Bob Edwards and satellite radio

Edwards’ jump to XM renews satellite debate

Already aloft: many other mainstays

of public radio

With Bob Edwards’ decision to leave NPR for a satellite radio company, public radio is debating again a highly ponderable question: Should it embrace satellite as a distributor for its programs or fear it as a competitor for listeners and revenue?

Edwards’ new weekday morning gig, The Bob Edwards Show, will start the morning for a new channel, XM Public Radio. The one-hour show will originate weekdays at 8 a.m. Eastern time and will repeat at 9 a.m.. The channel launches Sept. 1 [2004]; Edwards’ show debuts Oct. 4.

When NPR reporter Rick Karr broke the story of Edwards’ departure in July, he reported erroneously that Public Radio International was producing Edwards’ new show. Actually, XM will produce The Bob Edwards Show, but PRI-distributed programs will fill much of the rest of the channel, along with fare from Minnesota Public Radio’s American Public Media arm and Boston’s WBUR.

XM’s Channel 133 will feature some of pubradio’s most bankable shows, including This American Life and Studio 360, as well as hourly news briefs from BBC World Service. XM’s smaller competitor, Sirius, has aired three pubradio channels—NPR Talk, NPR Now and PRI Public Radio World—since its 2002 launch. NPR’s exclusive contract with Sirius, running through February 2007, notably excludes the big pubradio newsmagazines, Edwards’ old Morning Edition and All Things Considered.

For now, satellite providers play a relatively small role in radio. XM now has more than 2.1 million subscribers and Sirius just over 500,000, only a fraction of whom listen to pubradio programs since XM and Sirius each have over 120 channels.

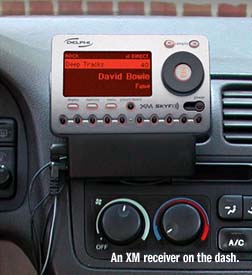

But media analysts estimate satellite radio will boast 10 million total subscribers by 2006 and XM sees an overall market potential of 20 million. It may be right: General Motors alone expects to install XM receivers in 1.1 million vehicles next year, according to XM.

No one can predict how satellite radio will fare, much less how it will

affect public radio, but there’s no shortage of opinions on the matter.

Pubcasters are split mostly among those who want to embrace the new platform

lest pubradio be left behind, and those loath to give away programming to

a potential competitor. Most believe stations should share in any wealth derived

from satellite broadcasts. And aside from revenue considerations, there’s

a question of whether pubradio’s public service mission demands that

it make its content available to the largest possible audience.

Put the flagships in orbit?

Even before XM’s Bob Edwards announcement, pubcasters were debating whether NPR should extend the audience of the newsmags by making them available on Sirius [Current article, June 21, 2004].

NPR initially withheld the flagship shows from Sirius at the behest of station managers hoping to protect their franchises, but some now think NPR should reconsider this policy. At this spring’s Public Radio Leadership Conference, Eric Nuzum, then director of programming and operations at WKSU-FM in Kent, Ohio, and soon to begin work as an NPR programmer, suggested that NPR put the newsmags on the satellite. He said not doing so meant withholding them from a population already equal to that of a sizeable city. Without the newsmags, NPR’s offerings on Sirius are like “a wheel without a hub,” he told Current.

The network has no plans to end the local stations’ exclusive hold on the newsmags, says NPR spokeswoman Jenny Lawhorn, though the network will commission a study this winter to explore, among other satellite-specific issues, whether omitting the newsmags is hurting NPR’s profile on Sirius.

NPR’s satellite policy grew out of a broader strategy, endorsed by its board in 1998, of seeking new distribution channels. For many station and network execs the plan was justified by fears that pubradio would be leapfrogged or sidelined in various new media in much the same way PBS lost standing during the cable explosion of the 1980s. Public TV concentrated resources on its single channel while competitors created dozens of cable networks.

A strict analogy to PBS’s woes doesn’t persuade Dick Kunkel, president of Spokane Public Radio. PBS wasn’t asked to put its strongest programs on a competing network, he says. PBS-member stations were carried intact on cable anyway. “If we should be learning anything from PBS and cable, we should be generating new programs for satellite,” he says, instead of giving pubradio’s strongest national programs to satellite competitors.

What’s at risk is the stations’ financial foundation and their ability to produce good local programming. “Our ability to do a good job on the city council depends on our fundraising from Morning Edition,” he told Current.

The comparison between satellite radio and cable TV also smells fishy to

Joe Lenski, executive v.p. of Edison Media Research. Though satellite is growing

in popularity, he says, it will not reach the 70 percent household saturation

rate of cable TV. He says 15 percent to 20 percent is more likely.

Rebuttals to the PBS/cable analogy may not persuade all pubradio leaders who

want to experiment in satellite radio. Many took the analogy as a general

warning that old media needs to dive into new media.

Public TV is a “sinking ship” and should not be emulated, pubradio audience analyst George Bailey told Current, expressing a view widely held in pubradio. “You want to swim as far away as possible.”

Sharing the theoretical wealth

Some station execs who support pub-radio’s excursions into satradio still question whether the terms are right. The Bob Edwards/XM deal suggests pubradio may be undervaluing its programs, says Mike Arnold, president of Public Radio Program Directors Association and p.d. of New Hampshire Public Radio.

“Public radio needs to do a better job of understanding the value of its assets,” Arnold told Current.

“If I’m not mistaken, Bob Edwards will make more money from satellite radio in his first year with XM than NPR has made in the entire history of its relationship with ... Sirius,” Arnold wrote in the Pubradio online discussion group this month. The names “public radio” and “NPR” are worth a lot, he wrote, and should not be sold short.

How much money will XM pay for Edwards and his new producers? The company isn’t talking, but the anchor earned $233,494 from NPR two years ago, according to NPR tax forms, and he told Current that his XM deal was worth “a little more” than what he made at NPR.

Arnold doesn’t oppose the satellite deals. New media, including websites, often pay little or nothing for valuable media content, he says, but program owners should be tougher in renegotiations and be ready to walk away from inadequate offers.

Doug Berman, e.p. of Car Talk and Wait, Wait. . . Don’t Tell Me! — both heard on Sirius — is among those who thinks pubradio should make its best programming available to satcasters. But he also thinks it should get something out of the deal. The system should broker some sort of revenue-sharing deal while the technology is still emerging, he says. “If it succeeds without us, we’re in a pretty weak position, but if we cooperate and it fails, stations don’t lose anything.”

One problem is that it will be hard to know if satellite radio is succeeding or failing. Knowing its audience size for pubradio programs would help producers know what fees to seek, but audience ratings aren’t available for either service, and ratings firms such as Arbitron won’t compile ratings unless someone pays for them, says Bailey. If neither service relies heavily on selling ads, they and advertisers will have little incentive to buy audience data.

The lack of ratings will handicap attempts to sell underwriting on satellite channels as well, Bailey observes. Alisa Miller, senior v.p. in charge of PRI’s Content Group, says American Public Radio LLC — PRI’s satellite partnership with Chicago Public Radio and Boston’s WGBH — hopes to woo underwriters with the opportunity to be in on “the start of something big.”

Miller says any new revenue produced by satellite will benefit stations by providing additional funds devoted to affiliate services, programming and development. NPR supports a more direct trickle-down theory of satellite economics, pledging to give stations half of its net revenue derived from satellite — if and when a surplus appears. Minnesota Public Radio spokeswoman Suzanne Perry says there are no plans to lower station programming fees as a result of any revenue gained from the XM agreement, noting that current fee rates don’t cover all programming costs.

XM spokesman George Butler said XM’s pubradio programming will include the producers’ underwriting messages and XM will sell additional sponsorship announcements. He wouldn’t discuss XM’s producer agreements.

All discussion of satellite riches are still purely theoretical, however — Berman notes that “nobody’s making money on this yet except for maybe Bob Edwards.”

But there may be ways to address stations’ concern that satellite-based pubradio programming will erode local fundraising. At the Public Radio Leadership Forum in May, Edison Media Research President Larry Rosin said access to satcasters’ pubradio channels could be restricted to subscribers who are also members of local stations. Sirius and XM have addressable-subscriber technology in place to achieve that — it already restricts access to premium channels such as Playboy Radio and High Voltage. Rosin was not available for comment at Current’s deadline.

The technology would also let satcasters beam pubradio shows to regions where they aren’t heard otherwise. Programs such as MPR’s new Pop Vultures, which has been airing on just a handful of earth-bound stations, will be available nationally on XMPR. Nashville’s City Paper said last week the XM broadcasts of Afropop Worldwide and American Routes are “cause for great celebration” because the shows are not aired by stations there.

The public service element might be the most compelling case for pubradio’s cooperation with satellite, but whether it ultimately persuades NPR to add the newsmags is anyone’s guess. Lawhorn says the results of the study will be ready by the end of 2004.

Web page posted Aug. 13, 2004

Current

The newspaper about public TV and radio

in the United States

Current Publishing Committee, Takoma Park, Md.

Copyright 2004