerous other health- and aging-related meetings as well. It was after hearing Moyers speak at one such meeting that William Arnold, director of the gerontology program at Arizona State University in Tempe, got the idea to offer an online graduate-level course based on the series.

Twenty-two students took the course in September, most of them in the health care or social work professions, the gerontology professor said. His students' reaction to the series was generally positive, and he said he'd like to repeat the course in the spring, if he can find a way for students to have access to the series without having to fork over $99 for videocassettes.

KAET, the Arizona State University station that aired the program in Arnold's area, had prepared 1,000 information packets for mailing but got 10,000 requests. "Bill Moyers has done other specials that have been very popular," noted Arnold. "If Bill Arnold had been doing a show on death and dying it wouldn't have gotten this attention."

The Moyers publicity machine was responsible for getting articles in Time, Modern Maturity, Good Housekeeping, Money and other big-circulation magazines to address the subject the month the show aired. The Time cover story alone reached some 4 million households.

"We go after these media partnerships," said Moyers. "We say, 'We're doing this major show on death and dying. It's a deeper and more complex issue than we can cover, even in six hours. You ought to think about this and do your own independent inquiry.' ... We don't ask them to tout the series, but to take the subject of death and dying and cover it in their own style."

With media saturation coverage, the series' message points reach millions more pairs of eyes than ever watch the program itself, said Moyers. "We recognize there will be a cross-benefit of creating a larger buzz. We're not just trying to create a television program. We're trying to create lightning in the sky."

At PBS, the publicity and promotion folks did their part by giving On Our Own Terms the "Double U" treatment. Double U stands for unified and ubiquitous, said Judy Braune, v.p. for strategy and brand management. The promotion effort is an evolution of the so-called "pop-out" strategy introduced in 1996 by Braune's former boss, Carole Feld. Rather then promote a dozen specials lightly, PBS allocates its scarce financial resources to give four projects a year heavy-duty promotion to help them pop-out from commercial and cable competitors. On Our Own Terms was this year's first pick for star treatment; Ken Burns' Jazz will get similar attention before its January debut.

There are four components to the promotion campaign, said Braune. Paid ads, traditionally spent on tune-in publications like TV Guide a few days before air date, were purchased in publications like Good Housekeeping, Ladies Home Journal and Oprah's O, to target the series' presumed caregiver audience of aging female boomers. The second strategy was to use the web site more effectively and to engage in what Braune called "guerrilla tactics"—techniques like PBS and local station staff promoting the series in their e-mail signatures, so that every missive they sent out over the Internet contained a plug for the show. A third area was in station extension work, which included providing stations with a timeline that told them when and how they could promote the series. Fourth, PBS made sure its messages were aligned with media partners like Barnes & Noble, which had book displays on end-of-life issues in its 500-plus stores featuring a PBS-designed poster.

Some four dozen stations aired local programming to accompany the series, ranging from pledge programming-style phone banks staffed by trained counselors to documentaries of local terminal care centers. Some of the highest Nielsen ratings posted were in cities that had local programming, such as Seattle (KCTS' half-hour special explored the dying of a prominent Native American leader) and San Francisco (KQED's four 30-minute programs, collectively titled With Eyes Open and hosted by Ray Suarez, aired nationally as a companion piece to Moyers' series.)

In Kansas City, Mo., hospice workers staffing KCPT's phone lines during the broadcast logged more than 900 calls, said Nick Haines, executive producer for public affairs and news programming. "That's more than any other outreach project KCPT has ever participated in. . . . What's amazing to me, as someone involved in public affairs, more than the response, was the few numbers of complaints we received." Just three, to be precise.

The outreach campaign not only helps bring an audience together, but also lays the groundwork for post-broadcast evaluation. Foundations that cough up tens and hundreds of thousands of dollars for a project want to see how their money was spent. All of the hundreds of coalition partners that participated in promoting the show knew in advance they would be filling out forms logging the number of calls to their hotlines and requests for information packets.

Those numbers are still trickling in, said Rubenstein, and in the coming months the project team will assemble a thick report for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and other funders. A preliminary analysis of print coverage found that newspapers and magazines printed more than 2,000 newspaper and magazine articles about the series to date; the combined circulation totals nearly 300 million, said Rubenstein.

Nielsen numbers, web site mouse clicks, and calls for brochures can be easily documented, but how do you measure a program's effectiveness as a call to action?

It is a conundrum Moyers faces with every major series. He accumulates anecdotes by the thousands. His sports jacket pockets are routinely full of business cards and scribbled messages from people who have been touched by his programs — like the caterer carving the turkey in the buffet line who told him how his life was profoundly affected by the Joseph Campbell interviews back in the '80s.

"There are now 12 medical schools that offer a curriculum [on mind-body medicine] as a result of Healing & the Mind. The [University of California at] San Francisco Medical School had no course in end-of-life care, but they say they're going to start one because of this series.

"Over the next 20 years, who knows which medical students who watched these shows, how it will influence their behavior? I could never measure the impact," said Moyers. "It's why I have carried on a long, friendly war within public broadcasting about other ways of measuring impact than the quantitative ways of commercial television. We must measure our impact according to the imprint left on the people who watch."

‘Dr.

Kevorkian is

not heard from’

Physician-assisted suicide is one of the most controversial end-of-life issues,

and Bill Moyers covered it without the appearance of its most famous spokesperson

and lightning rod, Dr. Jack Kevorkian. In the third installment of On Our

Own Terms: Moyers on Dying, the journalist tells viewers, "In this program

Dr. Kevorkian is not heard from. We hear instead from patients, loved ones,

and doctors who talk about suffering and a death of one's own."

The program traces the different experiences of two terminally ill people.

One is an Oregon resident, Kitty Rayle, who completes all the paperwork to

have her oncologist administer the lethal drugs available to her through that

state's Death with Dignity Act. Although she ultimately dies without her physician's

assistance, she finds comfort in knowing she had the option. Jim Witcher,

a veterinarian in Louisiana suffering from Lou Gehrig's disease, wishes his

physician had the authority. Although Witcher says in the program he will

take a lethal dose of drugs before the paralysis advances too far, he soon

finds himself helpless to do so and his physician and wife cannot help him

end his life. He had wanted to avoid the slow death and the suffering that

it brought to his wife.

Moyers said in a Yahoo! Internet chat the day the third installment aired

that Kevorkian, with the media's complicity, had framed the debate simplistically.

"Dr. Kevorkian asks: 'Are you for or against physician-assisted suicide.'

That's not the issue. The issue is: can you get good medical care at the end

of your life?"

Moyers told Current that he never considered having Kevorkian participate

in the series. "We were trying to do this differently; we weren't trying to

be 60 Minutes."

"I was trying to take the debate down to the most intimate terms..Real life

defies easy solutions. Death is such a personal, particular, intimate experience,

it's hard to make generalizations. We wanted to show real-life situations.

We were trying to say, 'Look at how difficult it is to wrestle with these

issues, but wrestle we must.'"

The companion web site (www.pbs.org/wnet/onourownterms)

contains a debate between two doctors for and against physician-assisted suicide,

as well as related subject matter.

—Geneva Collins

Web page originally posted Nov. 4, 2000

Current: the newspaper about public TV and radio

in the United States

Current Publishing Committee, Takoma Park, Md.

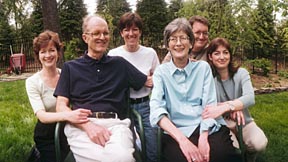

The project gives people an occasion to contemplate dying, and ways to make the best of it. A retired math teacher, Joyce Kerr (pictured with her family above) talked in the series about her plans to die at home. (Photo courtesy of the producers.)