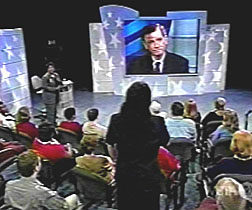

Atlanta citizens quiz surrogates for the two major candidates in a segment moderated by Gwen Ifill (left).

An eloquent campaign wrap-up from a virtual news division

Commentary originally published in Current, Dec. 4, 2000

By Jerry M. LandayOn Nov. 1 [2000], for the first time in three decades, the major domains of public broadcasting news and public affairs became the sum total of their parts. The results were exponential.

Producers of PBS’s NewsHour, working with their own reporters and an NPR reportorial team, and the intrepid doc-squad of Frontline jointly begat the three-hour pre-election simulcast A Time to Choose: A PBS/NPR Voter’s Guide to the Presidential Election. It was the single most impressive piece of political journalism on the air since the Murrow-Friendly team dusted off Joe McCarthy in 1954.

Time to Choose, a baedeker to the election, was a testament to public broadcasting’s purpose and potential. Robert Putnam of Harvard, a program participant, rightly commented that "campaigns are more and more not what we do but something we watch."

If that be true, then democracy’s future requires that we have access as a community to the literate, intelligent sound and sight of the likes of Time to Choose—early and often. It was a splendid alloy of resource by a virtual news and public affairs division that public broadcasting—and an impoverished electorate—so badly requires.

Given the Florida Sleigh Ride that followed, I wanted more of the same. In short, the broadcast’s very success begged the question of its infrequency on the public air when events demand it. This public-affairs joint venture must be the harbinger of the institution’s future.

Effective storytelling begins with sound structure, and the very simplicity of the Time to Choose format made it so eloquent and elegant. The producers from the NewsHour, Dan Werner and Michael Mossetig, well understood this. Their focus was the voters and the making of a Presidential choice. Ralph Nader’s critique notwithstanding, the theme was was the substantial distinctions of philosophy and substance between the two major candidates on pivotal issues. Virtually every element of the simulcast elaborated on that motif. The subtext in a scholarly closing discussion was the flawed character of the pandering campaign and a boom-happy electorate.

The production was a testament to informed editorial competence, sheer professionalism and cooperation. The result of its manifold platforms, connections and interactions—radio, television, and the Internet, thoughtful voters, exceptional producers and journalists, facilitators, campaign surrogates, scholarly analysts and commentators—was the restoration of a multilayered political conversation that has been assaulted and abstractified by hucksters, pollsters, partisan opportunists and a flood of money.

The basic outline of the program went like this: NPR correspondents Tom Gjelten, Julie Rovner and John Ydstie, as comfortable on camera as they are on mike, and the NewsHour’s Kwame Holman posited that there are differences between the major candidates, and then detailed them in theme-setting background pieces—the economy, health care, education and other pressing social business and foreign affairs. Articulate words were married to articulate graphics. Three sets of voters addressed comments and questions to each subject area. Based in Atlanta, Chicago and San Francisco, the "town meetings" were facilitated smartly by the NewsHour’s Gwen Ifill and Elizabeth Farnsworth, and WTTW’s Phil Ponce.

Surrogates for the candidates, hosted by Margaret Warner in Washington, provided their takes on each issue, and took questions directly from the voter panels. The interchange was brisk, cant and rhetoric minimal. Ray Suarez manned the Internet desk, weaving in trenchant comments and questions e-mailed from viewers. Elizabeth Arnold, NPR’s national political correspondent, contributed importantly on an expert panel hosted by NPR’s Juan Williams. For each section, Frontline producer Steve Talbot produced searching mini-docs with maxi-doses of meaning. Most praiseworthy: the piece on the candidates’ character, or lack of it, under fire.

With host Jim Lehrer moderating, commentators Tom Oliphant of the Boston Globe and David Brooks of the Weekly Standard capped each segment with penetrating acumen. They punditized without bloviating. Oliphant on Social Security: "The Bush campaign does a wonderful job of pretending to have a proposal . . . something of a piñata on the campaign trail." Brooks on Nader: "Some of that Nader vote is going to Gore. . . . It’s disappointing, because, as a conservative, I count on the left to commit suicide in the most self-righteous way possible."

Filigrees of frosting from NPR’s Alex Chadwick wrapped each hour. Behind a cardtable with the sign "Interviews 50¢," Chadwick enticed voters-on-the-street to a seat-of-the-pants vox pop at the Arkansas State Fair and at venues in San Francisco and Washington, D.C. Memorable gems:

- "I’ve gotta vote. It’s the only option I have to make anything better."

- Chadwick: "How old are you?" Lady: "Oh, you don’t ask no woman her age!"

- A Native American: "Time has taught my people over a thousand years that maybe government hasn’t got the greatest answer for everybody, but it’s the only answer that we have."

- Chadwick: "Who’s the most presidential person you can think of?" Man: "Bill Cosby. What this country needs is a dad . . . a funny guy who makes you sit down and eat your vegetables."

Amen. The grassroots atmospherics, as shot and edited, were superb.

All the threads of the electoral process were in place—ideas, discourse, sentiment, substance, showbiz, blarney and uncommitted voters whose articulateness chased cynicism away. Chosen by a Princeton, N.J., public opinion outfit, the citizens made substantive contributions to the structure with informed questions and interjections—a refreshing change from the visceral incoherence of shoot-from-the-hip network focus groups.

In fact, Time to Choose was well-appreciated liberation from the numbing clichés of standard-issue TV political coverage. We were relieved of reporters with unfolding news, the deterministic drone of poll numbers and true-believing analysts, the cookie-cutter punditorializing of a perennial cast of gasbags who focus on the holes and ignore the doughnuts, the "instancy" of post-debate "winners" and "losers," and the big-footing presence of a dominating "star." Jim Lehrer was perfect as dispassionate host in this PBS-NPR setting, compared to his bland-on-bland performance as interrogative debate host. On Time to Choose, reporters reported. A single contribution by a pollster, Andrew Kohut of the Pew Center for the People and the Press, was reserved for three minutes of the final hour. Sans the horse-racing, he quantified several illuminating dimensions of choice: the level of voter interest in candidates and process, and how issues and perceptions of leadership qualities were influencing decisions.

Nothing is perfect. The singular comfort level of NPR’s reporters on camera and mike raised the question of why journalists with something to say are so thoroughly "wallpapered" off the screen by a moving-image wall that often disconnects mind from substance. Notably absent were smaller-market communities, particularly in the "town meeting" and vox pop segments. This lapse cries for correction next time, if public-broadcast space is to mirror America.

The last two segments—a panel of author-scholars and a repetitive reprise by the voter-participants—could have been shortened to allow room for what this viewer calls Great Campaign Silences: in particular, Ralph Nader and the Greens, who were to stalemate the outcome. They deserved far more space than the gratuitous Nader sound bite we got. Several brief interjections on the Supreme Court were hardly enough. It reflects the classic journalistic omission of sidestepping the challenge of giving courts and the law the due that their importance merits (the likes of O.J. excepted). This segment could also have x-rayed tricky campaign rhetoric, such as George Bush’s code phrases "strict constructionists," and "affirmative access" instead of "action."

But practice makes perfect. Time to Choose as a tour de force confronts the leadership of NPR and PBS with the next challenging plateau. This creative brainchild of PBS President Pat Mitchell is a genesis.

"We need to continue providing civic space, with all our connections merged, that is uniquely public broadcasting," she said in a brief chat, adding that brainstorming sessions are underway on further elaborating the new public affairs partnership. "I can assure you," she said, "that’s the direction we’re moving in."

Jerry M. Landay, a writer on national issues, is associate professor emeritus in journalism at the University of Illinois, and served as a working journalist for Group W News, ABC News and CBS News. He co-produced the primetime documentary Profit the Earth for PBS and has recorded commentaries for NPR. He has been published in such journals as the Christian Science Monitor and USA Today.

. To Current's home page . Earlier news: For the special, PBS orchestrates collaboration among news organizations.

Web page posted Dec. 17, 2000

Current

The newspaper about public television and radio

in the United States

A service of Current Publishing Committee, Takoma Park, Md.

E-mail: webcurrent.org

301-270-7240

Copyright 2000