"Wandering through here was the saddest day of my life," said Feldman, recalling his return to WYES. He stands where office space was destroyed. (Photo: Karen Everhart, Current.)

"The Big Lurchy.” That’s David Freedman’s nickname for post-Katrina New Orleans.

The city is not so big anymore, and life in the famously laid-back metropolis certainly “ain’t easy,” said the g.m. of jazz/blues mainstay WWOZ-FM. “Everything you do is a struggle.”

Like other broadcasters whose stations were battered by the hurricane or flooded by mucky waters that followed, Freedman struggles daily to accomplish even the simplest things—delivering paperwork to an equipment supplier, getting an insurance form notarized, finding an auto shop to fix the flat on his car.

Public broadcasters in Louisiana have begun to talk about new ways of collaborating and expanding their services to the community, but those ideas are on the backburner for now. They’re all struggling to reestablish contact with their audiences and figure out a way back to normal.

“I think we should give something back to the community, but we’re too busy dealing with our own problems to really put it together,” said Chuck Miller, g.m. of WWNO, an NPR News and classical station.

“We’re really still in crisis mode,” said Mark Coudrain, g.m. of WLAE-TV, the smaller of the city’s two pubTV stations. “You operate day by day, week by week, month by month.” The station, established by the Archdiocese of New Orleans in 1984 and now controlled by Louisiana Public Broadcasting and a church-related support group, lost its transmitter to the floods in August and can be watched only on cable and the DirecTV satellite service.

WLAE heard from the Public Telecommunications Facilities Program that its request for federal aid has been approved, Coudrain said. But the station won’t have the money to restore broadcasting until its insurance claim comes through. He hopes to be back on the air in September.

The other pubTV station, community licensee WYES, resumed broadcasts Dec. 30 but lacks funding to make local programs.

While larger uncertainties loom over reconstruction and the city’s economic and cultural future, broadcasters make do with reduced cash flow and electricity, shrunken staffs and make-shift facilities. Any progress is incremental and can be lost the next day or in an hour.

“You want to move forward, but you can’t,” Coudrain said. “You never know whether the equipment will work.”

Public TV's stations were hit harder than public radio's. The storm and flooding damaged their buildings and equipment and threw a monkey wrench into their plans to relocate to a shared facility.

WYES and WLAE had planned to launch the public phase of their combined $4 million capital campaign last fall, said Randy Feldman, WYES president. The stations have $2.8 million in pledges for the campaign, including $2.1 million in the bank. But the big final push for contributions “fell by the way side because the phones and the mail service are so messed up,” he said.

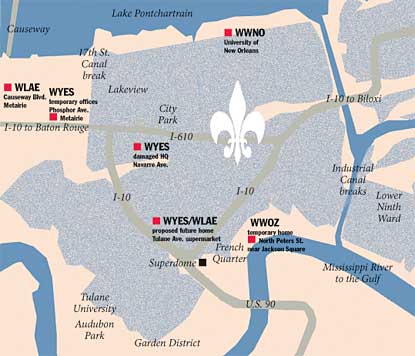

Shaded blue area shows approximate extent of flooding.

WWNO: limping at low power

“It’s really difficult living here,” said Miller of WWNO, a station licensed to the University of New Orleans at the north edge of town. “You can’t get away from it.” Miller began work at WWNO last July, arriving seven weeks before Katrina hit.

From WWNO’s office in the university library, Miller can see cranes at work on floodgates for the London Avenue canal and hear pile drivers loudly fortifying damaged flood walls before hurricane season begins in June.

WWNO was the first station back on the air in September, originating from Georgia Public Radio, Miller’s old employer, and beamed by satellite to New Orleans. The station’s production studios and offices weren’t flooded but lacked power for months after the flood soaked the university’s underground power cables.

The station’s biggest physical loss was its irreparably damaged transmission line. On-air talent returned to WWNO studios Dec. 19, but its back-up transmitter is operating at roughly one-tenth of the station’s 85,000 watts. “We lost service to about 10 miles of the fringe in our broadcast area,” said Ron Curtis, operations director.

Still, early responses from listeners have been strong. In two fundraisers since February, including a Valentine’s Day campaign, WWNO raised $324,000. “Core listeners really responded to how quickly we got back on the air,” said Miller. They also seem to appreciate the rip-and-read local news and public affairs announcements that WWNO added to its service, he says.

The revenue picture for WWNO is by no means rosy. “Underwriting is an issue,” Miller said. “We are down by half since we went back on the air in December.”

Emergency aid from CPB, dues waivers from NPR, PRI and other organizations and the university’s help in covering the payroll during the worst weeks helped WWNO avoid layoffs, Miller said. The other stations received aid from CPB and other pubcasters, but weren't able to avoid layoffs.

WWOZ: All’s fine on the surface

WWOZ, a community radio station connected with the city’s jazz and roots music traditions, resumed local broadcasts Dec. 12 from a temporary home in the French Market near the Mississippi River. The space is too small for ’OZ’s collection of 25,000 CDs, still housed at Louisiana Public Broadcasting in Baton Rouge. LPB provided studio space, technical assistance and grant-writing advice to WWOZ last fall, feeding the radio station’s programming into the stricken city for two months until WWOZ’s staff and volunteers could resume broadcasting back home.

Because the disaster struck at summer’s end — right when WWOZ was in the “low ebb of its cash-flow cycle” — Freedman laid off one staffer before Katrina. Its staff is down from nine to six.

“On the surface, we’re doing remarkably well, because we work with stuff that’s in a can,” Freedman said, referring to WWOZ’s music library. “The effect on our sound has been that we lost some of our sterling volunteer show hosts, who have such a wealth and breadth and knowledge and the collections to match.”

But these setbacks haven’t deterred supporters. WWOZ’s spring pledging raised more than $600,000 — half of the contributions came from online listeners outside the New Orleans area.

The response inspired Freedman to plan upgrades for online services and remote production capabilities that connect listeners to the city’s roots music scene.

None of that would be possible without help from other public broadcasters who assisted WWOZ during the “darkest days of our sojourn back from hell,” Freedman said.

Not only did LPB share its facilities in Baton Rouge, but WFMU-FM in Jersey City, N.J., temporarily hosted the WWOZ-in-Exile webstream during the first weeks after Katrina; CPB provided emergency grants; and the Development Exchange Inc. and Get Active contributed in-kind services and software permitting the station to raise money online. Some 29 pubradio stations appealed to their own listeners to support WWOZ, contributing $50,000.

With that donation from “the Katrina network,” as Freedman called the stations, WWOZ is buying a 26-foot production truck, he announced April 20 in a speech at the National Federation of Community Broadcasters Conference in Portland, Ore.

When the next hurricane hits—a likelihood feared by everyone in the city—Freedman plans to drive the truck to high ground and, with an old analog transmitter, resume broadcasts when the winds die down. When the truck is not needed at home, stations in the Katrina network can borrow it for their own remote broadcasts from music festivals.

Plans for the backup truck grew from Freedman’s disaffection for political leaders who failed to protect New Orleans from flooding and responded too late when it occurred. He worries about the mass evacuations of the city’s African-American neighborhoods, the state’s takeover of the city’s admittedly dysfunctional school system, the displacement of many of the people who make Mardi Gras a living tradition in the city. These and other changes in the city’s once-rich social fabric could kill its widely celebrated music and culture.

“The difference between a live and a dead culture is dead culture is for tourists and school books,” he said. “Live culture is everything that people express in the way they live—like in sewing the Mardi Gras Indian costumes.” This tradition, like the music curriculum and marching bands in public schools, carried the culture to successive generations, he said.

WLAE and WYES: Location, location, location

Of all the pubcasting stations in the Crescent City, public TV outlets WYES and WLAE face the most complicated path to recovery, their fates intertwined by their plan to move in together.

WLAE’s staff of 14 — downsized by a third since Katrina — is settling back into their offices in Metairie, west of the city boundary, along the road to the Lake Pontchartrain causeway. The building had to be gutted and its insides rebuilt after a tornado whipped up by Katrina ripped off the roof and water gushed into the building.

“This was to have been a temporary location six years ago,” Coudrain said, standing outside the production studio and master control. “When we get our insurance money for our equipment, we don’t want to put it here in this location,” he said.

WYES’s situation is just as bad or worse. Its staff is working out of three makeshift buildings, including the second floor of its flood-damaged facility on Navarre Street.

The TV stations shelved their original plan to relocate in a digital technology center at the University of New Orleans — for reasons no one wants to discuss in detail. Beth Courtney, executive director of LPB, said the overhead costs of the $19 million facility would have been too high.

It may be just as well. The proposed teleplex was on the east side of the university’s campus, which flooded after the hurricane, said Miller.

Of four sites considered by Feldman and Coudrain, their top pick is a vacant Albertsons supermarket near Interstate Rte. 10 on a stretch of Tulane Avenue with boarded-up hotels and storefronts. The 63,000-square-foot building, built in 2001, was flooded with one foot of water.

The space would be plenty big. WYES and WLAE need about 40,000 square feet for their shared master control, production studios and offices, according to Coudrain.

But the stations’ bid on the property was caught in another snare. A consortium of retail chains bought Albertsons Inc. in January and won’t decide on the sale until early summer, said Coudrain. “We’re looking at two other backup sites, but this remains our first choice.”

One alternative is overhauling the old WYES building, flooded when storm waters breached the 17th Street Canal. The first floor, with WYES offices, records, production studios and half of its tape archive, was ruined.

Flood plain maps that will guide New Orleans’ reconstruction and determine the price and availability of flood insurance indicate that Navarre Street occupants would have to raise the building by three feet. Feldman says the city, which leases the building to WYES for $1 a year, may be willing to negotiate on this point. It’s “still too soon to know,” he wrote in an e-mail.

“A tremendous build up of that kind makes it a last resort,” Coudrain said. LPB’s Courtney, who has influence on relocation plans as vice chairman of WLAE and as the official managing state funds to the pubcasting stations, has serious doubts about the Albertsons building.

She wants the stations to focus on delivering programs and services, not building big facilities, and would prefer a more central location that could be part of New Orleans’ redevelopment.

“I want us to a have vision for where we’re going in the future,” she told Current. “Let’s do something you know you can pay the overhead on.”

During a recent tour of the partially gutted Navarre Street building, Feldman recalled when he first returned to New Orleans in October. “Wandering through here was the saddest day of my life,” he said.

Also irreparably damaged were two key revenue sources for WYES: art and merchandise valued at $500,000 that had been donated for station auctions, and one of the two big mobile production trucks operated by WYES Productions, a for-profit business that provided at least a quarter of WYES’s $5.3 million pre-Katrina budget.

Like the radio stations, WYES recently received strong support from donors. Its March pledge totals were the station’s highest in three years, said Robin Cooper, development director. Unable to produce live pledge breaks, the station used packaged fundraising programs, but it did produce new spots to air around broadcasts of its popular local history docs. “There’s a new cry for anything that brings back memories and normalcy,” she said.

Member renewal appeals, the most stable source of viewer support, had to be mailed first class because the post office doesn’t accept bulk mail. Cooper and Feldman worry about how well direct mail will do, because local postal delivery is inconsistent at best. “We’re getting checks that were sent in December,” Cooper said.

Feldman estimates that the station’s post-Katrina budget will be 45 percent smaller, and late last year he had to eliminate 21 of the station’s 52 jobs. Some staffers chose not to return and others were laid off.

WYES has been able to afford one local production on the storm’s aftermath, “The Katrina Effect: Coping with Stress and Depression,” a studio-based special featuring Jeffrey Jay, a clinical psychologist specializing in post-traumatic stress disorder. The psychologist counseled Broadcast Director Beth Utterback last fall, and she developed the show after returning to live in New Orleans. “This was our way of trying to reach out and help the community,” she said.

Feldman recognizes that WYES needs to produce more, not less, local programs. “We have to be more than a broadcast channel to provide needed services to the region,” he said.

WLAE hasn’t mounted a pledge drive and, like WYES, depends on production-services business for revenues. “If it weren’t for our production business, I don’t know how we’d survive financially,” Coudrain says. “The phone system is barely working.”

To mount a new daily talk show program after the storm, WLAE turned to a funding method that puts business leaders on the air in exchange for donations. Tom Bagwill, a former reporter and anchor for a local commercial station, who worked on earlier WLAE client projects, lined up underwriting support for Greater New Orleans: The Road to Recovery.

“I called people I knew in business who had reasons to position themselves in the market,” Bagwill said, citing a tax attorney and a banker. Since its start in October, the show also has hosted officials from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Red Cross, mayoral candidates, other newsmakers and, in December, Elmo and Santa Claus.

The show costs $6,000 a month to produce but Bagwill hopes to stay on the air when the current batch of sponsorships run out. Post-Katrina New Orleans is a “very competitive advertising market and commercial stations are dropping their prices.”

To demonstrate what the stations are up against as they work day to day to restore services to New Orleans, station execs take a visitor through the city’s devastated neighborhoods. The places where their listeners, viewers and members lived—and the poor neighborhoods from which the city’s celebrated music sprung—are almost empty. Reconstruction appears to have stalled.

“A lot of people haven’t gutted their houses because they don’t know what will happen next hurricane season,” Feldman said. Roughly 480,000 people lived in New Orleans before the disaster and officials estimate less than half of the population has returned, he said.

In affluent Lakeview, every few blocks a contractor’s pick-up truck is parked in a driveway. FEMA trailers for residents are few and far between. Cars rest upended on the street, windows broken and tires missing. Brownish-yellow high water lines mark houses five to six feet from the ground.

WYES’s Utterbach used to live in one of these houses, now ruined. Regarding the disaster, she says to a visitor, “It’s bigger than people know, unless you’ve been here.”

Web page posted May 4, 2006

Current

The newspaper about public TV and radio

in the United States

Current Publishing Committee, Takoma Park, Md.

Copyright 2006